How Federal Missteps Make the Case to Transfer Public Lands to States, Localities

Marjorie Haun /

A forest fire on national parkland in Washington state in 2014 overtook a young black bear, seriously burning its front paws. This little bear, which would gain world renown, crawled on its elbows out of the massive Carlton Complex fire on land managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Later named Cinder, the malnourished and horribly burned bear was rescued and treated by wildlife officials and volunteers.

After months of medical care and physical rehabilitation, officials last June released Cinder into the federally managed Black Bear Rehabilitation Center near Boise, Idaho.

Cinder was one of the lucky ones. Millions of animals of all kinds, including privately owned livestock, have been burned and killed in massive wildfires on federal lands in recent years.

With forests overgrown and piling up with underbrush and dead and dying trees, some would argue that releasing Cinder into a federal preserve carried a degree of risk to the tough little bear. Federal “no-logging” policies, it seems, are turning America’s national forests into kindling.

A growing number of state organizations seek to remedy what they consider negligent policies and shoddy oversight of public land on the part of federal agencies.

>>> How Much Land Near You Does the Federal Government Control? This Map Tells You

Under the umbrella name “Transfer of Public Lands,” the movement offers a solution to the problem that is simple in concept: transfer ownership and management of public lands administered by federal agencies to equivalent state agencies. These agencies, being accountable to governors, state legislators and citizens, will manage the public lands in a more conscientious, cost-effective way.

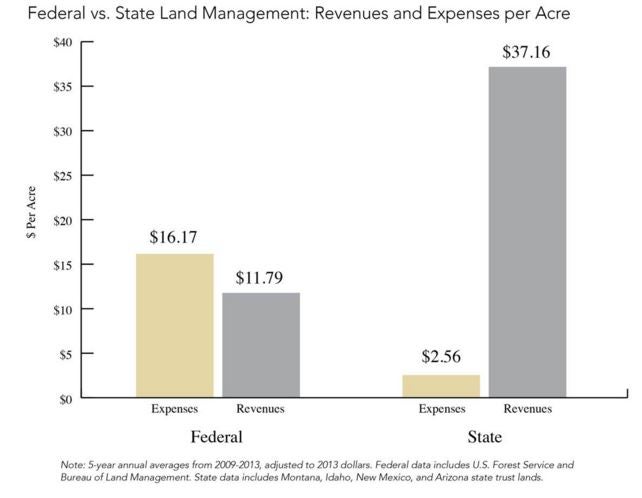

According to a report by the Property and Environment Research Center, a think tank focused on property rights, federal management results in a net loss of revenue but state management produces a net gain.

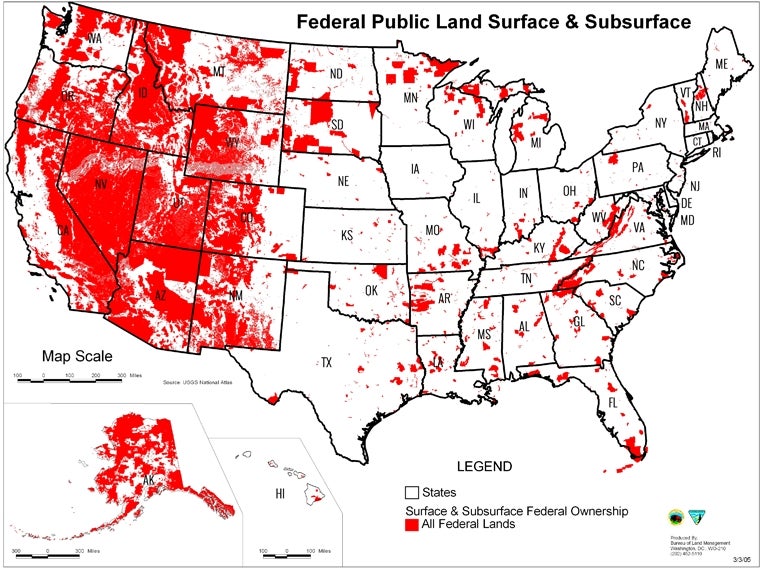

Unlike states east of the Continental Divide, public lands in Western states such as Washington and Idaho predominantly are owned by the federal government. They are under the management of the Interior Department and a plethora of subagencies, including the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

This map from the Bureau of Land Management illustrates the imbalance between West and East when it comes to how much land is under federal control:

A Growing Movement

Utah is at the forefront of the Transfer of Public Lands movement. In 2012, the Utah state legislature passed legislation that lays down the foundation for transferring public lands to state ownership.

National parks, national monuments, tribal lands and Defense Department property are excluded from the transfer. Called the “Transfer of Public Lands Act and Related Study,” it was signed into law by Gov. Richard Herbert, a Republican.

The American Lands Council has been tireless in making the legal and moral case for transferring public lands in the West to the states.

