How a Suspected Murderer and Criminally Convicted Illegal Immigrant Avoided Deportation

Josh Siegel /

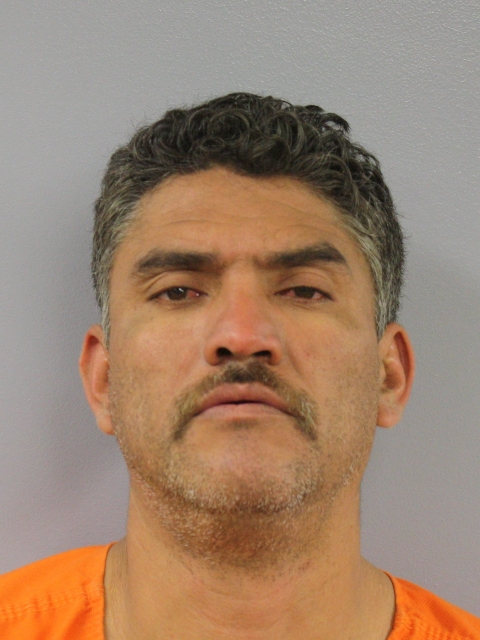

Before Pablo A. Serrano-Vitorino became the suspect in a murder spree across two states, the man, a once deported Mexican living in the United States illegally, was convicted of multiple crimes, across different agencies, but still free.

Serrano-Vitorino’s case involved a series of errors that kept him from being detained by federal immigration authorities, and from facing another deportation last year when he should have been removed from the country.

His case, experts say, showcases the precise communication required between local law enforcement agencies, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), in order to keep tabs on criminally convicted immigrants living in the country illegally—and how the slightest misstep could lead to tragedy.

“It should not be only ICE’s responsibility to make sure criminally-convicted aliens get on the path to deportation,” said Jessica Vaughan of the Center for Immigration Studies. “It is too big of a job. It sounds like there was an earlier opportunity for this guy to be in custody, and a combination of local agencies not stepping up to report him, and ICE missing the opportunity they had to deport him, gave this man the opportunity to commit these horrific crimes.”

Last week, Serrano-Vitorino, 40, was charged with four counts of first-degree murder for a shooting in Kansas City, Kan. Serrano-Vitorino was also charged with murder in the death of a fifth man in a separate shooting across the Kansas border in Missouri. After a manhunt, Serrano-Vitorino was arrested, and he is being held at Montgomery County Jail in Missouri.

In a statement to the media, Immigration and Customs Enforcement acknowledged that it should have detained Serrano-Vitorino before these incidents occurred.

Series of Errors

In September 2015, Serrano-Vitorino went to court in Overland Park, Kan., to pay a fine for driving without a license, for which he was charged with a misdemeanor and pleaded guilty, according to Officer Richard Breshears of the Overland Park Police Department.

He was fingerprinted at the court, and his criminal record was sufficient for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to submit a detainer requesting Serrano-Vitorino to be held.

But the federal immigration agency accidentally issued the detainer to Johnson County Sheriff’s Office, instead of the court, allowing Serrano-Vitorino to be released.

“Talking with our court, they had never received a detainer before he showed up in court or after,” Breshears told The Daily Signal. “In addition, our office was never aware of his status in this country because the courts never received a detainer.”

Breshears speculated that Immigration and Customs Enforcement may have mistakenly sent the detainer to the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office since it has a jail where Serrano-Vitorino would presumably be in custody.

The police department and the court, which are both in Johnson County but are under the jurisdiction of the City of Overland Park, do not have a jail.

An official with the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office, meanwhile, said they have no record of receiving a detainer for Serrano-Vitorino.

“We don’t know if someone sent a detainer because he wasn’t in our custody,” Deputy Claire Young told The Daily Signal. “He was never, ever in our custody so we don’t have documents or paperwork for him to even look back on.”

Long Criminal History

This was not the first time Serrano-Vitorino had come into contact with law enforcement in the U.S.

He first entered the country illegally in 1993, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement official told The Daily Signal. The official said Serrano-Vitorino was ordered deported in 2002.

