Why 6 Government-Funded Insurance Companies Created Under Obamacare Collapsed

Melissa Quinn /

A government watchdog overseeing the Department of Health and Human Services delivered the grim financial state of nearly all of the co-ops—that collectively received $2.4 billion—created under Obamacare several months ago.

Now, following the collapse of six of the 23 that launched in 2013, the co-ops, or consumer oriented and operated plans, face an uphill battle to solidify themselves as competitors in the health insurance market.

To assist the co-ops in getting off the ground, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services disbursed $2.4 billion in start-up and solvency loans to the 23 co-ops created under Obamacare.

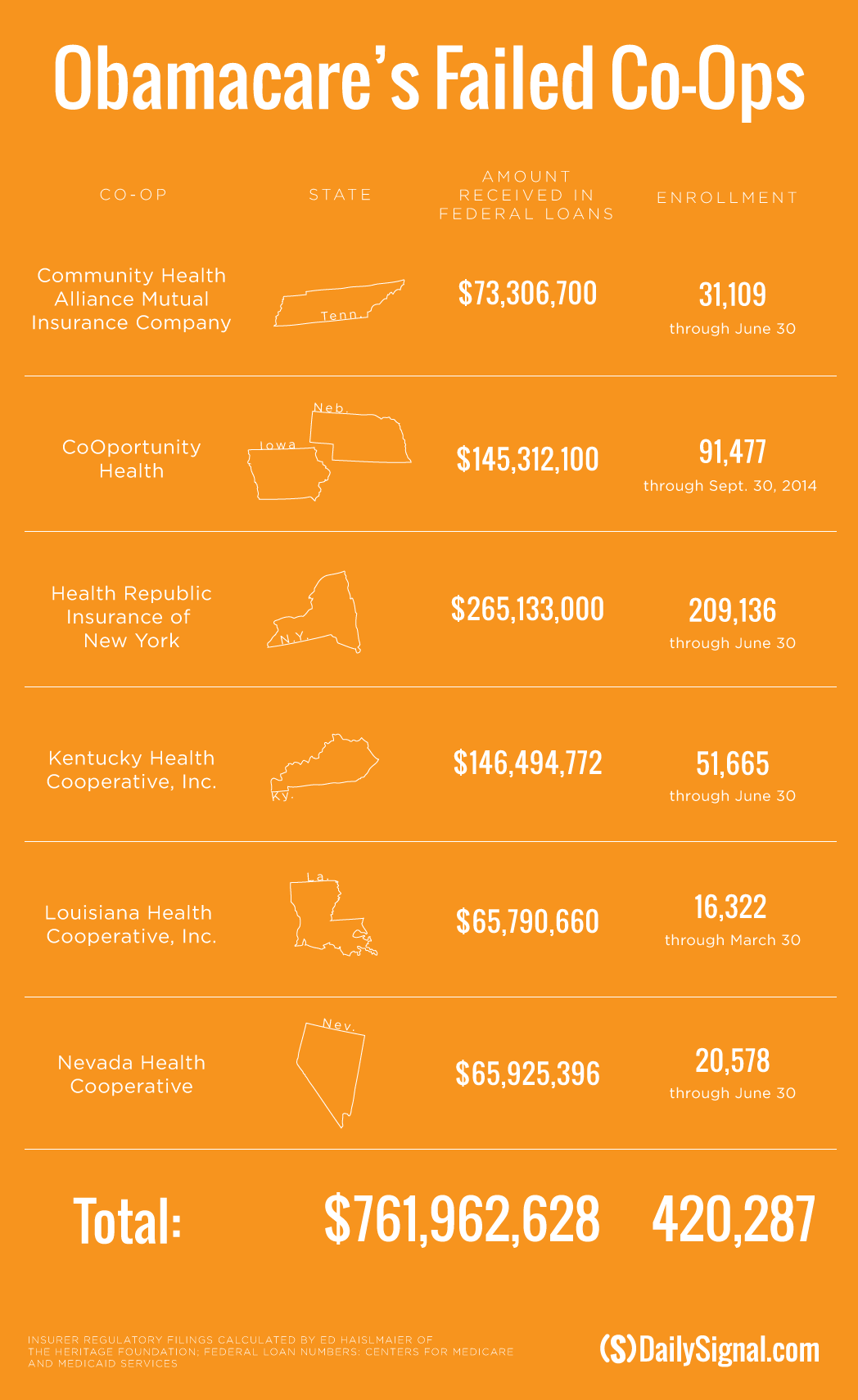

However, over the last 10 months, six co-ops, which collectively received nearly $762 million from the federal government, announced they’re closing their doors and pulling out of the insurance market for 2016.

