After Green Zone Protests, Can Iraq Be Salvaged?

Josh Siegel /

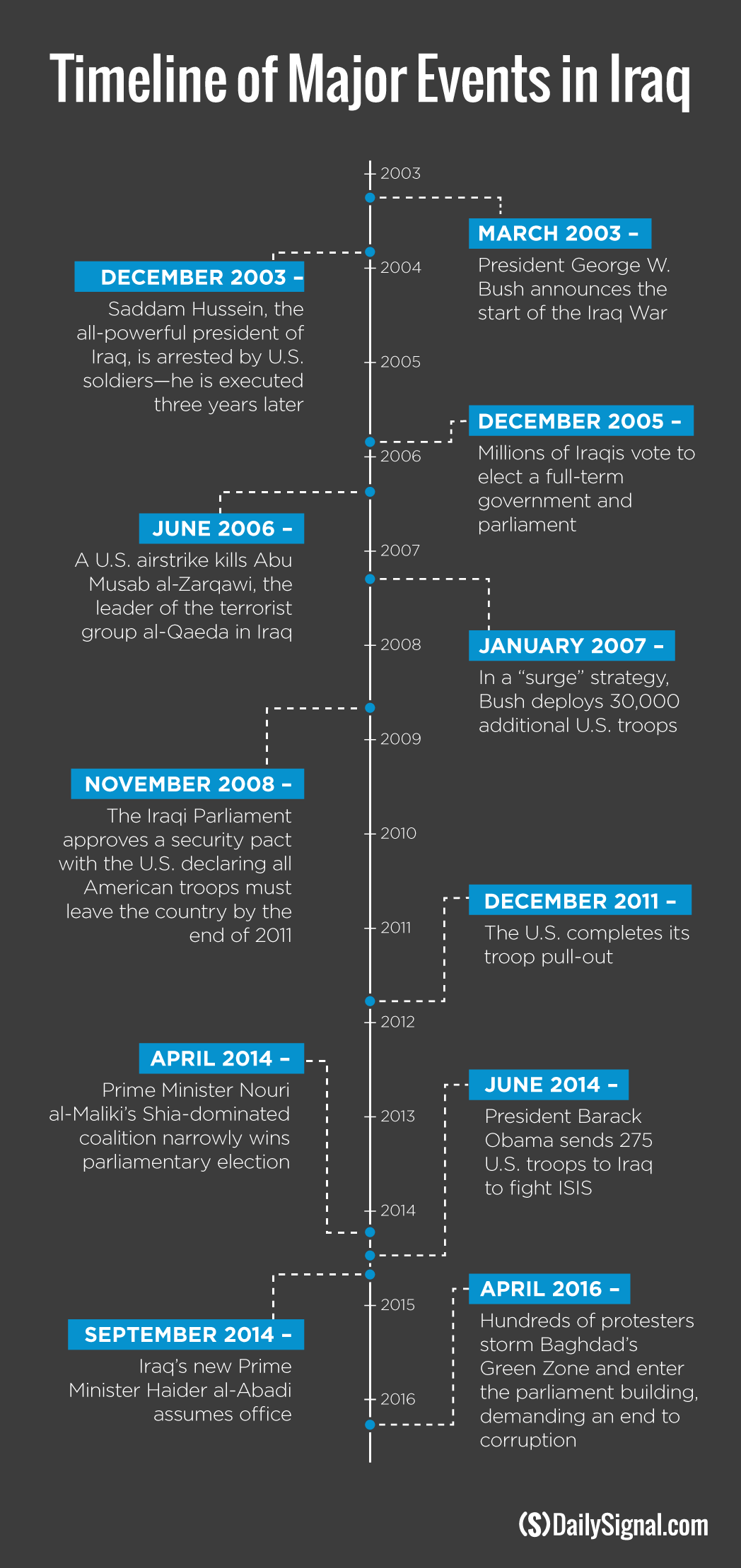

The scene of hundreds of protesters storming Baghdad’s U.S. installed “Green Zone” and parliament building this past weekend underscored the political challenges facing Iraq, and how the country’s internal turmoil must be resolved in order to defeat the Islamic State, or ISIS, terrorist group.

The protests, carried out by influential Shia Muslim cleric Moktada al-Sadr’s loyalists, were designed to push parliamentary opponents of Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, also a Shia, to approve a cabinet filled with technocrats rather than one dictated by party affiliation and religious sect.

In interviews with The Daily Signal, foreign policy experts who have spent time in Iraq, including a former U.S. ambassador to the country, say the protesters are likely to get what they want.

But that reform must be followed by a U.S. commitment to help the country unite, which the experts say is a necessity to take back the territory controlled by ISIS (roughly one-third of the country), and keep it out of the terrorists’ hands.

“Even though they are busy working on a military campaign against ISIS, the Americans have sort of lost focus on one-half of the challenge of Iraq—the political problems,” said Robert Ford, the U.S. ambassador to Syria from 2011 to 2014 who was the deputy ambassador to Iraq before that. Ford, who is now a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C, said:

There has been a lot of discussion about special operations forces, helicopters, and F-16s, but there has not been a lot of discussion about how how you get the Shia militias and the Kurds to settle differences. There’s been very little discussion about who is going to govern territory liberated by the United States. If you look at the places that have been liberated (about 40 percent of ISIS’ territory), these are not success stories. There is devastation, sectarian division and government corruption. You have a mess and the Islamic State feeds off of that—that is how they get more recruits.

