Finally Home, but to What? After Obama Grants Him Clemency, a Federal Prisoner Rebuilds Life

Josh Siegel /

NEWBERRY, S.C.—He was never supposed to come back, but Douglas Lindsay is home now, 19 years later, where some things never change.

“You’ll be in church on Sunday?” is the first thing Lindsay’s aunt, Sally Cannon, asks as she bear-hugs him, because that’s how it always was, and how she thinks it will be.

Cannon is one of Lindsay’s extended family and friends who still live in the pocket of dimly lit trailers behind the train tracks in the Helena neighborhood of Newberry, S.C.

This is what used to be home, before prison, and it’s the first place Lindsay goes on his first day of freedom.

And yes, to answer Cannon’s question, on his first Sunday, Lindsay will sit in the pews of the familiar family church, Mount Zionist Baptist.

But Lindsay, if he has his way, won’t stay for long.

That’s because, from all the wisdom and regret accumulated from nearly two decades in prison, Lindsay, 47, knows that to make good on his second chance at life, he must make it his own.

“The thing about prison is if you let it, it will make you just watch life go by,” says Lindsay, whose deep, soulful voice and thoughtful manner made him the perfect messenger to lead Bible study for fellow prisoners. “It’s on you what you do while you are watching. So I got to see mistakes people made, mistakes I didn’t want to make again once I got out, and I laid the preparation so that I will be successful in my life.”