As a result, more than 420,000 Americans who enrolled in health insurance coverage through the nonprofit insurers will lose their insurance and have been instructed to select new plans next year.

Additionally, an analysis conducted by The Daily Signal in February, along with a July report from the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General, found that 22 of the 23 co-ops lost money in 2014.

Thirteen of the 23, meanwhile, enrolled far fewer consumers than projected.

Industry experts predicted that some of the co-ops would struggle to survive, as the nonprofit insurers lacked the financial flexibility and deep pockets of their larger, more established competitors.

The collapse of the two biggest co-ops, Kentucky and New York, as well as the most recent closure‚ Tennessee, has brought into the question the viability of the remaining 17.

“If you can make it through for long enough, and if this market continues to grow, you can see a world where some [co-ops] become viable and profitable in future years,” Chris Sloan, a manager at Avalere Health, told The Daily Signal. “But they have to make it through now, the lack of risk corridors payment, a slower enrollment than expected. These are brand new companies, and it’s a brand new market, so you have to make it through the initial early years.”

“There’s been a lot of factors that have happened that have really blown the winds back at [the co-ops] that no one really expected.”

In a statement to The Daily Signal, Aaron Albright, spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said the agency recognizes that not all of the co-ops will succeed. However, he said they have increased competition in the health insurance market.

“As co-ops across the country continuously review their financial and operational positions heading into the next open enrollment period, we will work closely with state departments of insurance and co-ops to provide the best possible outcome for the consumer,” Albright said. “If a co-op has solvency issues, and we cannot rule out that others may this year, we will work with the states so that consumers have affordable options on the marketplace.” [Editor’s note: This statement was added after publication.]

Creating the Co-Ops

Co-ops, or nonprofit insurance companies, were created during the Obamacare debate in 2009 as a compromise between Republicans and Democrats, who wanted the health care law to include a public option, or a federal health insurance plan.

The Obama administration originally requested $6 billion from Congress to fund start-up and solvency loans for the co-ops, but lawmakers cut the funding to $3.8 billion in 2011 after members on both sides of the aisle raised concerns about the requested amount.

Then, Congress further lowered the funding for the co-ops to roughly $2.4 billion, the majority of which has been allocated to the 23 co-ops.

In addition to receiving federal dollars to launch, six co-ops requested and received additional money through solvency loans, which assisted the nonprofit insurers in meeting state solvency and reserve requirements.

The co-ops were designed to inject competition into areas where few companies provided coverage, and in their first year participating in the market, some saw higher than expected enrollment as they offered the cheapest plans available to consumers.

For example, CoOportunity, a co-op that received $145 million in loans from the government, expected to enroll just 12,000 consumers in Iowa and Nebraska during its first year on the exchange. By the end of the first open enrollment period in 2013, the co-op ended up enrolling 120,000—far exceeding its projections.

The co-op offered the cheapest plans available to consumers in the two states, and as a result of the influx of consumers, officials learned they didn’t make enough from premium costs to cover their customers’ medical claims.

CoOportunity announced in January it would be liquidated, leaving more than 100,000 customers to find new plans.

At the time the co-op announced its liquidation, it was not yet known if CoOportunity would be able to repay the $145 million it received in start-up and solvency loans.

In the months since CoOportunity announced it would be closing its doors, three more—Louisiana Health Cooperative, Health Republic Insurance of New York, and Nevada Health Cooperative—revealed they would follow suit.

Louisiana Health Cooperative received $65.8 million in loans, Health Republic Insurance of New York got $265.1 million, and Nevada Health Cooperative earned $65.9 million in loans.