Al-Abadi assumed office from former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, also Shia, with a promise of reform and inclusion. Maliki, who was prime minister at the time of the 2011 American withdrawal from Iraq, was known for authoritarianism and sectarian policies that disenfranchised the country’s Sunni minority.

Yet al-Abadi has faced challenges living up to his promises.

Two of the most effective fighting groups against ISIS in Iraq have been the Kurds, and Shiite militias, some of which have ties to Iran and have been accused of human rights abuses against Sunni civilians.

Iraq has also suffered from the collapse in world oil prices, and the country’s mostly one-dimensional economy has paid the consequences. Iraq’s government is struggling to provide basic services like electricity and health care to its citizens, including more than 3 million people who have been internally displaced by the war.

“Abadi is trying, but the storming of the Green Zone reflects a broader level of dissatisfaction and popular anger against the Iraqi governing elite, and it is an exacerbation of long-running complaints about government inefficiency and corruption, and the government’s inability to provide basic services the population expects,” said Nussaibah Younis, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Center for the Middle East.

As the director of a new Atlantic Council task force on the future of Iraq, Younis traveled to Baghdad in March to meet with al-Abadi, Massoud Barzani—the president of Iraqi Kurdistan—and everyday Iraqis, including both Shia and Sunnis.

She says if the Iraqi Parliament listens to the demands of protesters and approves a new cabinet of technocrats, it would help satisfy Sunnis who have felt marginalized since former strongman Saddam Hussein, who was Sunni, was deposed from power in 2003.

“Something you often hear from Iraqi Sunnis who are very angry from this current government is that, ‘We don’t care if it is Sunnis or Shiites in power—we would just like them to do a half-decent job, and to have a government that works,’” Younis said. “They are just sick of this government. This is not a sectarian issue. It is just a ‘you suck at governing’ issue.”

Even though the protesters are mostly Shia, their leader—al-Sadr, the Shia cleric—has forbid his followers from using sectarian chants, Younis said, and only permits them to raise the Iraqi flag.

Al-Sadr is a controversial figure who once commanded a militia that fought Americans after the Iraq invasion in 2003.

“Of course, Sadr has a very checkered history when it comes to sectarian violence, and a lot of Sunnis don’t buy his motivation for leading this protest movement, but what’s surprising is the number of Sunnis who do buy that,” Younis said. “Some Sunnis say he is a nationalist and anti-Iranian. They say Sadr is trying to reach out to Sunnis, recognizing the kind of reforms he’s advocating for affects all citizens equally.”

Renad Mansour, an Iraqi expert and fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center, agrees that Iraq’s government must respect Sunnis who are faced with the temptation of joining ISIS, which is Sunni-led.

“You don’t beat ISIS with guns, troops, or airstrikes,” said Mansour, who is based in Beirut, Lebanon, but spends much of his time in Iraq. “The way to do it is to reclaim legitimacy in the eyes of the disenfranchised people that are living under it. The Sunnis who are indifferent to ISIS can be won over if we present them with a better alternative. The removal of quota systems and sect-based politics—which benefits the Shia majority—would go a long way towards convincing Sunnis.”

James Jeffrey, a former U.S. ambassador to Iraq under the Obama administration, says he has spent a “lot of his time” trying to help Iraq’s leaders create better relations with Sunnis.

“It’s not a easy thing to do, having spent a lot of time trying to do it myself,” said Jeffrey, who is now a fellow at The Washington Institute. “They are very unhappy because they were running the place [Iraq] with 20 percent of the population and bang, we help Iraq institute a democracy, and by nature, if you are 20 percent, you are not the majority.”

In the face of Iraq’s turmoil, some are calling for the partitioning of Iraq into Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish zones. Vice President Joe Biden, who visited Baghdad last week, once famously proposed for the partitioning of the country in a 2006 essay. Jeffrey, like all of the other experts interiewed by The Daily Signal, does not believe separating Iraq is the right solution.

“They won’t stop fighting because there are three different countries,” Jeffrey said. “There are mixed populations. It’s one thing to be an Arab getting pretty good security because you live in Kurdish territory, but if you suddenly become an Arab living in a Kurdish country you won’t like that too much because your identity will be shattered and you are not sure you will get these services. There is no simple solution.”

Michael Knights, a fellow at The Washington Institute who has studied and spent time in Iraq since the 1990s, believes Iraq has the capacity to come together.

“I have seen these kind of crises numerous times,” Knights said. “Iraqis tend to take things right to the edge of the cliff before stepping back from the crisis. Iraq does have a sort of juggernaut quality to it. It can take a lot of damage and just keep going. It has a high pain tolerance. If you get a tradition of having more technocrats in the cabinet, and not goofballs, that’s a great thing. If you can fix the economy and make it more private-sector oriented and less focused on oil, that can be great thing for Iraq.”