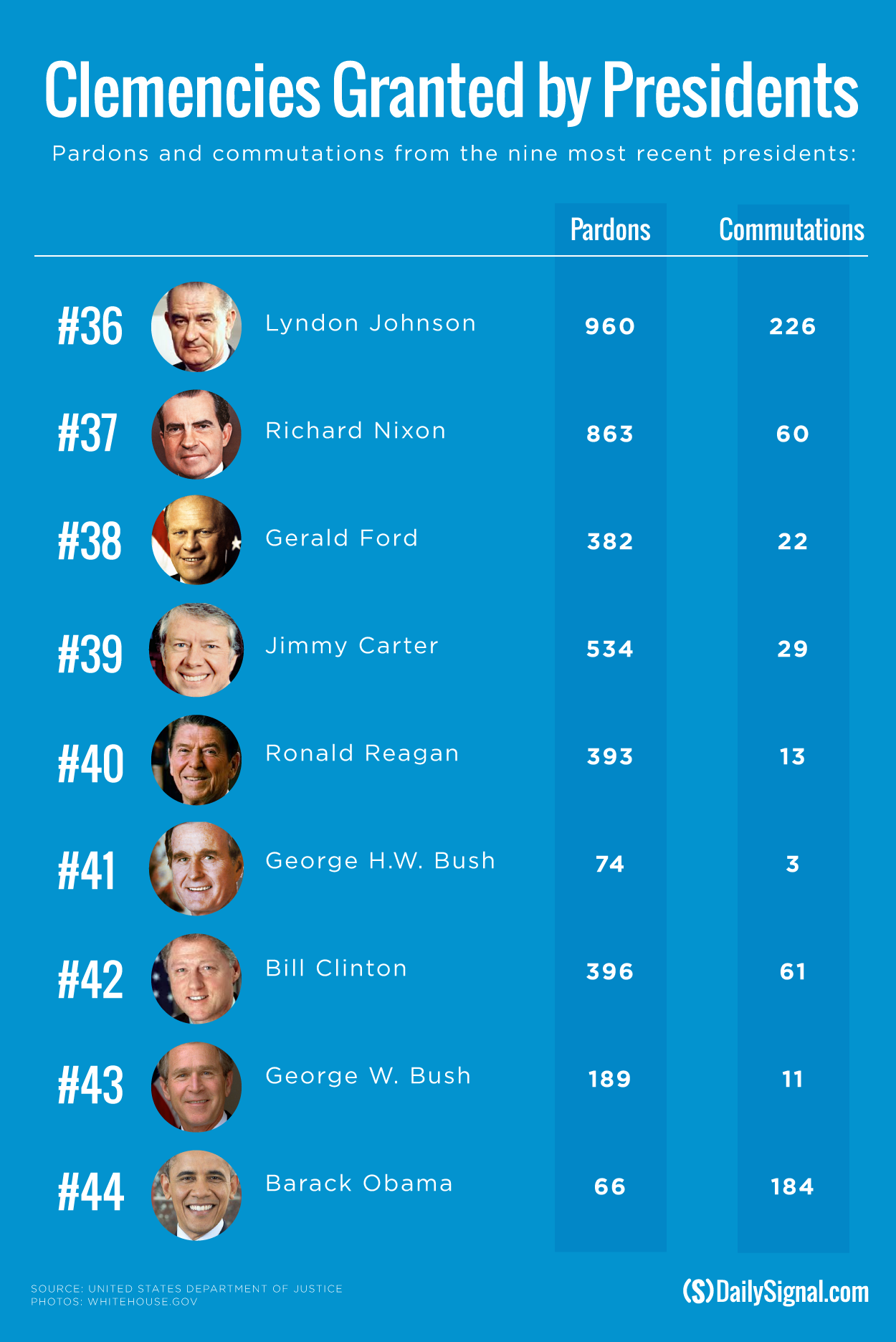

Lindsay was one of 46 federal inmates granted clemency by President Barack Obama in July.

