Federally Run Schools for Native American Children Are Worst in America. Here’s How to Fix That.

Lindsey Burke / Jacob Thackston /

Congress could soon find itself with a chance to radically improve the lives of thousands of children currently trapped in crumbling and failing schools now that Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., has proposed the Native American Educational Opportunity Act.

The proposal would enable children attending Bureau of Indian Education-funded schools to access education savings accounts to attend a private school of choice and to afford other education opportunities.

Funding for Bureau of Indian Education Schools is unique among K-12 education financing because it is almost entirely federal. Moreover, the Native American Education Improvement Act of 2001 makes clear that “the Federal Government has the sole responsibility for the operation and financial support of the Bureau of Indian Affairs funded school system.”

But even a quick look at that system reveals just how poorly the federal government has handled that responsibility.

The Bureau of Indian Education itself reports that only 53 percent of students who attend its schools graduate, well short of the national American Indian/Alaskan Native average of 69 percent, and shorter still of the total national average of 81 percent.

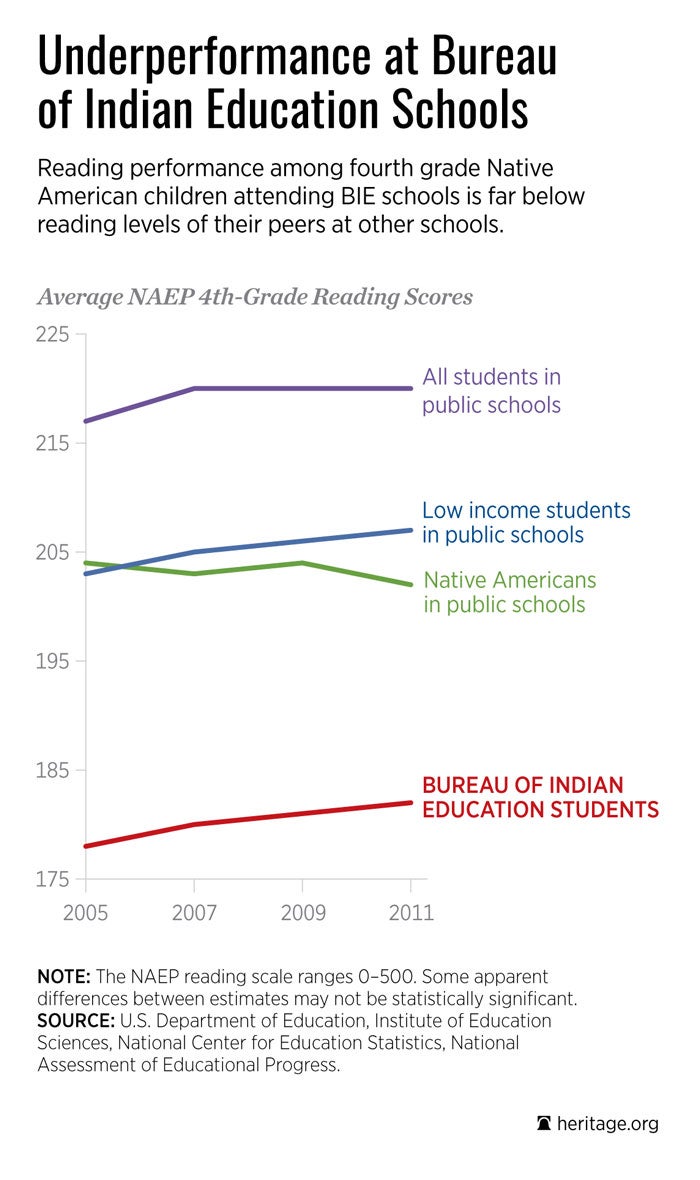

Further, the Bureau of Indian Education students scored, on average, 20 points—or roughly two grade levels—lower than their Native American peers attending public schools on the National Assessment of Education Progress fourth grade reading exam in 2011, the latest year for which Bureau of Indian Education data is available.

Sadly, the problems plaguing Bureau of Indian Education schools are not only academic. The Bureau of Indian Education system has massive and systemic problems.

A scathing Government Accountability Office report found:

… $13.8 million in unallowable spending at 24 schools as of July 2014. Further, in March 2014, an audit found that one school lost about $1.2 million in federal funds that were improperly transferred to an off-shore account.

None of this, it should be noted, comes as a shock to those who have paid attention to federal attempts to oversee Native American education over the years.

Politico wrote a searing exposé on schools run by the Bureau of Indian Education, entitled “How Washington Created Some of The Worst Schools in America.”

Reporter Maggie Severns notes that former education secretary Arne Duncan said the Bureau of Indian Education school system is “just the epitome of broken” and “just utterly bankrupt.”

The Native American Educational Opportunity Act would allow students who currently attend or are eligible to attend Bureau of Indian Education schools to access existing BIE funding in the form of education savings accounts in states that have them (which currently include Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, Nevada, and Tennessee, although Tennessee does not have any schools run by the Bureau of Indian Education).

What Are Education Savings Accounts?

Education savings accounts are parent-controlled spending accounts that are populated with funds that would have been spent on their child in a public school or, in this case, a school operated by the Bureau of Indian Education. Parents of eligible students could then use their education savings account funds to pay for private school tuition, online learning, special education services and therapies, curricula, textbooks, and a host of other education-related services, products, and providers. Unused funds could even be rolled over from year to year and could be rolled into a college savings account.

The federal government currently spends $830 million annually on Bureau of Indian Education schools and spends 56 percent more per student on children in these schools than average traditional public school expenditures.

Excluding boarding schools, the GAO reports that Bureau of Indian Education schools spent $16,394 per student during the 2009-2010 school year (inclusive of food service). Giving Native American families control over this funding through an education savings account model would provide a lifeline out of the failing school system. Unused education savings account funds could even be rolled over, and some states even allow those funds to be placed in a college savings account.

Instead of having a federally managed system of Bureau of Indian Education schools that not only fail in their duty to educate children, but also fail to employ basic and sound accounting practices, education savings accounts would empower some of the most underserved students in the country with choice in education, giving them new hope and opportunity for the future.