The Truth About Low-Wage Jobs and Robots

Salim Furth /

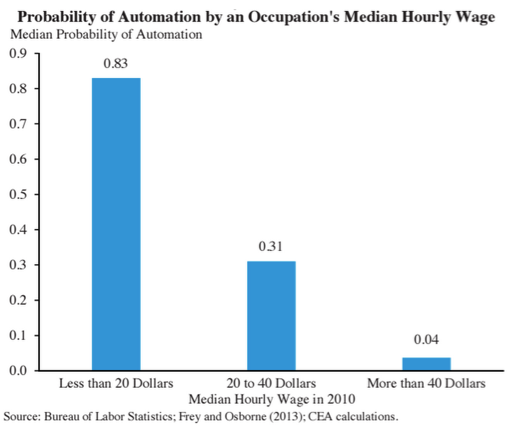

The Economic Report of the President reports that low-wage jobs in America have an 83-percent chance of being automated. Before you tell your supervisor to take that cash register and shove it, however, it should be noted that the automation of most jobs is not going to occur any time soon.

Before you tell your supervisor to take that cash register and shove it, however, it should be noted that the automation of most jobs is not going to occur any time soon.

The chances of your job being automated during your lifetime are much lower than the percentages reported by the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA).

What’s more likely is that some of the tasks you do in your current job will be automated, and the emphasis of your job will change a bit, in the same way that jobs have been changing for the past three centuries. As Heritage researchers James Sherk and Lindsey Burke found, there is little evidence that automation is occurring more rapidly now than in previous decades.

Guesses In, Garbage Out

The automation chances published by the Council of Economic Advisers originate from an interesting—but ultimately speculative—paper by Oxford University scholars Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne. The authors categorized 70 professions they thought have either a 100-percent chance of eventually being automated or a 0-percent chance. Since they didn’t identify professions that have already been automated away, the original classification is speculative.

It is probably true that loan officers are more likely to be replaced by computers than preschool teachers, but by giving loan officer jobs a 100-percent chance of eventually being computerized, the authors begged the question. If they had more modestly said that loan officers had a 50-percent chance of being replaced with computers, their overall results would have changed radically.

Frey’s and Osborne’s research can be thought of as usefully ranking occupations from most to least likely to be automated. (For the record, out of 702 occupations, they found that telemarketers are the most likely to be replaced by computers and recreational therapists least likely.) However, the percentages attached to different occupations and categories are guesses.

Tasks May Change, Rather Than Jobs

A less obvious problem with applying Frey’s and Osborne’s research to real life is that occupations are not fixed groups of tasks. From the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, the tasks that constitute a job have evolved to take advantage of the available technology. Medical professionals, for example, are among the least likely to find their jobs automated. But the tasks involved in medicine constantly change as new treatments emerge and computerized diagnostics replace conventional methods. A doctor or nurse who struggles to interface with computers may find himself out of work even if his job is not “automated.”

From the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, the tasks that constitute a job have evolved to take advantage of the available technology.

Just because a robot can take your job doesn’t mean it will. Robots are lazy, after all, and really prefer backgammon and cigars to an honest day’s work. Robots are also—no kidding—expensive, especially when they require sensory equipment to interact with the world around them. A teenage cashier can sense when a customer is unhappy, see a shoplifter, or walk out to the parking lot to clean up debris. Those are extremely difficult tasks for a robot.

Thus, although it is easier to automate lower-wage jobs, as the Council of Economic Advisers notes, employers will do so only if the machine is cheaper and better than keeping employees. Legislation that tries to force compensation higher, such as minimum wages and mandatory benefits, makes it more likely that employers will be forced to automate jobs.

Lost Jobs

While you might know a person named “Coleman,” odds are you don’t know someone who makes his living as a charcoal burner. Modern society has plenty of experience with automation and large-scale job destruction. Usually it takes place slowly. Historically, most of the jobs that have been automated away have involved the kind of backbreaking labor that left our ancestors twisted and hunched by their 50s. The U.S. and other economies have gone through several such transitions without ever having a period of mass technological unemployment.

It is no stretch to predict that some common current occupations will go the way of the cooper. Some might be mourned, but most are likely to be the jobs that are currently considered mundane or dangerous. But the same historical precedents say that the economy, without government guidance or intervention, has always found good uses for willing workers, almost always in jobs that are more productive and better paid than what was lost.