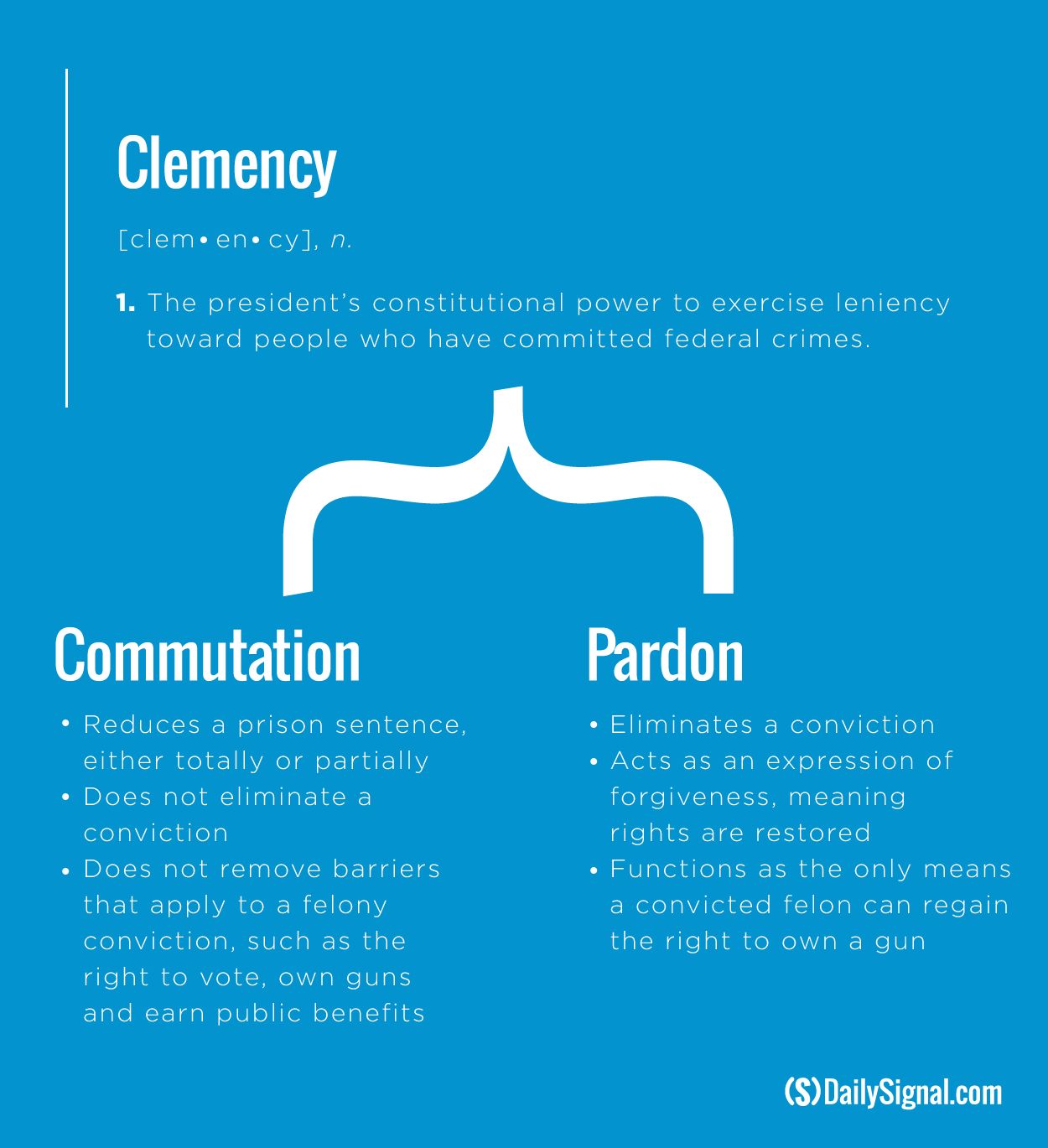

In receiving a commutation, a form of clemency that keeps the conviction but ends the sentence, Lindsay was spared what was supposed to be a life in prison for a nonviolent, first-time drug offense.

Now that he’s free, Lindsay does not want to just bear witness.

Instead, if he follows the path he planned for so long, Lindsay will incorporate his own ministry far from Newberry, maybe in Charlotte, N.C.

“I planned my dreams so many months and years out,” Lindsay says on this first official day of freedom, Nov. 10, when a cloudy morning makes way for uncovered sun. “I want to get to the point where I can have my day to me, and not have to be on someone else’s job working hard—letting my money make money so I can do what I want to do, which is my ministry.”

No Excuses

It’s not that Lindsay isn’t appreciative of Newberry, and the stable, zero-tolerance upbringing provided by his divorced parents—his mother, Betty, and late father, also named Douglas.

It’s just hard to reconcile with the past when it’s the place you did wrong, after living a childhood and early adulthood that had started so right.

