Why 3 Men With All the Power Will Soon Parole More Prisoners in Alabama

Josh Siegel /

MONTGOMERY, Ala.—The three men holding all the power ask the prisoner’s biggest supporters why he deserves to rejoin the free world.

“Tell us why this young man is prepared to make changes,” implores Parole Board Chairman Cliff Walker, his spectacles lower than his eyes as he peers down at the file for Alabama prisoner No. 163856, Johnny Washington.

“We know you love him. We want to hear how he’s changed his ways.”

The pastor, a frequent preacher in prisons across the state, speaks first.

Washington, who has served 12 years of a 20-year sentence for second-degree assault, has found peace in religion, the pastor says.

Washington is the worship leader in the prison ministry. Before that, he completed drug treatment programs to kick the habit that has helped make him a repeat offender.

Next up is Washington’s forgiving wife, Carla.

She believes so much in her husband that she literally married him in prison, at a chapel there.

“He didn’t take marriage lightly,” Carla says softly, but not ashamedly. “I wanted to make sure he’d changed his ways. He has. That’s why I married him.”

Carla adds that Washington, if granted parole, would leave prison for a stable place. Her job at Mercedes-Benz can pay the bills to start, and near her Birmingham home, there’s a church where Washington can volunteer.

As with most hearings inside an oversized room at the Montgomery headquarters of the state Board of Pardons and Paroles, there is no one here to oppose the parole. The prisoner is nowhere to be seen, either.

In Alabama, prisoners cannot be present to hear their fate, though the general public can attend. Besides his supporters and a reporter for The Daily Signal, there is no audience at Washington’s hearing.

After about 90 seconds of testimony, it’s time to deliberate. The choice to free someone happens fast, and the board will preside over 80 or so cases today and upward of 7,000 this year.

Walker and the two other board members huddle over the file detailing the prisoner’s background.

They will decide Washington’s fate right here, right now, without ever speaking to him or conferring with each other before this hearing.

The verdict: parole granted. The decision is unanimous, as usual.

“Hallelujah,” the pastor exclaims. Carla bows her head, thankful that she has the chance to get to know the man she married.

Unusual Case

Johnny Washington is one of the lucky ones.

