What the Gift of a Gun for Christmas Taught a 9-Year-Old Boy

Michael Graham /

Say what you want about the conservative, churchgoing Grahams of Lexington County, S.C., but we knew how to cut loose for Christmas. Growing up in the Deep South, I never had the pleasure of a white one, of course. But what we southerners lack in snowfall, we make up for in lard. And sugar. And gravy. Usually in the same dish.

My father is a lifelong fiscal conservative (aka “cheapskate”), yet Christmas was the one time of year he would crack open his wallet. Though he bragged about being “tighter than Dick’s hat band”—a vaguely disquieting southernism that has something to do with frugality—my sister and I awoke to a mountain of presents every Christmas morning.

And I do mean morning. As evangelical Christians, we celebrated Christ’s birth in the early hours of daylight, as the Good Lord intended. People who celebrate Christmas on the eve are either utterly unfamiliar with biblical teaching or Catholic. (I kid, my papist friends.)

For us, Christmas morning always exceeded expectations. The breakfast of spicy Bisquick sausage balls and “mimosas” made with sparkling grape juice never disappointed. Even the music was from Christmas Central Casting. For reasons still unclear to me, gas stations used to give away Christmas albums produced by Firestone and Goodyear (nothing says Christmas like a lube, oil, and a filter). These were all-star collections of Andy, Bing, Burl, and the gang. Mom would stack them on the record player and—assuming the arm of the record changer didn’t get stuck—we’d have a nonstop soundtrack for Christmas morning.

My mom’s philosophy on Christmas present distribution might be called the “Chicago voting” model: early and often.

Do I even need to say that we had a real tree? Of course we did. And not some scruffy pine from the woods behind our house, either. (“Too redneck!”—my mom.) No, sir, Dad would splurge on a Fraser fir bought from the Rotary Club. Did he do it because it sent my sister and me into paroxysms of Christmas glee? Or because it gave him an excuse to screw around with digit-endangering power tools late into the night? Only Santa knows.

I do know that the tree filled our small, 1970s prefab home with an opulent scent of celebration. When I was young, I thought every fancy cocktail party I saw in the movies must smell the way my house did on Christmas. My mom would add to the overall effect with potpourri and stacks of presents around the tree. Her philosophy on Christmas present distribution might be called the “Chicago voting” model: early and often. Just days after the tree went up, we already had significant giftage growing. By Christmas Eve it looked like a dump truck from Macy’s had crashed into our living room.

I remember one Christmas morning in particular. I was 9 years old, and we were having a banner day. My sister and I were exhausted from the sheer volume of presents. Shards of wrapping paper were scattered like shrapnel on the North African desert after Rommel had rolled through. We were just transitioning from the “heartfelt gratitude” portion of the program to the “Hey, that’s mine” ceremonial combat when my dad asked, “Are you sure that’s it?”

I looked under the tree. Nothing. I scanned the post-Christmas carnage. Not an unwrapped package in sight. I glanced at my mom, who was also looking around the room with a “Did I forget something in the attic?” look on her face.

(The fact that I never heard my parents rummaging around the crawlspace over my room late on Christmas Eve is proof that Santa is real.)

Then Dad nodded his head toward the upright piano along the wall. “Look over there,” he said.

I waded through the wrapping paper, peered behind the piano and saw . . . something. A long, leather case leaning against the wall. I dragged it over to our floral-print sofa and laid it on the cheap, olive-green carpet at my father’s feet. “Open it up,” my dad said, a twinkle in his notoriously nontwinkling eyes. There was a zipper at one end. I slid it down, reached in, and pulled out something long and heavy.

“Oh, Simon!” my mother cried.

No, it wasn’t a Red Ryder BB gun. (This was years before “A Christmas Story.”) It was a single-barrel, break action, 20-gauge shotgun. A real live gun.

There aren’t actually words for what I felt in that moment. I was astonished, flabbergasted, stupefied, and more. Of course I hadn’t asked Santa for a shotgun. I hadn’t asked him for a Lamborghini or a date with Princess Leia either, because certain things are simply beyond a boy’s imagination. My shotgun wasn’t a crazy, extravagant Christmas present. It was an impossible one. And yet here I was, holding it in my hand, as my father beamed with satisfaction.

And that’s when it got me. The thrill of hope.

I have very few other specific memories of my childhood Christmases after that. What I do remember are vague feelings of disappointment. It’s not that my Christmases were less bright. They were the high point of my year. But when a child is convinced that Christmas is the season when impossible hopes come true, then he can only be disappointed. For no matter how glorious the gifts beneath the tree are, he has the human capacity to hope for even more.