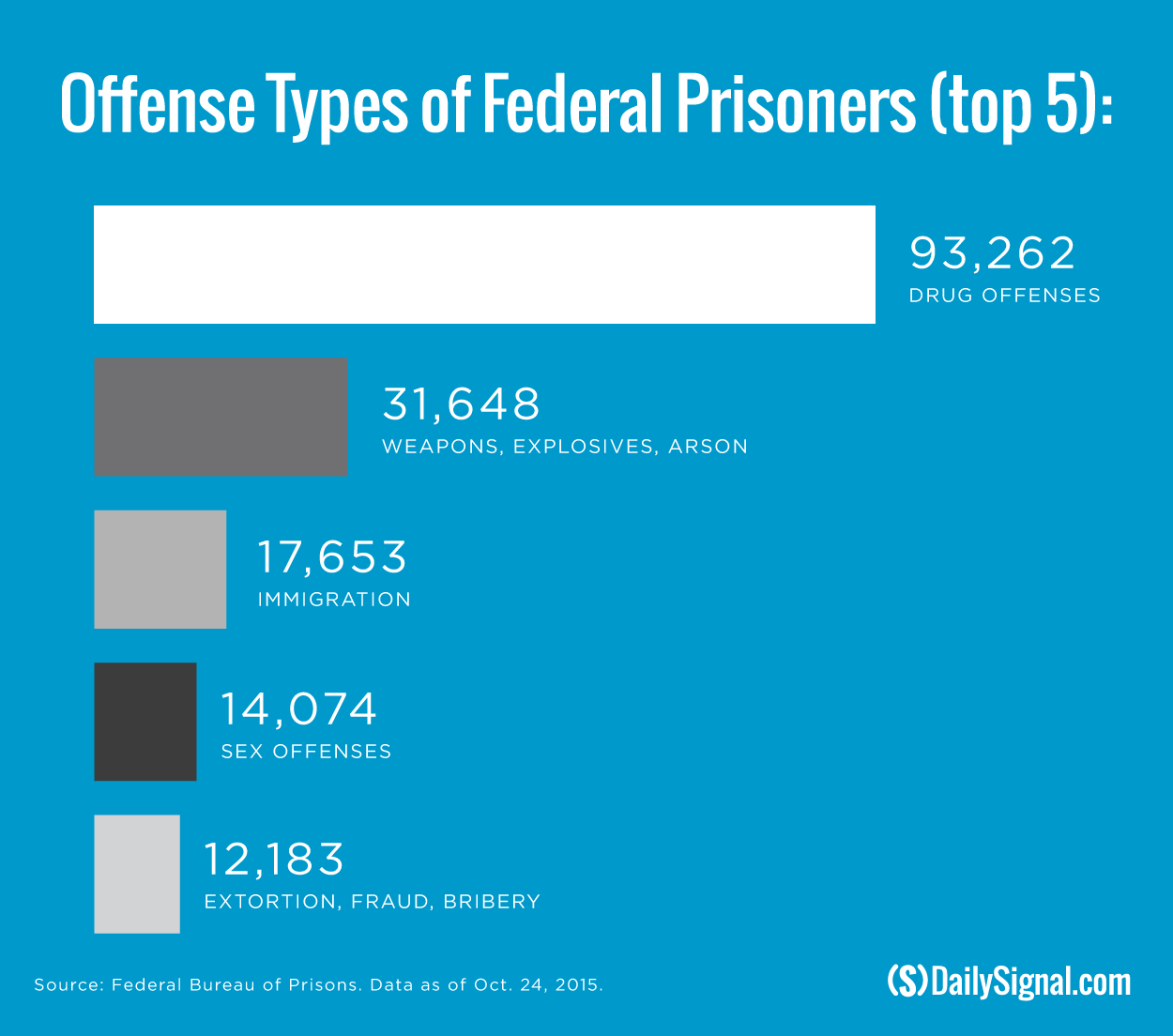

Before Lindsay sold drugs—first marijuana, then crack cocaine—he served his first four years out of high school in the Army. According to a report this month by the U.S. Department of Justice, 181,500 veterans (8 percent of all inmates) were incarcerated in state and federal prison in 2011-12.

Lindsay is also a college graduate with a bachelor’s degree in social work and was once employed in a job helping the mentally handicapped.

But selling drugs made financing his education easier, and everyone around him was doing it, Lindsay says.

“I never enjoyed selling drugs,” Lindsay says. “I saw it as a means to an end to hopefully get to the next level. I don’t make excuses. It was wrong. But that’s what I did.”

When he was arrested in May 1996 as part of a 14-person indictment, federal prosecutors alleged that Lindsay had done more than sell drugs.

According to his pre-sentencing report, obtained by The Daily Signal, prosecutors said Lindsay operated a crack house in Newberry that belonged to his aunt.

The report also says Lindsay denied his involvement in a drug conspiracy.

“I didn’t help the government because I didn’t want to be a snitch and to incriminate myself even more,” Lindsay says.

Lindsay now acknowledges that he used the house of his aunt, who was a drug user, as a place to keep and sell drugs, but he says calling it a crack house is too extreme. Prosecutors alleged Lindsay and other members of the group sold at least 1 kilogram of crack. He was convicted at trial.

Despite these factors, criminal justice experts say the biggest reason Lindsay was sentenced to life in prison as a first-time offender is that he decided to go to trial.

While all of the 13 other defendants pleaded guilty, cooperating with the government in exchange for reduced sentences, Lindsay, at the advice of a private lawyer hired by his mother, went to trial.

And he lost.

At the time, prosecutors often used the threat of long prison sentences mandated by federal sentencing guidelines to extract more guilty pleas, according to Molly Gill, government affairs counsel at Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

“People who plead guilty get rewarded with shorter sentences for testifying against co-defendants, and I think some of the problems we see are that it creates incredible incentives to sometimes inflate drug quantities, to inflate the bad behavior of co-defendants,” Gill tells The Daily Signal.

Gill continues: “So I think what we see here is the clear instance of the trial penalty in Douglas’ case.”

Lindsay would not have been sentenced so harshly today, Gill says.

Today, the sentencing guidelines are advisory, meaning a judge can use his or her discretion in administering punishment.