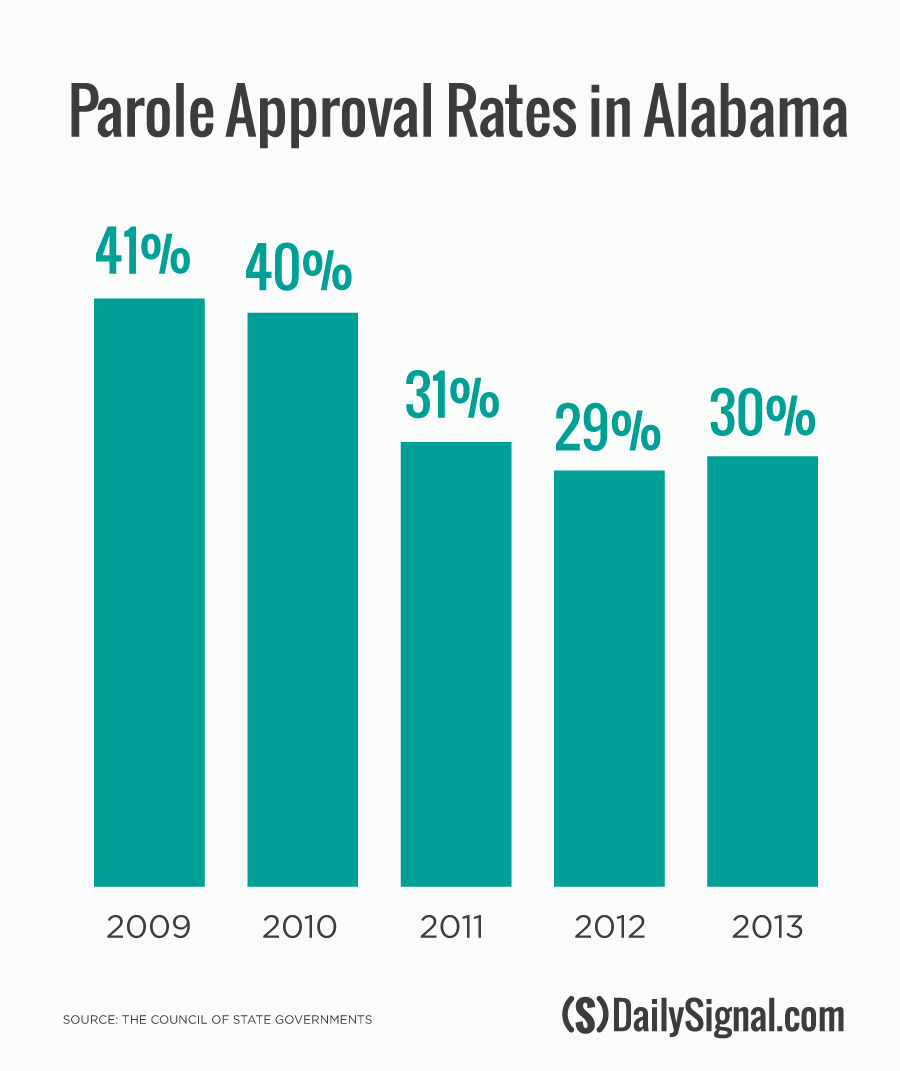

In Alabama, the parole approval rate dropped from 43 percent in 2008 to 30 percent in 2013.

The seasoned, governor-appointed members of the parole board have a simple explanation for this.

They say recent reforms to the front end of the criminal justice system—meant to keep more nonviolent offenders out of prison—have left them fewer parole-worthy candidates.

So the board is forced to consider prisoners such as Kirk Chandler, convicted of sodomizing a young girl—she attended his recent parole hearing all grown up, but still shattered—and Tommy Boldin, convicted of murdering a man and nearly killing the responding police officer.

The board denied parole for both men on the same Wednesday in late June that they granted freedom to Washington.

“You cannot outrun what happened in the past,” veteran board member Robert Longshore tells The Daily Signal.

“That got you to where you are. Some things you can’t outrun ever.”

Larry Armstead, a retired Montgomery police officer, attended the parole hearing of a man convicted of attempting to kill him while he was on duty. ‘It’s a life-changing event when someone tries to kill you,’ Armstead says. ‘You don’t forget it.’ (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Violent inmates like these would not benefit much from Alabama’s plan to ease its overcrowded prisons.

Rather, the bipartisan criminal justice reform legislation—passed by state lawmakers in May but still awaiting funding—would make changes designed to push the board to free more borderline prisoners. These men and women normally would be good candidates for early release in a resource-rich probation and parole system.

Alabama is far from normal.

Outside experts who have studied Alabama’s parole history believe that the drop in paroles is owed to problems at the back end of the criminal justice system.

These observers say the parole board’s decisions are influenced by the fact that if they vote to let a prisoner go, there aren’t enough parole officers to properly supervise the inmate’s re-entry into society.

Overwhelmed probation and parole officers currently have caseloads of 200 inmates each (70 would be ideal, officers tell The Daily Signal).

The budget of the Board of Pardons and Paroles has shrunk about 30 percent since 2009.

With less attention applied to helping offenders stay sober and find drugs and housing, the odds are good they will commit another crime.

“The function of parole academically and traditionally has been the protection of society through the rehabilitation of the offender,” says Longshore, who has deliberated over Alabama parole cases for a decade. “But austerity budgeting for parole has changed the philosophy from one of supervision to [one of] surveillance.”

‘Not Functional at All’

Elizabeth Planer and fellow probation and parole officers, squished into their trailer-sized Montgomery field office, say they want to do more.

“We should be here to help provide assistance and empower,” Planer explains.

Planer is the senior parole officer here, and her staff of 12 supervises more than 2,500 offenders. She says:

If I am supervising 200 people, I don’t have time to help provide assistance and empower. I have time to write reports—when they mess up. It’s not proactive, it’s very reactive. I am not saying we can cure everybody. But under the situation we are in now, we are not functional at all.