The next year, the official said, Serrano-Vitorino was convicted in California of making a terrorist threat, a felony, and sentenced to two years in prison. He was deported in April 2004.

He illegally came to the U.S. again sometime afterward on an unknown date.

From there, in November 2014, Serrano-Vitorino emerged on law enforcement’s radar when he was convicted of a misdemeanor for driving under the influence in Coffey County, Kan.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement says it did not know that Serrano-Vitorino was in the country at the time and that the Coffey County Sheriff’s Office did not notify the federal agency that it had him in custody.

The Coffey Sheriff’s Office declined to comment for this story.

While some law enforcement agencies don’t always notify federal authorities of illegal immigrant cases that aren’t felonies, the Department of Homeland Security’s new rules governing detention and removal of illegal immigrants state that those convicted of a “significant misdemeanor,” which the agency says includes driving under the influence, should be a priority for deportation.

In November 2014, President Barack Obama, as part of his executive actions on immigration, issued a directive to end a controversial program called Secure Communities that required local law enforcement to hold illegal immigrants they arrested for deportation.

The program, created in 2008 under President George W. Bush and expanded by Obama, was criticized for punishing immigrants arrested of less serious crimes, like minor traffic violations.

Under the new policy, called the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP), federal immigration officials are directed to issue detainers for those in the country illegally who have been convicted of serious offenses or those who pose a risk to national security.

In addition, the new program mandates that Immigration and Customs Enforcement no longer ask law enforcement agencies to hold somebody in custody to be picked up for deportation beyond the period when they would normally be released.

Instead, local authorities are supposed to notify Immigration and Customs Enforcement only when they plan to release someone federal officials have requested information on.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, however, can still issue a detainer if they believe they have probable cause to deport an illegal immigrant who has been arrested, even if they haven’t been convicted.

Serrano-Vitorino, meanwhile, was arrested again last June on a domestic battery charge in Wyandotte County in Kansas.

According to an official from the Wyandotte County Sheriff’s Office, per its internal procedure dealing with anybody it arrests who is born outside the U.S., the agency notified Immigration and Customs Enforcement that it had Serrano-Vitorino in custody.

Lieutenant Kelli Bailiff of the sheriff’s office said the agency gives federal immigration authorities four hours to respond about whether they want more information on the person in custody.

Because Immigration and Customs Enforcement did not respond in that time frame, Serrano-Vitorino was released, Bailiff said. The official from Immigration and Customs Enforcement told The Daily Signal that they could not verify Serrano-Vitorino’s identity because he was released from custody before the federal agency could take action. The New York Times reported that Immigrations and Customs Enforcement never received Serrano-Vitorino’s fingerprints.

The Priority Enforcement Program, like Secure Communities before it, requires law enforcement agencies to submit fingerprints to the FBI for criminal background checks. That information is then sent to Immigration and Customs Enforcement so federal officials can determine if the person is a priority for removal.

Bailiff said her agency followed that directive, as it always does for anybody it books.

She speculated that maybe Immigration and Customs Enforcement didn’t get the results of the FBI check until after the four hour response window expired—and Serrano-Vitorino was already released.

Bailiff said Wyandotte County would have provided fingerprints directly to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement if they had asked for it.

“Normally, what happens is, if they are interested in a person, they send a query and maybe call us, or they may send someone to interview that person or ask for more information like fingerprints,” Bailiff said. “We wait for direction from them, and they did not respond at all.”

Bailiff said that the situation may have been made more confusing because Serrano-Vitorino did not provide his full name to Wyandotte County. He identified himself as Pablo Serrano, she said.

“The information is only as good as what we are provided from the person we are booking,” Bailiff said. “If the person lies to us, we send ICE the info the person gave us.”

Who’s to Blame?

No matter who’s to blame, Republicans in Congress and critics of federal immigration policy are looking for answers on Serrano-Vitorino’s case.