In addition, in 2010, Congress changed the law to reduce the sentencing disparity between offenses involving crack and powder cocaine.

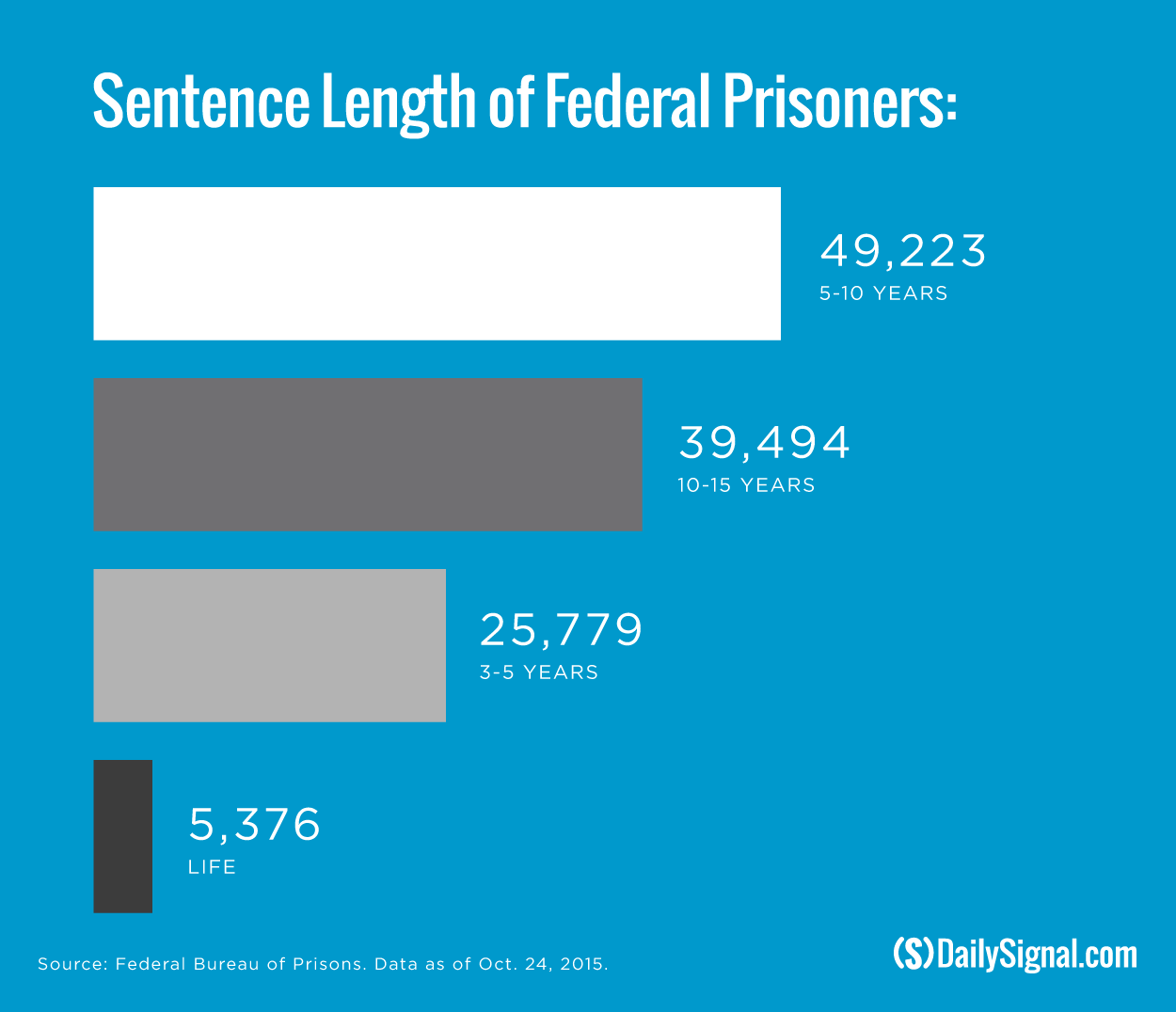

Yet all of this came too late for Lindsay. On Sept. 10, 1996, just before his girlfriend at the time pressed him to propose to her, Lindsay was sentenced to life in prison.