Officers such as Planer, who wear plainclothes but carry a badge and gun, have powers beyond the authority to arrest.

Their duties also require them to do pre-sentence investigations for every felony case that comes through Montgomery County circuit court.

Considered neutral parties, parole and probation officers compile information such as an accused offender’s arrest history and personal background, and legal details surrounding the case. They then recommend how a judge should sentence the person.

Probation and parole officers Elizabeth Planer, Steven Todd Hudson and Beverly Gilder struggle to keep up with heavy caseloads at their small field office in Montgomery, Ala. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Steven Todd Hudson, in his seventh year as a Montgomery probation officer, says he conducts 15 to 20 pre-sentence investigations per month.

That number is high, Hudson shares proudly—although it’s not a matter of choice, because for the past two years, he has had to handle all of the cases that enter Circuit Court Judge William Shashy’s courtroom. Typically, if staffing levels were what is considered appropriate, two officers would be assigned to each of six courtrooms in the county.

But perks come with the exclusivity of short staffing. Hudson says Shashy signs off on 98 percent of “what I want.”

Like any parole and probation officer, Hudson wants the offenders he sees to succeed. Prison is failure.

If he has to revoke parole or probation and send someone to prison, which he says is rare, he takes it personally.

“If they do end up in prison, I tell them it’s because you put yourself there,” Hudson says.

“Shashy is a really great judge because he will give you every option before prison.”

Although Hudson and Shashy have made a successful team, they aren’t keeping enough people from entering—and returning to—prison.

In fiscal year 2013, 40 percent of Alabama’s admissions to prison were violators of parole or probation, many for “technical” reasons such as missing an appointment with an officer, according to data compiled by the Council of State Governments.

Officers in part attribute that number to themselves. Short-staffed, they can supervise only in name.

Beverly Gilder, another Montgomery-based probation and parole officer, says she is able to spend only five to 10 minutes with each of the roughly 50 offenders she sees per day.

Obtaining employment is a requirement of supervision. Right now, Gilder hands inmates a printout listing the companies and other employers that will hire convicted felons.

Montgomery’s chicken plants are known to hire ex-offenders. Automobile suppliers, trucking companies and restaurants also welcome those seeking second chances.

But Gilder and her fellow officers don’t have the time to open doors. As Planer says:

When you come out of prison you are coming out in debt, with nothing, and out into an environment that is just negative all the way around. You are setting them up for failure if you are not giving them a chance.

‘Job to Help’

Supervision has to be adequate for parole to pay off, officers say.

Parole is unique in that those who are freed before the end of their sentence automatically are subjected to supervision in the community.

The parole board sets release terms, such as determining how often the offender must meet with a parole officer, and whether the offender must get treatment for drug or alcohol issues.

In Alabama, unless an offender is sentenced to death or life without parole, he or she gets a parole date within 15 years. If the inmate loses his chance at parole the first time, the case is reviewed again every one to five years.

But those continually denied parole—presumably because they’ve been deemed too dangerous to release—eventually serve their full sentence and are released with no supervision or conditions.

Around half of the inmates under the Alabama parole board’s jurisdiction complete their sentences in prison before being released without supervision.

Nationally, in 2012, one in five state inmates was released from prison without supervision.

The heart of the Alabama’s reform effort tries to encourage the board to grant more parole.

The new law provides money to hire 100 more parole and probation officers. As of July 30, the state employed 237.

The law also forces the parole board to create guidelines, based on best practices and scientific research, that inform its decisions on whether to grant parole.

“The state hasn’t ever really done any meaningful analysis to find out what works with community supervision,” says Bennet Wright, director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission. “This really is the next wave of criminal justice reform.”

The guidelines, as described in the legislation, should “promote the use of prison space for the most violent and greatest risk offenders” but “not create a right or expectation by a prisoner to parole.”

Currently, Alabama’s parole board members don’t have to disclose the reasons they reject parole. That would change under the new reform. The idea is to heighten scrutiny of the board’s decisions.

In Alabama and 23 other states, parole board files—including disciplinary records and other documents related to an offender’s case—are sealed from the public, according to The Marshall Project.

