Nearly 500,000 Foreigners Overstayed Their Visas Last Year. What That Means.

Josh Siegel /

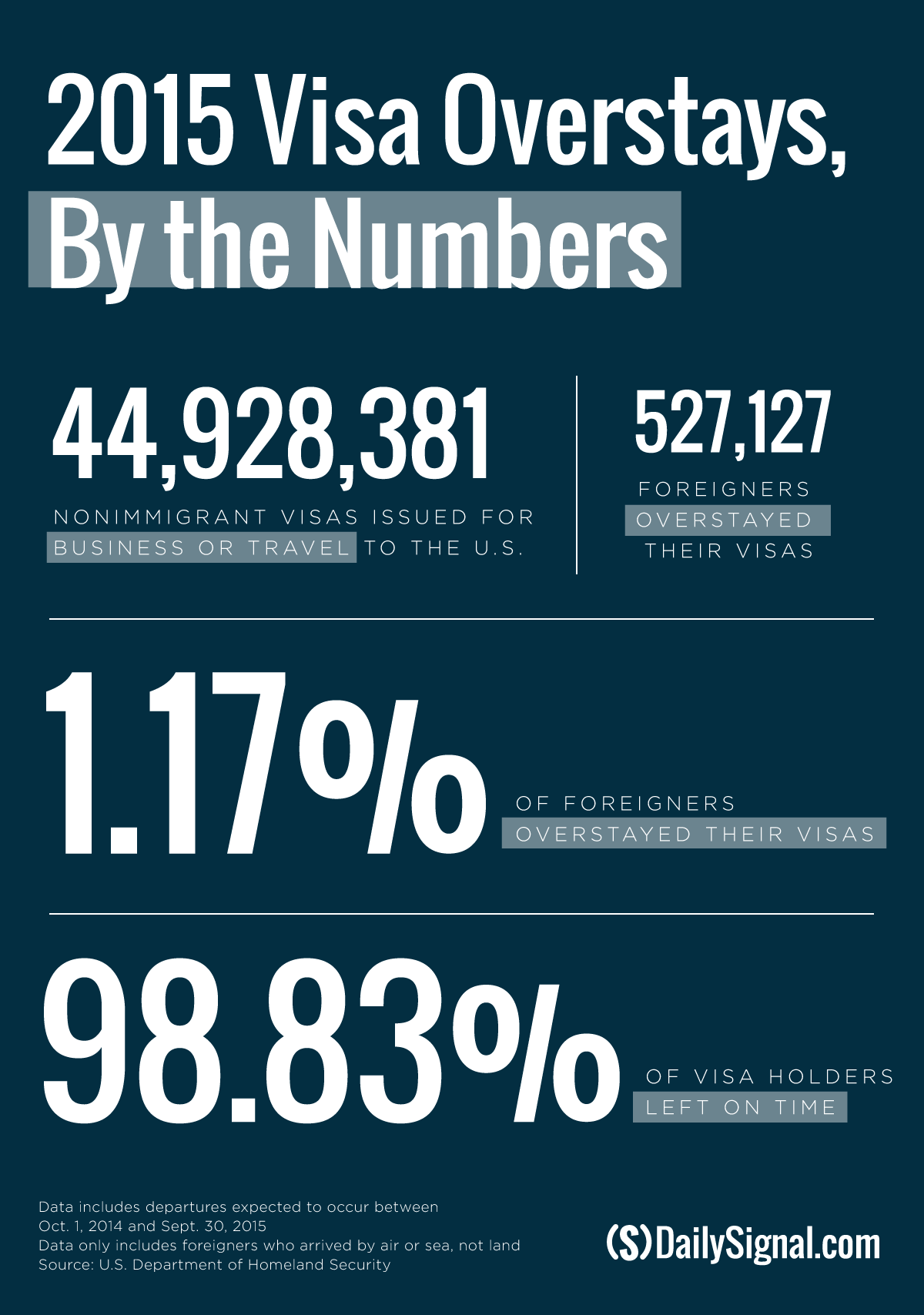

Almost 500,000 foreigners who traveled legally to the U.S. last year for business or leisure remained here after their visas expired, according to a long-awaited government study on one of the more undertold aspects of the country’s immigration story.

The Department of Homeland Security report, first requested by Congress in 1997, shows that 1.07 percent of the nearly 45 million foreigners who entered the country legally in 2015 overstayed their visas.

The report is limited in that it contains information only from travelers using certain visas and does not include data on others, like those coming here as students or temporary workers. It also includes information only on people who arrived by air or sea, and not foreigners who came by land.