He was 28 years old.

‘Never Accepted the Life Sentence’

It might not seem like much, but for Lindsay, the gray speckles that invade the hair atop his head signify all he’s lost.

“I hate ‘Old School,’” Lindsay says of the nickname fellow inmates gave him. “I hate the gray hair with a passion. I tell people all the time. I know you see my gray hair on my head now, but I had a very young-looking face when I went to prison.”

He tries to hide the gray by dyeing it, but it’s hard to get back certain things.

His father died in 2003, and his mother, Betty, survived ovarian cancer. During her many visits to see Lindsay, his mother hid the severity of her tumor for fear of worrying her son. In a way, it was payback for Lindsay’s never telling his mother about his drug life.

“I lost a lot,” Lindsay says. He adds:

I went to prison at 28, so I lost all my 30s and 70 percent of my 40s. I always had the plan I would be married at 30, children after that, white house, picket fence like everyone else talks about. Whereas now, I don’t even know if I want children. Hopefully one day I will meet the right woman to get married, but I don’t know when. And then, with how long it takes, do I want to have a child at 50 years old? Life kind of passed me by.

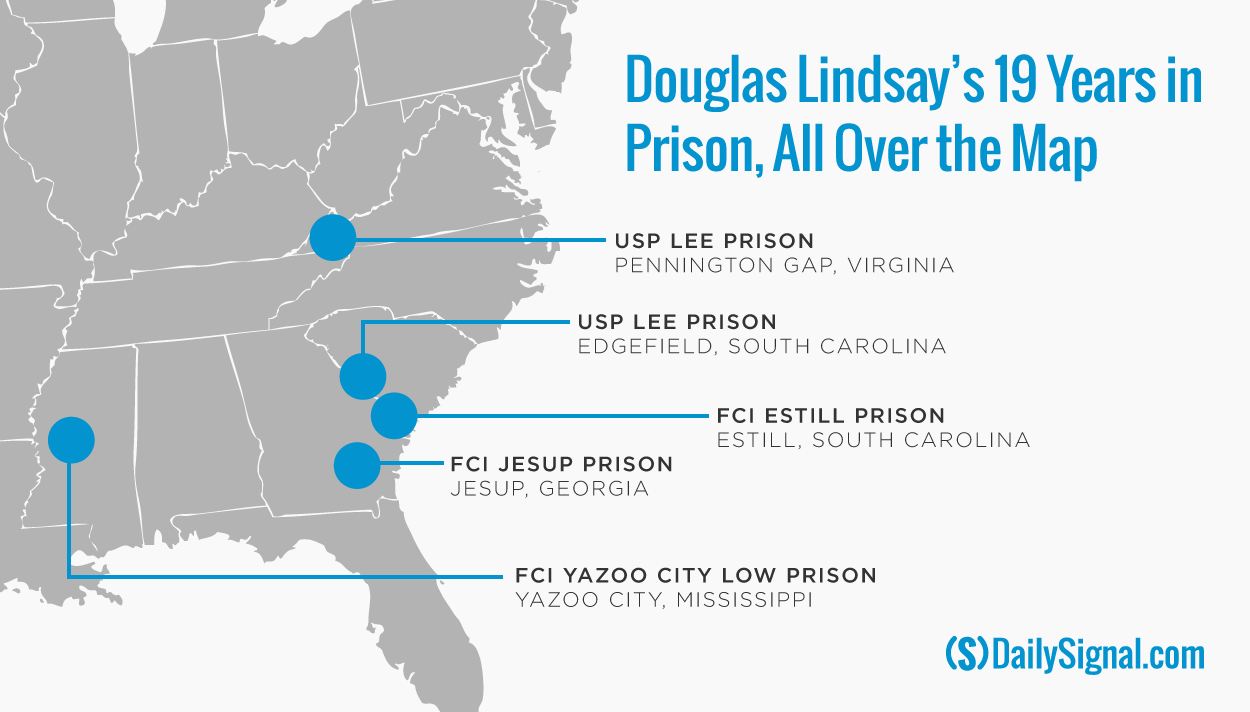

During Lindsay’s time incarcerated, which spanned five prisons across four states, he did his best to take hold of what he could control.