Another reform encourages the use of guidelines for how much time and effort officers should spend with each probationer and parolee.

When deciding the amount of attention to give, officers will be required to apply a risk-needs assessment focused less on the severity of the crime and more on the offender’s likelihood of breaking the law again.

Before passage of the criminal justice legislation, Alabama’s probation and parole agency already had been training officers with a tool originating in Ohio that has been adopted in other southern states. This system takes into account an offender’s socioeconomic background, peer groups, family support and job prospects when determining his or her needs.

“The problem with the way we supervise you now—based on your offense—is that it takes into account absolutely nothing about you as a person,” Planer says, adding:

Believe it or not, most of my murderers are my best people. Most of them don’t have any issues because they took care of their issue when they killed their issue. If we follow the idea that people are capable of change, then you can’t only judge them based on the one crime.

Under the changes, those adjusting more slowly to the outside world will be punished less harshly for violating terms of parole.

Instead of returning to prison, offenders who commit technical violations of probation and parole will endure short jail stays followed by continued supervision.

If they stay out of trouble, the reward can be great: The new law allows for early termination of parole for offenders considered low-risk.

“I don’t want them in prison,” Hudson says. “My job is to help them. I’m here to make sure they are enjoying their freedom, spending time with their friends and family and doing the right thing.”

A Chance at Parole

The goal of parole is to reward those who are doing well.

Valerie Harris is living the incarcerated life better than most.

Harris, 39, spends the time before her March 1, 2016, parole hearing at an alternative prison that declares that its mission is to “break the cycle of recidivism.”

Free to dress in everywoman clothes, she serves her life sentence amid positive messaging and ample opportunity.

The halls of the privately run prison, called Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility, are lined with spanking clean white walls.

Framed quotations, affixed to the walls every which way, are unavoidable:

“RISK BEING OPTIMISTIC.”

“HAVING A BAD LIFE? CHANGE IT.”

“STICK WITH THE WINNERS.”

Lately, Harris is behaving as if she has gotten the message.

In the unusual world of this medium-security prison, inmates (or residents, as officials call them) are able to govern themselves in a “rotated chain-of-command” structure.

Harris started at the bottom, as a “service crew” member. She has risen to become “senior coordinator,” the top of the top.

Female residents learn carpentry skills in the wood shop at the Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility, a medium-security prison known for alternative treatment options. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

To get there, she successfully completed a class to combat substance abuse.

She’s taking a heat and ventilation class, with hopes of developing carpentry skills that will make her employable if she ever again sees the real world.

She’s writing a business plan, to provide the blueprint for the nonprofit she hopes to start so she can help troubled teens.

In casual conversations, Harris uses textbook words such as “recidivism.” She recalls unprompted how states, and the federal government, are reforming the criminal justice system to help people like her.

“I have to stay up on the law,” Harris says. “I’d be stupid not to, considering my case.”

Case Study

Harris’s case—despite her seemingly uplifting circumstances—is not all that it seems.

