She Had an Abortion at 15. How It Changed Her Life.

Kelsey Bolar /

Nona Ellington was 15 years old when she found out she was pregnant. A victim of rape, Ellington felt alone, ashamed, and desperate for help.

After a free pregnancy test came back positive, showing that Ellington was five weeks pregnant, she went forward and scheduled an abortion.

Around October 1983, Ellington, who was still in high school at the time, aborted the only child she would ever successfully conceive.

“As a result of that [abortion], I was never able to have children,” Ellington told The Daily Signal. “I had five miscarriages, two were pregnancies that required emergency surgery, and [during] the last one in 2004, the only tube I had left ruptured, so I was bleeding internally, and they almost lost me.”

When Ellington was eventually ready to have children with her then-husband, she said she visited a fertility doctor who “confirmed that it was the abortion that had damaged me so much that I was not able to have children.”

Ellington considered trying in vitro fertilization (IVF)—where an embryo is manually transferred into the uterus—but said even if it would work, her health insurance didn’t cover the cost.

“It covered abortion. But not fertility stuff,” Ellington said.

Looking back on her experience, Ellington calls abortion the most “selfish” decision she ever made, and now she spends her time trying to warn other women against it.

As part of that effort, Ellington joined 3,348 women who shared their abortion “injury” stories with the U.S. Supreme Court as part of what’s called an amicus curiae brief.

Their hope is that by discussing their “injuries”—both physical and mental—the Supreme Court justices will uphold a controversial Texas law that places new regulations on the abortion industry.

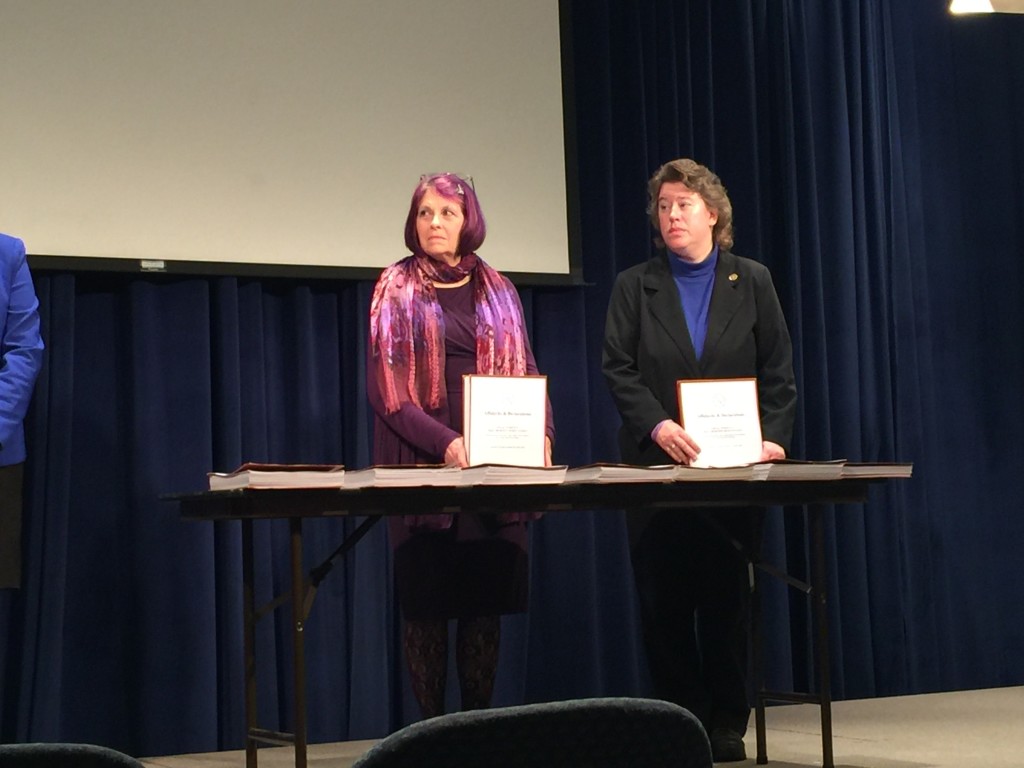

Myra Jean Myers (left) and Nona Ellington (right) share their abortion stories in a brief filed before the U.S. Supreme Court for the case Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt.