Louisiana Insurance Commissioner Jim Donelon said in July that Obamacare’s “onerous burdens” have made it difficult for start-ups in the insurance market, such as the Louisiana Health Cooperative, to succeed.

Similarly, Stacey Hatfield, a member of Nevada Health Co-Op’s board, said in August the co-op was “winding down” operations because of “challenging market conditions.”

“We talk about the co-ops as an overall program,” Hatfield said. “They are, in fact, 17 different health plans. They’re co-ops because they were seeded with the co-op loans from the ACA, but they are, in fact, plans run by different people and different orgs and things like that. And there’s pretty big diversity in terms of who is running the co-ops. Part of it comes down to if they were able to make decisions, and pricing decisions, that were viable for the market.”

Coming Up Short

In addition to adjusting to new market conditions, Obamacare’s co-ops may face additional financial uncertainty due to payments expected under the health care law’s risk corridor program.

Earlier this month, the Obama administration announced that insurance companies would receive a significant amount less than expected through the program.

The risk corridor program, which is in place until 2017, was implemented to provide stability in the market. Under the initiative, companies that profited above a specified threshold shared a portion of the profit with the federal government. Those that lost more than a specified threshold, meanwhile, received assistance from the Department of Health and Human Services.

However, insurance companies that lost money—and thus expected to receive assistance from the government—learned earlier this month that they would receive just 12.6 percent of their requested risk-corridor payments.

“A lot were counting on that money,” Sloan said.

In the wake of the announcement, two co-ops—Tennessee Community Health Alliance and Kentucky Health Cooperative—announced they would be winding down operations and no longer offering plans in 2016.

Kentucky Health Cooperative received $146.4 million in loans, and Tennessee Community Health Alliance received $73.3 million.

“In plainest language,” Kentucky Health Cooperative interim Chief Executive Officer Glenn Jennings said, “things have come up short of where they need to be.”

Jennings said that the change to its risk-corridor payment led to “an unavoidable outcome.”

Kentucky’s co-op requested $77 million from the Department of Health and Human Services but will receive just $9.7 million.

Similarly, Jerry Burgess, president of Community Health Alliance, pointed to the lower than expected risk corridor reimbursement in a release notifying consumers that the co-op would no longer offer plans.

“Last week’s announcement of a risk corridor reimbursement of just 12.6 percent cast doubt on the collectability of over $17 million of CHA’s risk corridor receivable and led to an unavoidable outcome,” Burgess said.

Tennessee’s Community Health Alliance froze enrollment in January. The co-op planned to offer insurance on the federal exchange in 2016, but the Obama administration’s guidance about the risk corridor program “raised concerns” about Community Health Alliance’s future.

Sloan, the manager for Avalere Health, told The Daily Signal the reduced payments “dealt a pretty big blow” to the co-ops.

“I don’t think anyone expected that every single one of them was going to be successful. Obviously, the risk corridor payment was going to be the biggest thing you could change that could’ve led to improved viability for them,” he said. “If these organizations got their full risk corridor payments, that would’ve made a lot of their balance sheets look a lot better for this year.”

Sloan warned that the co-ops could be in for a similar surprise next year, as the program must be revenue-neutral, and payments could differ from their expectations next year, too.

In discussing the challenges the co-ops face, Sloan also pointed to the Department of Health and Human Services’ enrollment projections for 2016, which were announced today.

The agency said it expects to enroll 10 million Americans in health insurance through Obamacare next year—far less than the 21 million projected by the Congressional Budget Office in March.

“Co-ops, for the most part, they’re all only in exchanges,” Sloan said. “They’re designed for that market. That was the idea of the co-ops. … When you’ve got a market of that size—and 10 million isn’t that big for an insurance market—there’s inherently more risk, inherently more volatility in a small market.”

“It’s the only market they’re in, and it’s not a market that’s expected to grow significantly next year,” he continued. “Those are the two main things: one, the risk corridors may face a similar situation next year, and two, it doesn’t look like there are going to be significant enrollment changes next year. Put those two things together, and those are some forces working against the co-ops.”