Christmas is an irrational celebration of the limitlessness of our hopes. And yet, that’s why the disappointment we inevitably feel isn’t a bug. It’s a feature. Unrealized hope is always there to tempt us away from the joy of what we have, the good things already grasped in our hands. Which is why every child has, at least once in his life, cried on Christmas morning.

Now that I’m a father, I’m doing my best to keep my childhood traditions alive: A real tree, spicy sausage balls, and children bursting out of their bedrooms on Christmas morning like joyous, uncaged beasts.

But my favorite moment comes the night before, in the waning hours of Christmas Eve. The children are asleep. The fading fire still burns, though darkly. Music drifts softly through the house (the same Goodyear Christmas soundtrack), and the tree stands in the red-tinged darkness, warm with lights.

I’ve got a drink in one hand, and the other draped over the shoulder of my wife, lying drowsily on the sofa next to me. The warm, heavy scent of the tree fills my lungs and unleashes my memories—memories of my children on Christmases past, along with fresh smiles over how giddy they’ll be in the morning when they see all the wishes Santa made true.

Christmas is an irrational celebration of the limitlessness of our hopes.

I have hopes for my children, these four precious gifts I have been given by grace, though these hopes may seem modest to you. Other parents may fantasize about a family of Nobel Prize winners who star in Oscar-nominated movies in their spare time. Me? I just want them to be healthy, to be happy, and to avoid a few of the painful mistakes I’ve made. A future without sorrow or want. Is that too much for a father to hope for?

I think of my wife, nestled beside me so warm and vulnerable. Dare I hope she loves me even half as much as I love her? She doesn’t talk about it often, but my wife has multiple sclerosis. Every day she wages a solitary battle against her own body, and she does it without complaint. And if that’s not bad enough, she has to live with me—a husband who works in radio and writes on the side, an enthusiastic, but often inept, partner. How does she do it? Why must she? Can’t she just live, without another day of worrying about bills, or struggling with her health, or being let down by her oaf of a husband?

Those days are coming, I know they are. But as I sit beside the tree, so still, so quiet in the light of the fading fire, that knowledge fades, too. I’m drawn away by my own impossible Christmas gift. By the elemental power of a simple story, whose symbols are all around me: A star. A manger. A baby, born so helpless, so alone. And yet somehow, so full of hope.

I don’t notice it, but my eyes are moist. My throat is dry. And there in the pale light of the glistening tree, hope envelops me like swaddling clothes. It warms me like the breath of a newborn child. It fills my lungs. It pumps the very blood through my heart. I close my eyes. I bow my head.

And I believe.

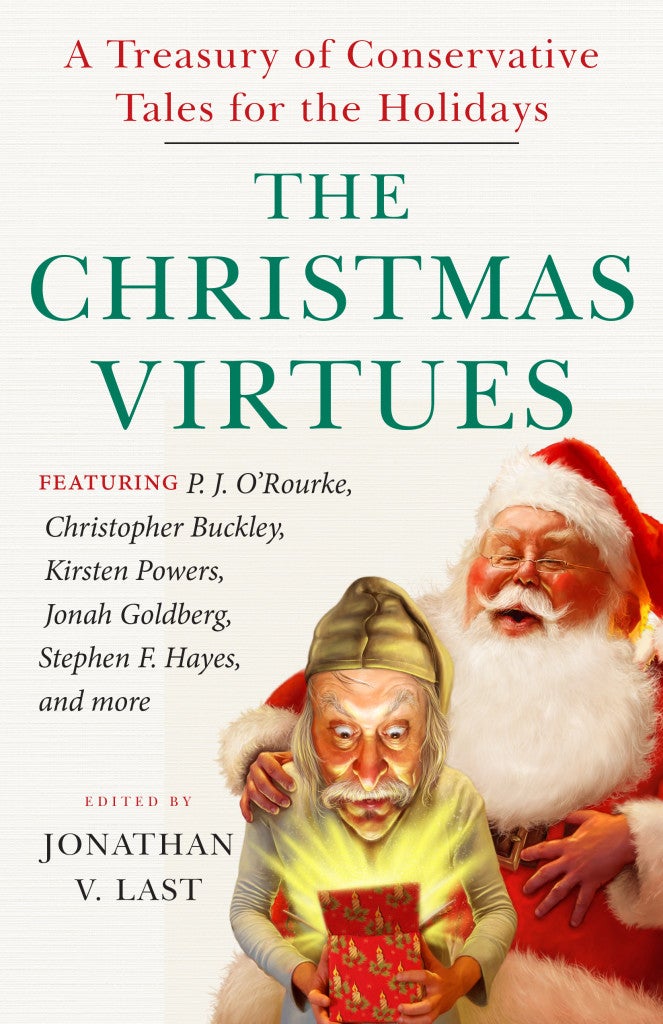

This is an excerpt from “The Christmas Virtues: A Treasury of Conservative Tales for the Holidays.“