“I never accepted the life sentence or allowed myself to accept it,” Lindsay says. “I refused to believe I was going to spend my life in prison as a first-time offender. It didn’t make sense to me, and I refused to accept it.”

Lindsay spent most of his time in the law library, reading up on ways to appeal his case. When appeals failed, he found the option of clemency, and applied first in 2003.

He was rejected, under President George W. Bush, before Obama granted him freedom.

Lindsay says he read every single Harry Potter book more than once, because it’s hard to retain imagination in prison.

It’s almost clichéd to say, but, facing his lowest point, Lindsay found religion. Except he lived it, handwriting biblical lessons to mail to his mother, who would give them to people struggling on the outside.

“Most guys in prison tell you they found some form of religion,” Lindsay says, adding:

I am no different. Before, I went to church. But I didn’t give my life to Christ until I got in trouble, like most people. Being saved was the best thing that ever happened to me. I grew up cussing. In the Army, everyone cussed. As soon as I got saved, he took that from me.

It won’t mean much to employers, but Lindsay earned prison certificates in subjects such as investments, financial analysis, and real estate. He even traded stock through TD Ameritrade, purchasing shares over the phone using the $200 per month he made working a prison job sewing pockets on military jackets.

“I lost every time,” Lindsay says. “I was too fast.”

After being granted clemency in July, Lindsay spent his last month in a halfway house in Columbia, S.C.

There, still under the custody of the Bureau of Prisons, Lindsay got a taste of freedom, leaving the facility during the day to work on a construction site. He reported back at night to sleep, on the bottom level of a bunk bed in a small room that could hold five other inmates.

Many federal inmates on the way out of prison spend their last month or so in halfway houses, to ease the transition.

In early October, on the way from a minimum security prison in Jesup, Ga., to the Columbia halfway house, Lindsay, with his younger brother, Alcindor, enjoyed his first meal at Wendy’s, scarfing down a Baconator combo.

Alcindor, whom Lindsay calls “Al,” shopped with his brother for new clothes, buying him a couple of oversized polos. Though Lindsay felt old, he wanted to look fresh.

On Nov. 10 at 7:59 a.m, Lindsay checked out of the halfway house.

As he walked away with Alcindor, his back facing the past, Lindsay said softly, “I’m home. I’m home.”

Past to Future

For prisoners who’ve served lengthy sentences, the past is never too far behind; it’s all they know.

So when Lindsay says he wants to remake his own life, it’s more idealistic than reality at first.

On his first day on the outside, Lindsay had to report to a U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services office in Columbia, where he took a drug test and was told he can’t travel outside South Carolina unless granted permission.

Lindsay can be tested for drugs at any time, any place during the five years of his probation. If he violates these terms, he can be sent back to prison.

So Charlotte—his preferred destination to start anew—won’t be possible anytime soon. For now, Lindsay is living with his brother, Al, 43, in a middle-class Columbia neighborhood, some 45 miles from Newberry.

Al is also an ex-felon who sold drugs—marijuana, and then crack cocaine, like his brother. Al served seven years and nine months in state prison before being paroled in 2003. He has since recovered to rebuild his life, marrying, landing a good-paying job, and becoming a part-time minister.