“Public lands stay public,” says Ken Ivory, council spokesman, “and our national treasures will be well protected and preserved.”

In late October, The Los Angeles Times published an article noting that seven Republican candidates for president had expressed support for devolving federal jurisdiction to the Western states.

Bungling, overreach and overreactions by the federal government may make the strongest case of all. Within such instances of federal mismanagement are stories of human suffering and environmental degradation.

In November 2008, Rose Backhaus, a 54-year-old Colorado woman, was hiking in Utah’s federally managed Little Wild Horse Canyon. She became lost in the canyon when she took a wrong turn on the trail. She likely wandered for days, eventually succumbing to exposure. Her body was found by hikers the following April.

The local office of the Bureau of Land Management, which is responsible for the property, had received requests from locals for years to place a sign in the canyon directing hikers to the proper trail. The federal agency failed to act, arguing that such a sign would be too expensive and have an adverse impact on the “wilderness experience.”

More recently, a woman in Josephine County, Ore., feared for her life as her ex-boyfriend broke into her home. She called 911 and was told there was no one available to help her because of budget cuts. The local sheriff’s office, lacking the resources to pay deputies and staff, failed to respond to the woman’s pleas. Although the dispatcher remained on the phone with the woman, the intruder later sexually assaulted her.

Josephine County was built on the logging industry. When the federal government began to implement policies to “protect habitats” for threatened or endangered species in the Northwest, the timber industry imploded. Federal timber funds dried up. Broke and beleaguered, the sheriff’s office experienced firsthand the economic effects of misguided federal policies.

Two Cases of Overkill

In September 2014, The Los Angeles Times ran a feature story, “A Sting in the Desert,” detailing a case of massive overreaction by the Bureau of Land Management in Southeastern Utah.

A respected family man, civic leader and local physician named Jim Redd was under scrutiny by agents with the land agency and the FBI on suspicion that he looted nearby American Indian archaeological sites and traded artifacts on the black market.

The Times reported that a paid, undercover informant working for the land agency and FBI, equipped with a “button” surveillance camera, spent hundreds of hours in Dr. Redd’s home, perusing artifacts his family had collected for generations.

The informant, identified as Ted Gardiner, was seeking evidence that would link Redd to the illegal antiquities trade. Eventually Dr. Redd’s wife, Jeannie, gave in to Gardiner’s insistence by selling him a pair of yucca sandals. With that transaction supplying the evidence they wanted, the land agency and FBI launched a massive, military-style raid on the Redd home.

The Times reported that dozens of armed agents dressed in body armor arrived in a convoy of SUVs and arrested Dr. Redd, 60, at gunpoint, handcuffed him and marched him into his garage where they taunted and interrogated him for hours.

Dr. Redd and his wife were charged with numerous felony counts and both faced decades in federal prison. The day after the raid, Dr. Redd took his own life.

Following the suicide, Gardiner shot and killed himself, witnesses said, in remorse over the raid leading to Redd’s death.

Even if Dr. Redd were guilty, why did these federal agencies react with such massive force to raid the home of a beloved small town doctor who had no history of violence?

In another case, father-and-son Oregon ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond were convicted of arson and sentenced in October to five years in federal prison for setting fires that burned 140 acres owned by the Bureau of Land Management.

A former Forest Service agent had testified on behalf of the Hammonds, saying: “The Hammond family is not arsonists. They are number one, top-notch. They know their land management.”

The prosecution of the Hammonds under an antiterrorism law is another disquieting example of federal overreaction to a relatively minor crime.

At times, though, federal management decisions simply defy reason.

This past summer, while massive wildfires shot across regions of Montana, the Forest Service—under the direction of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack—restricted the state from using its fleet of helicopters to suppress the fire without justification or explanation.

Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, a Democrat, declared a state of emergency and authorized the National Guard to use its resources to aid fire-fighting efforts. But under federal management, the state’s firefighting fleet of Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters remained grounded.

One Size Fits All?

Citizens and leaders in the West understandably are frustrated and angry with federal overlords.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s devastating—and preventable—spill of millions of gallons of toxic mine waste into Colorado’s Animas River made national news in August. To many, the incident was illustrative of the need for local and state control over managing natural resources and preserving the environment.

Ivory, the spokesman for the American Lands Council, describes the problem this way:

The one-size-fits-all bureaucratic ‘solution’ is really the problem. Wildfires resulting from overgrown and diseased forests in the West burn millions of acres every year. We all want clean air, water, healthy habitats for wildlife, and vibrant sustainable communities with abundant recreational opportunities. But we’ve been told for decades that in order to have those things our precious natural resources need to be managed by federal bureaucrats thousands of miles away.

As the legal wrangling over the Transfer of Public Lands movement plays out, the critical moral case for state control of public lands within state boundaries is being made by a growing list of federal debacles, injustices, waste and abuse.