The Hidden Tax That Costs Households Up to $1,600 a Year

Salim Furth /

A rising tide of regulation has covered almost a third of the U.S. labor market. Workers who previously could find a job on the strength of their experience and talent now need their state government’s permission before taking a job. The “permission slip” in this case is an occupational license or required certification.

Occupational licenses act as a barrier to potential new workers in an occupation. The costs and delay associated with obtaining a license convinces many potential workers to not even try.

As a result of the decreased competition among workers, customers end up paying more, either directly or through their state and local taxes.

Unequal Burden

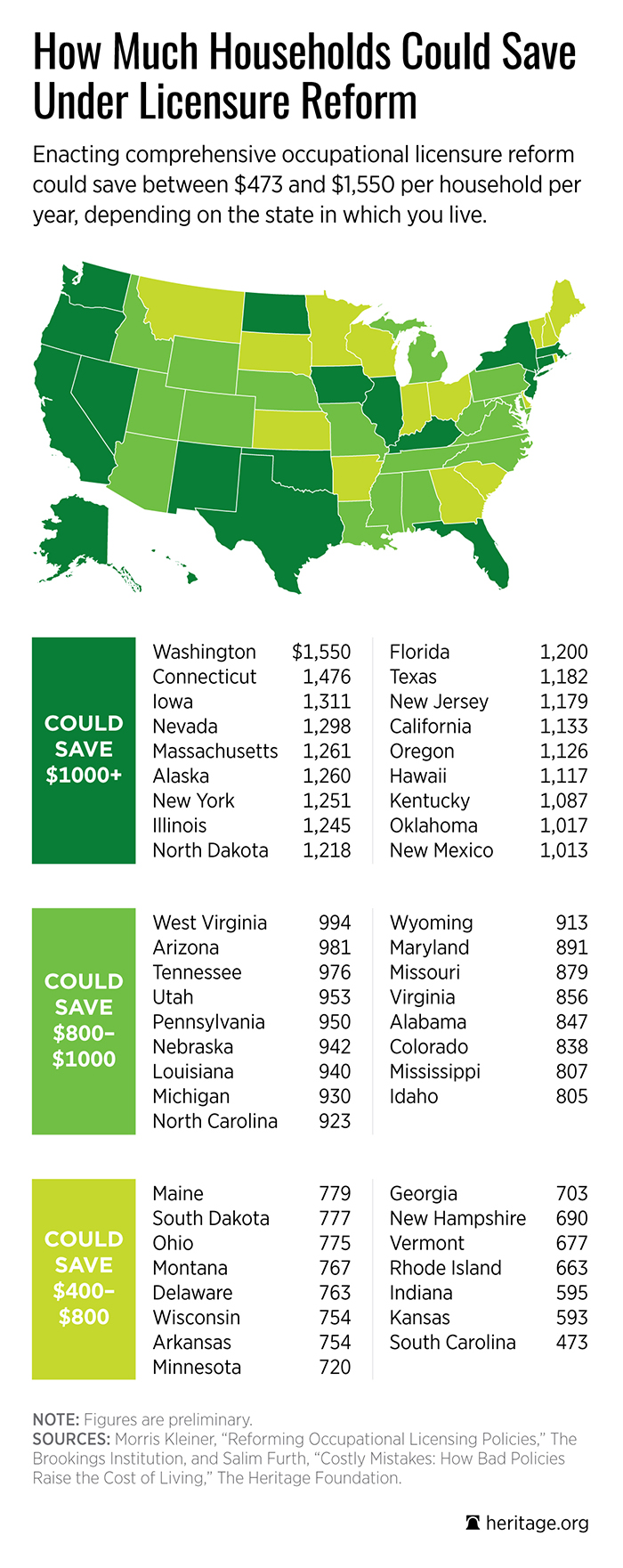

Although state-by-state licensure numbers are not firmly established, a Harris poll conducted in 2013 found large differences between the states. Applying the poll results to average annual earnings in each state and using $1,033 per household as a national baseline, I estimated how much the average household in each state would save from comprehensive licensure reform.

The hidden tax on services is highest in Washington and lowest in South Carolina. The six states that impose the highest costs are states where regulations and wages are both high: Washington, Connecticut, Iowa, Nevada, Massachusetts, and Alaska. In Washington, high regulation costs the average household $1,550 per year.

In low-regulation states the costs are much lower. South Carolina, Kansas, Indiana, Rhode Island, Vermont, and New Hampshire all impose less than $700 per year in hidden service taxes on the average household.

The results show that there are few obvious regional patterns in the data. For example, three of the six New England states are near the bottom of the list but two are near the top. Most Southern states have lower costs, but only because they have lower wages—and Florida and Texas are the 10th and 11th most costly in the nation despite moderate wages. Low-wage states have lower dollar costs, but readers should keep in mind that a hidden tax of $500 is a larger share of income for the average South Carolina household than it is for the average Washington household.

Every state has room for improvement—for example, South Carolina applies restrictive scope of practice rules to nurse practitioners. If the state instead followed the low-cost New England states and allowed nurse practitioners to prescribe medicine and practice independent of a physician, it would make health care more accessible and affordable without compromising on care.

Evidence

Typically, getting a license involves fees, tests, and continuing education. For example, to become a teacher in Illinois requires a $100 application fee, several tests (each of which has its own fee), and completion of a teacher-preparation class approved by the state. Prospective teachers must also have a bachelor’s degree.

To remain in good standing with the state, teachers have to pay $10 a year (and a $500 fine if they miss a year) and take continuing education classes. The simple certification, however, is not enough for an experienced teacher to become a reading specialist (requires a master’s degree) or to teach driver’s ed (requires specialized classes).

There are specific “endorsements” that are required for each age range—an experienced high school teacher cannot simply accept a job as a middle school teacher without first getting permission from the state.

There is little rigorous evidence that these licenses improve the quality or safety of the services being offered. The Council of Economic Advisers found 12 studies of quality and safety:

- Two of the 12 studies found positive outcomes from licensure;

- One found a negative outcome;

- Nine could not rule out licensure having no effect on quality or safety.

However, there is ample evidence that licensure increases the cost of services, makes it harder to find a job and harder to move between states.

Reform

Occasionally a state takes a step in the right direction, such as Nebraska’s legislature freeing hair braiders from the requirement to become licensed in cosmetology, which is unrelated to hair braiding. But no state has yet attempted comprehensive reform.

Any of the 50 states could step into this void by taking a bold step to help consumers and potential workers. One simple way to enact broad reform would be to recognize licenses granted by the other 49 states. Someone who is qualified to be a doctor in Wisconsin can practice medicine safely in Delaware. Honoring out-of-state licenses would help a state to attract skilled workers, boost its economy, and reduce the hidden tax on its consumers.