The case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, is being called one of the biggest abortion cases since Roe. v Wade, in which the Supreme Court said that women have a right to abortion while also affirming a state’s right to regulate the practice.

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt could signal how far states are allowed to go in issuing those regulations.

The law in question, known as H.B.2, requires abortion facilities in Texas to maintain the same standards as ambulatory surgery centers and abortion doctors to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals.

Whole Woman’s Health and its supporters believe that the imposed regulations dangerously limit women’s access to safe and legal abortion.

“Abortion is one of the safest medical procedures performed in the United States, and neither of the requirements imposed by the Texas law would make it any safer,” the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said in a statement. “Worse, this law clearly imposes an undue burden on a large number of Texan women, who would no longer have reasonable access to abortion care when needed, forcing them to wait longer before an abortion, travel across state lines for safe care, or even forego abortion care altogether.”

Those in favor of upholding the law argue that the regulations are “commonsense” for the health and safety of women.

The law, wrote Sarah Torre, a pro-life expert at The Heritage Foundation, “was passed in response to the conviction of late-term abortionist Kermit Gosnell, who ran a ‘House of Horrors’ abortion clinic for over a decade with nearly no government oversight.” She added:

After the Gosnell grand jury recommended new clinic regulations and after hearings on the medical risks of abortion, Texas (along with other states) decided to require abortion clinics to meet the same minimum cleanliness and safety standards as other outpatient surgery facilities and require doctors performing abortions to have the credentials to admit a patient to a nearby hospital.

Myra Jean Myers, another plaintiff on the Supreme Court brief, said she’s experienced some of these dangers firsthand. Both Myers and Ellington spoke last week at a press conference held at the Family Research Institute one day before the court heard oral arguments for the case.

“Abortion is a dangerous procedure,” Myers said. After her procedure, Myers said, “I had a hysterectomy two months later.”

A hysterectomy is a surgery to remove a woman’s uterus. At 28 years old, Myers, too, would never be able to conceive again due to her abortion.

Myra Jean Myers, pictured above, said her husband pressured her into getting an abortion, believing “the lie that it’s not a child yet. “

Allen E. Parker, a lawyer at The Justice Foundation, which is the non-profit submitting the personal testimony by women who allege injuries caused by abortion, said most of the participants “suffered grievous psychological injuries,” “but many suffered severe physical complications as well.”

The most common physical complications of abortion, he added, are hemorrhaging, punctured uterus, punctured colons, and scarring of the uterus.

“In abortion, you’re basically scraping the walls of the uterus and the contents of the uterus with a scalpel-like instrument,” he said. “And you’re doing it by hand in most instances, or by feel, the doctors would say. And you can punch the wrong part, and that’s where the complications occur.”

As for the mental conditions, Parker cited guilt, shame, sadness, depression, anxiety, drug abuse, and suicide as the most common conditions.

Ellington blames her abortion for causing her to “spiral” into a “very destructive behavior of drugs, alcohol, and promiscuous sex.”

Myers said that while the physical scars are still present, it’s the mental anguish that continues to haunt her.

“Nothing wounds you like being responsible for the death of your child,” she said at the press conference.

Parker, who sounded hopeful that the Supreme Court will consider the testimony of the 3,348 women when issuing their ruling in the case, added, “Whether you’re for abortion or against it, you can acknowledge that some women are hurt by abortion, and we ought to do everything we can to protect these women.”

This article has been updated to correct a fact about Nona Ellington. The original article referred to a court document that was about a different Nona Ellington.