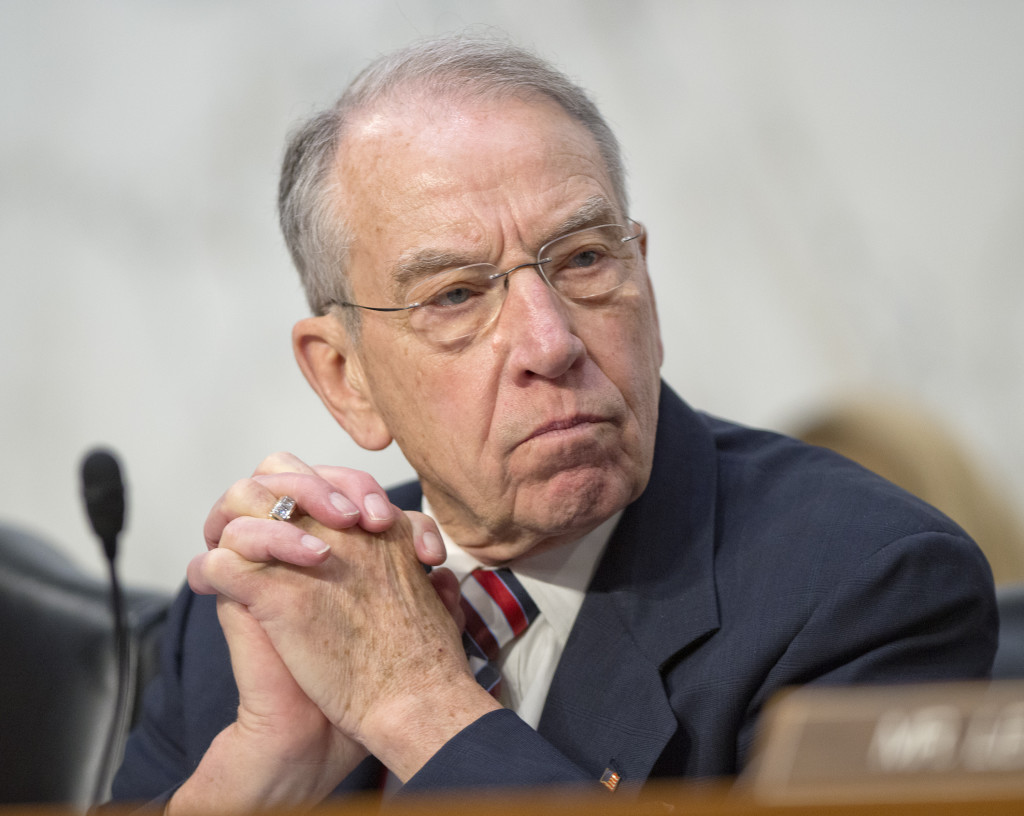

On Monday, Rep. Bob Goodlatte of Virginia and Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the chairs of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, wrote a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson asking for “a more thorough understanding of how this violent offender evaded immigration authorities and removal from the United States.”

Sen. Chuck Grassley (pictured), R-Iowa, along with Rep. Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., sent a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson seeking answers on how a criminally convicted illegal immigrant avoided deportation. (Photo: Ron Sachs/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Specifically, they ask if Serrano-Vitorino should have been a priority for removal under the Obama administration’s new Priority Enforcement Program.

“I think ultimately the responsibility in this case is with ICE because they sent the [September 2015] detainer to the wrong place, but I think this is a lesson for all local law enforcement agencies that they need to be on the ball because they are the ones who end up picking up the pieces when more crimes are committed,” said Vaughan of the Center for Immigration Studies.

Bailiff of the Wyandotte County Sheriff’s Office defended her agency’s relationship with federal immigration authorities.

“We have a good relationship with ICE, and it’s not unusual for them to call us and ask for more information or send someone right away,” Bailiff said. “They do respond many times to our queries.”

Alex Nowrasteh, an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, believes the mistakes around Serrano-Vitorino’s case do not reflect a problem with policy, but rather were a function of a bureaucratic failure.

“It’s really a lot of administrative snafus combined,” Nowrasteh told The Daily Signal. “It’s not like there’s a policy to release these people on the local level, and clearly not at the federal level. It just sounds like a complex bureaucratic screw-up made possible by an overly complicated system.”