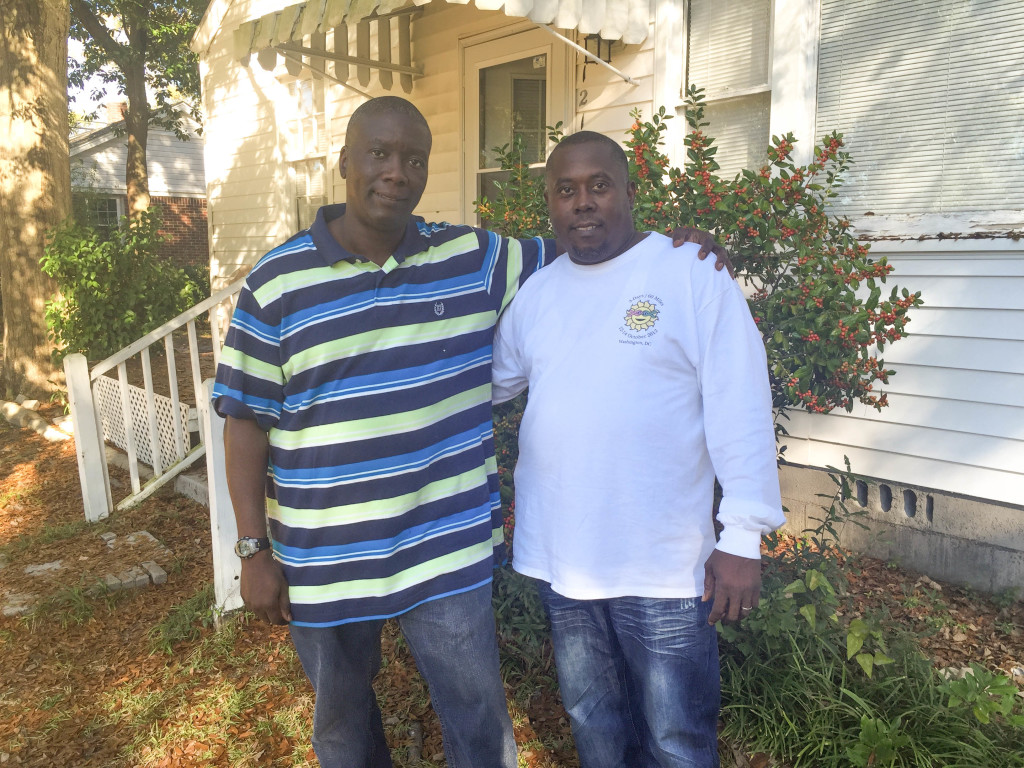

Lindsay is thankful to his brother, Alcindor, for providing a place to stay and helping Lindsay’s search for a job. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Though the brothers spent some of their childhoods in separate homes (Lindsay at his father’s, Al at their mother’s), the two are tight. Al, who is shorter, stockier, and more gregarious than his brother, faults himself for introducing Lindsay to drugs. Lindsay, whose calm, meditative demeanor (“level-headed,” as Al describes it) overrides any bitterness he may have, refuses to blame anyone.

He says he slept well on the first night at his brother’s place:

I slept like a baby. There are no guys hollering and screaming at 2 a.m., listening to music. I don’t have to worry about a count at 4 o’clock or some CO [correctional officer] going through my clothes. It’s hard to put it into words to be able to go and come as you please without anyone having to tell you what to do, when to do it, and how do it. So it’s wonderful.

This week, Lindsay says he will interview for the same position at the same job Al works, as an overnight forklift driver for a pasta plant, a place known to give ex-offenders a second chance.

On Sundays, Lindsay will attend their childhood church, Mount Zionist Baptist, and watch Al preach.

Lindsay will not preach there. He’s looking for his own church, his own way, but he’s constrained by the conditions of parole and dependent on his brother to live.

Yet Lindsay knows that the stability Al offers gives him an advantage over most ex-offenders, and he’s eager to embrace change in the small ways that he can.

“I am blessed enough that unlike a lot of guys who get out of prison and have to wonder where they’re going to work and most end up in fast food restaurants, I got real jobs lined up, and there’s no doubt I’ll get them,” Lindsay says.

On the same day he met with his probation officer for the first time, Lindsay passed his test for a driver’s permit, and he hopes to buy a car. Lindsay succeeded only after taking practice tests on his phone and failing miserably.

“I used the free computer on my phone, went on the free website, studied practically all night,” Lindsay says, mystified how a person today can use a phone—or a computer, as he calls it—for such a purpose. “Technology again came through for me.”

Gray hair and all, Lindsay even talks of getting on a dating site, where he can always PhotoShop his picture.

Marriage may come, after all, but that’s a dream, and dreams will have to wait.

“The stuff I learned, I want to use it out here, and then eventually in a couple years, maybe by the time I turn 50, I’m going to be into counseling or maybe even public speaking,” Lindsay says. “And of course, I want to incorporate my ministry. But the first thing I am going to be doing for my family—and really for me—is I am not going back to prison.”