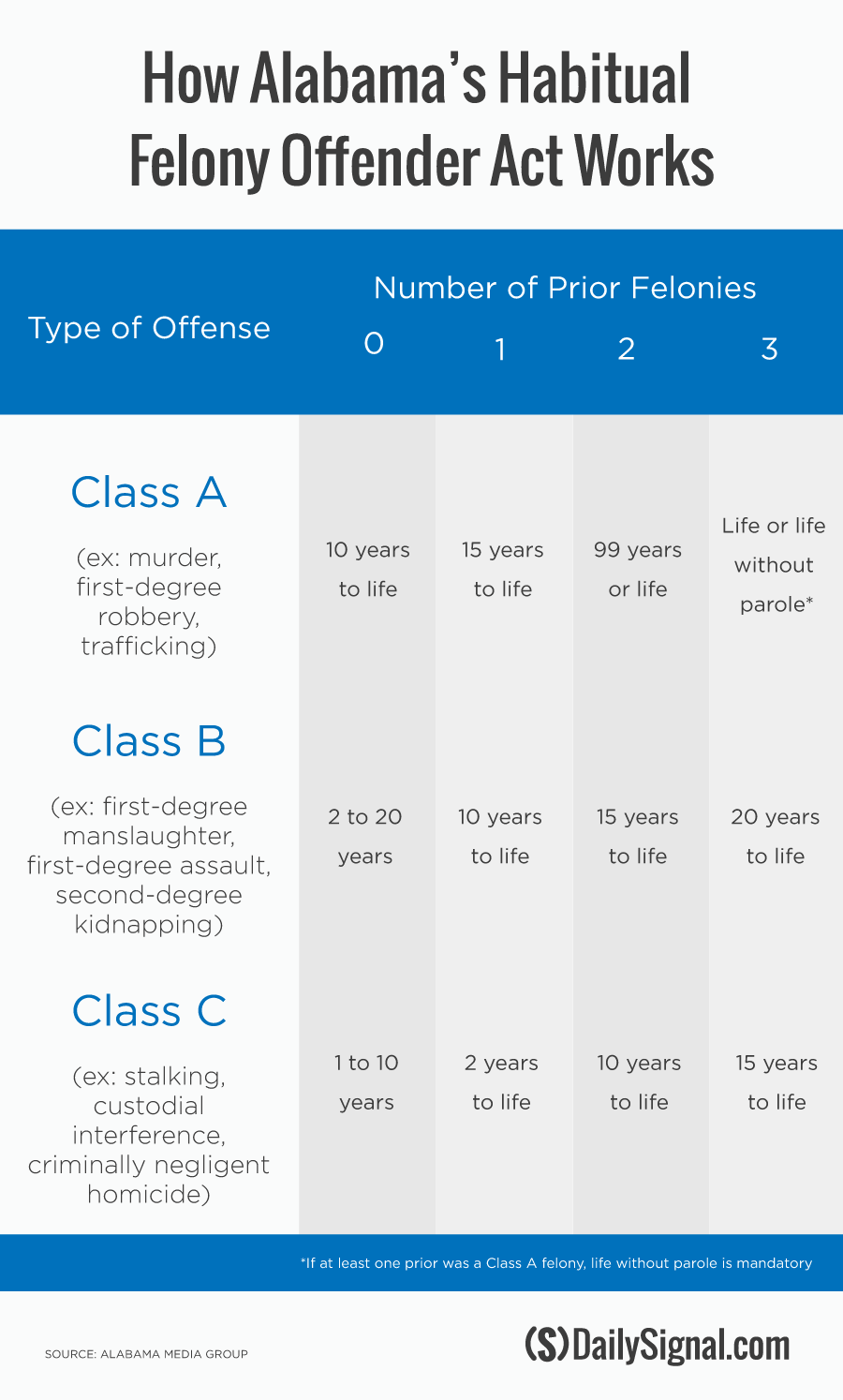

In 2006, she was sentenced to life in prison, with the opportunity for parole, under Alabama’s tough three-strikes law officially called the Habitual Felony Offender Act.

Experts in large part blame the law, passed when nationwide fear over repeat offenders was high, for Alabama’s severely overcrowded prisons.

If you are convicted of a felony, the statute imposes additional prison time for prior felony convictions.

The offense Harris received a life sentence for, a conviction for trafficking cocaine, was not enough by itself to put her away for that long.

In fact, because she was convicted of selling such a small amount of cocaine—more than 28 grams but less than 500—under Alabama law, she would have been sentenced to a minimum of three years in prison.

But this was not her first offense, so Harris wasn’t sentenced based on that crime alone. She already had been convicted for drug possession in both 1997 and 2002 and was sentenced to probation each time.

Because her 2006 trafficking offense is considered the most serious type of felony (Class A), the habitual offender statute required Harris to be punished more harshly because of the prior convictions—no matter how minor.

“I certainly believe I would have imposed a more appropriate sentence under the circumstances of her case if our law had given me that discretion,” says Teresa Pulliam, the Jefferson County Circuit Court judge who sentenced Harris on the drug trafficking conviction.

Harris has had chances to overcome her tough sentence.

According to Eddie Cook, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Parole’s assistant director, Harris won parole twice before (in 2009 and 2013).

