Most Senior Citizens Haven’t Fully Paid for Their Medicare, Social Security Benefits

Robert Moffit /

Have senior citizens really “paid for” the Medicare and Social Security benefits they enjoy in retirement? Many believe so. But for the vast majority, the answer is – unequivocally- No.

Federal entitlement payroll taxes and general revenues finance Medicare and Social Security benefits on a “pay–as-you-go” basis, meaning today’s workers’ taxes fund today’s retirees. Workers’ taxes are not deposited in anything like a private sector “trust fund” today and “saved” for tomorrow’s benefits.

>>> Read the full report: Reducing Taxpayer Subsidies to Wealthy Medicare Recipients Is Sound Policy

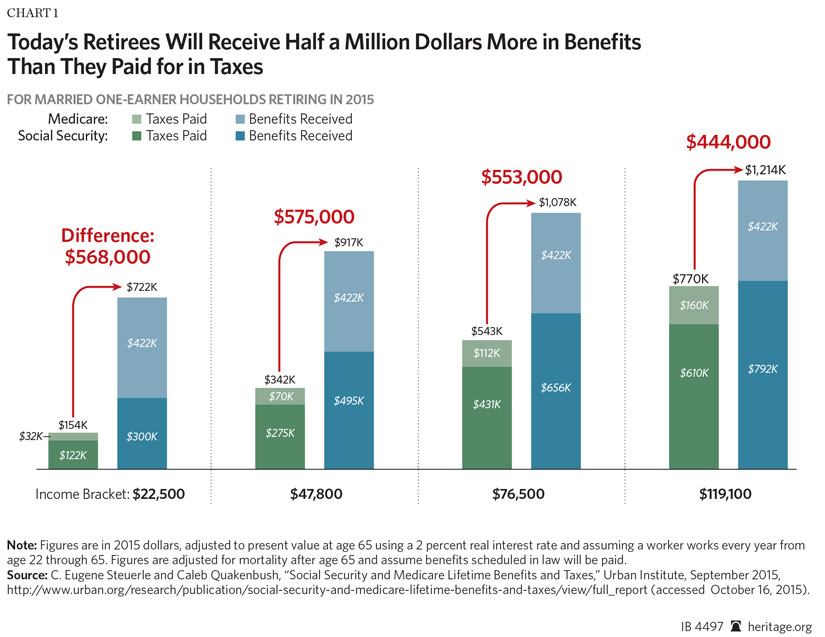

In fact, many senior citizens receive more in benefits than they paid in taxes. Analyzing the Medicare and Social Security data, Urban Institute researchers estimate that a married couple in a single earner household, retiring in 2015 – and earning an average annual income ($47,800 in today’s dollars) – will have paid an estimated $683,000 in lifetime Medicare and Social Security taxes, but will secure $1,038,000 in lifetime benefits in retirement.

But, as the chart below shows, that payment and benefit pattern applies to retirees in a variety of annual income brackets-ranging from households in the lowest income bracket ($22,500) to those in a fairly high income bracket ($119,100).

Big Taxpayer Challenge

Medicare today presents the biggest fiscal challenge for current and future taxpayers. Medicare Part A (hospitalization) is mandatory, and, not surprisingly, younger workers’ payroll taxes often fund retirees who are financially better off than they are. Enrollment in Medicare Part B (covering physician’s services) and Part D (drug coverage) is voluntary; no one is forced to enroll in these programs and pay Medicare premiums.

Even so, by law, Medicare beneficiaries generally only pay 25 percent of their premiums. Taxpayers directly subsidize the remaining 75 percent out of general revenues from the Treasury. A mere 6 percent of Medicare’s population, namely high-income recipients, pays higher premiums.

Yet, even with this formidable taxpayer funding, Medicare is generating an enormous unfunded obligation (over the next 75 years) of between $28 and $37 trillion. That jaw-dropping dollar amount represents the promises made to Medicare beneficiaries that are not financed by payroll taxes or dedicated revenues.

Unless Washington changes course, young working families are faced with enormous future tax increases, or Medicare recipients are in for some savage benefit cuts, or some ugly combination of both.

A Small Step

Tax and provider payment policies can only go so far in “fixing” Medicare. The right remedy is a comprehensive Medicare reform based on an expansion of defined-contribution (“premium support’) financing, stimulating cost-cutting competition and the widest possible consumer choice of plans and providers.

Short of that, Congress can take small steps to reduce taxpayers’ burden, such as increasing the number of wealthy retirees who pay higher premiums. Rep. Fred Upton, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, would require Medicare beneficiaries with an annual income in excess of $1 million to pay 100 percent of their Part B and Part D premiums.

That’s not a bad start, but Congress should go further and increase the number of wealthy Medicare recipients paying higher Part B and D premiums from roughly 6 percent to 10 percent of the total Medicare population. A little common sense, a dash of equity, and some planning for the country’s fiscal future would be a welcome break from business as usual and a good first step to comprehensive Medicare reform.