Indeed, while experts warn of drawing conclusions from the report, since it includes only one year of data and can’t be compared to anything, the numbers relating to visa overstays —a population that represents an estimated 40 percent of the roughly 11 million immigrants living in the country illegally—will likely add to the nation’s tense debate over immigration.

“This is an area where Congress for 20 years has been asking for this information, and now we have a roadmap to determine what’s the best way to improve these numbers,” said Stewart Verdery, a senior Homeland Security official during George W. Bush’s administration, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

After receiving the report they sought, members of Congress expressed frustration at a weakness in the system described by the report: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, an agency of Homeland Security, does not have the ability to obtain biometric data—such as fingerprints, facial recognition, and iris scans—on people leaving the country.

“If we do not track and enforce departures, then we have open borders. It’s as simple as that,” said Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., who questioned Homeland Security officials at a hearing Wednesday put on by the Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest. “There is no border at all if don’t enforce our visa rules.”

Sen. Jeff Sessions says the government must improve its entry-exit system of tracking people who arrive and leave the U.S. on visas. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

The study sheds light on Homeland Security’s ongoing challenge to build an “entry-exit” system that can accurately track all people coming into and leaving the country.

Foreigners who apply to enter the U.S. on a visa are interviewed and photographed and have their fingerprints taken at a consulate overseas before arriving there. But collecting biometric data on those exiting the country is not as easy.

That’s because U.S. airports do not have exclusive areas for domestic and international flights, which makes it hard for Customs officers to screen out overseas travelers and get their information.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been undergoing tests to obtain biometric exit data, including one that began last year where officers use mobile devices to collect fingerprints from passengers at the departure gate. In addition, John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City debuted facial-recognition technology this week.

Verdery, who worked on the entry and exit system at Homeland Security, said the challenge is finding a cost-effective method that does not inconvenience travelers.

“The question is, where do you collect the information? At the jetway? Via a kiosk after security? During the security check? At the airline counter?” Verdery said. “Where do you put them that doesn’t inconvenience travelers and is actually effective in making sure someone has left? None of the options are particularly great. And though the biometric equipment is very mature, there is also a manpower issue.”

At the Senate hearing, Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said he expected Homeland Security to come up with solutions after lawmakers, he said, provided $2 billion in a government spending bill this year for the exit-entry system.

“Knowing who is going in and coming out is a matter of national security, plain and simple,” Schumer said.

Similarly, Jessica Vaughan of the Center for Immigration Studies wonders how the government has not solidified its entry-exit system so many years after the 9/11 Commission recommended it as a tool against terrorism.

“The implementation on a better exit tracking system is more a lack of will than a lack of viable solutions,” Vaughan said. “It’s not something that can happen over night, but we can definitely do it. The problem is this is an unguarded gate, and it shows how our legal immigration system is being abused.”

Even if the government was better able to get better exit data, experts say, there would still be challenges to enforcing the law against those who have overstayed their visas.

“Even if you had a more precise entry-exit system and even if you are able to capture the exit information on everybody, that does not lead automatically to being able to conquer the problem of overstays,” said Doris Meissner, who leads the U.S. Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute. “Because though the data tells you who’s left and who’s remained, you don’t know where those people are.”

Foreigners who enter the U.S. on visas do have to say where they are going, but there’s no stopping them from traveling elsewhere when they enter the country.

So the question for immigration enforcement officials becomes whether it makes sense to expend resources on finding people who have overstayed tourist or business visas, when those foreigners have already been screened before coming here.

“The question becomes how much of a problem from a standpoint of enforcement are these people as compared to people you know have committed a criminal act and are able to trace because they are being released from jails where they served their sentences,” Meissner said. “By definition, people here on visas are here as tourists, or they are visiting family or coming to a concert or cultural event. They are part of international mobility. So there has to be a real commonsense element to how you use data like these for enforcement purposes and what makes sense from a cost-effective standpoint.”

Verdery believes that the government can do more to deter visa overstays, by better notifying foreigners when they have been in the country too long and reminding them of the consequences of not leaving on time.

According to federal statute, foreigners who overstay their visas by 180 to 365 days before leaving cannot enter the U.S. again for three years.

Those who stayed more than a year too long can’t come here again for a decade.

The hope among experts is that having baseline overstay numbers provides the government incentive to improve.

“The Coast Guard is not expected to stop 99 percent of drugs, and the FBI is not expected to stop 99 percent of crime,” Verdery said. “I think Customs and Border Protection’s view is that 99 percent [of people not overstaying their visas] is a great start, but where can we find improvement knowing at some point you will reach a law of diminishing returns?”