But once outside the confines of prison, she picked up a new drug charge.

She most recently was sent back to prison in March 2014.

In September, good behavior helped Harris get transferred from a maximum-security prison known for toxic conditions to the relative comforts of Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility.

The 381 residents staying here have been hand-selected by the Department of Corrections.

Valerie Harris, incarcerated on a life sentence for trafficking cocaine, awaits her 2016 parole hearing. “I just can’t give up,” she says. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

As she awaits yet another parole opportunity, Harris says she better appreciates the costs of her actions—and all that she’s lost.

Harris lost her mom seven months ago. Harris was incarcerated during her mother’s last days.

She got a tattoo of her mother’s name, Annie, on her right forearm as a way to overcome the death.

“I’m not mad about where I am,” says Harris, whose dark hair is showing gray strands. “I feel like this was the hand I was dealt.”

‘Every Angle’ to Free

Experts say that under the new guidelines for the parole board, a case such as Harris’s would be scrutinized for what it is—not for what it was.

“Under the guidelines, they will look at the totality of a person’s case to determine if he or she is a good candidate for parole,” says Andy Barbee, a research manager with the Council of State Governments, an outside group that helped Alabama enact its reforms.

Barbee explains:

The length of a person’s sentence—and the sticker shock of that—will not drive the decision. It’s more about addressing things that relate to recidivism. ‘Is the person getting programming? Have they developed new skills? Do they have a reentry plan?’ They will be evaluated on a level assessment field.

Parole board members are more circumspect.

In interviews, the three men welcome the changes but reject the idea that the reform will alter how they do their job.

“It’s what we already do now put in writing,” says William Wynne Jr., who is in his eighth year on the board. “We will just memorialize our thought process.”

The board members say they already take a comprehensive view of a case—and look beyond the offense itself.

During a reporter’s attendance of a day of hearings, Walker, the normally cerebral chairman, pushes back at the grandmother of Alonzo Smith, who has just been denied parole.

Smith is incarcerated for attempted murder, but that’s not the problem, Walker tells his grandmother:

We are not letting him stay in prison. He’s letting himself stay. He’s been out of control even in prison. We look for every angle to let people out. The key is in his hands.

When the board does deny parole, as in Smith’s case, members insist they go out of their way to explain their reasoning—even though they don’t have to make that information public.

“Boards in the past—and I’m not being judgmental of prior parole boards—just sat here, listened to the testimony, made a ruling, and said go and get on out of here,” Longshore says.

“This board feels for this process to mean anything we have to put something out there,” he says. “We could not be clearer in how we do that now. But if they want to memorialize that process, we have no objection whatsoever.”

The three board members acknowledge that the extra resources on the outside will push them to free more inmates. Longshore says:

I can tell you why this whole thing will lead to more paroles. If we have more parole officers who can adequately supervise offenders, who can make sure they are in programs, marginal cases are more likely to be paroled. I can guarantee we will parole more people.

Waiting for ‘Lucky Day’

Back at Alabama Therapeutic Educational Facility, inmates can taste freedom but aren’t there yet.

Five-on-five hoops games and bouts of wall ball make the prison feel alive.

In a classroom decorated with the faces of presidents and birthday wishes written in magic marker, residents study for the GED, the next step in a life that hasn’t followed the normal steps.

Cognitive-behavioral training classes at Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility prepare inmates for life after prison. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

A spacious, female-only, dorm-style room with eight neatly made beds and a private bathroom feels close to home. But a cat-themed calendar on the wall counts down the days to the real thing.

Valerie Harris, after blowing her previous chances at freedom, may get another chance.

Harris says she regrets “being selfish” and taking her freedom “for granted.”

If she’s truly changed, another shot at parole will allow her to prove it.

“We believe in rehabilitation; we believe in redemption,” Longshore says. “If they go in there and do good things, they are a good parole prospect.”

And if she’s not there yet, Harris says, it means she hasn’t earned it.

“If I don’t make parole, it just means I have a little more room for growth,” Harris says. “I would see it as, ‘It’s just not my time.’ Hey, I may be lucky one day. I still have a chance. I just can’t give up.”