How Overcrowding Has Forced Alabama to Confront Its Prison Problem

Josh Siegel /

MONTGOMERY, Ala. – Inside a maximum-security prison hidden in a nowhere part of Alabama, nearly 1,300 inmates live for the past, most incarcerated for violent crimes they can’t ever leave behind.

A wall lining the entryway to St. Clair Correctional Facility is inscribed with a hopeful quotation: “Envy is a waste of time. You already have all you need.” But the wisdom doesn’t exactly ring true in a state with a prison system so overcrowded (at 195 percent capacity) that basic needs go unmet.

Two hours south, in the historically rich state capital of Montgomery, the three governor-appointed members of Alabama’s parole board use their unique power to decide whether to free more fortunate prisoners—those eligible for early release.

Their consideration is clouded by the fact that if they vote to let a prisoner go, there aren’t enough parole officers to properly supervise the inmate’s re-entry into society. So the odds are good he will commit another crime.

And in a Birmingham courtroom, a judge bound to abide by a tough 1970s sentencing law—eased somewhat by recent reforms—must send a repeat drug offender to a prison system where not enough convicts are coming out to compensate for those going in.

Alabama is reforming its criminal justice system because a complex web of interconnected problems left it near implosion—a mess of spent money, wasted lives and broken families.

As Alabama becomes the latest conservative state of the Deep South to reform its criminal justice system, the challenge, state leaders and outside experts say, may be the greatest yet.

‘Public Safety First and Foremost’

Alabama has the most overcrowded prison system in the nation. Worse than California, where the prison system also was nearing 200 percent capacity when a federal court order forced the state to immediately reduce the population to 137.5 percent capacity.

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the decision, ruling that conditions in California’s overcrowded prisons violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

“We don’t want the federal government ruling our prison system, and we are dangerously close to becoming another California,” says Alabama State Sen. Cam Ward, the Republican chairman of the Judiciary Committee who sponsored the reform legislation.

“We dare defend our rights—that’s our state motto,” Ward says. “I’ve toured every prison in the state, and I can tell you my biggest concern is this: I want public safety first and foremost. And second, at the end of the day, why release a bunch of inmates because we ran a sorry system, when we can improve the system at a small cost without letting a lot of nasty people out? That’s the direction I saw us going.”

Alabama State Sen. Cam Ward, the Republican chairman of the Judiciary Committee, says he sponsored the reform legislation because ‘you want to be smart about crime.’ (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

In late June, one month after Alabama followed Texas, Georgia and South Carolina in passing a bipartisan plan to relieve prison overcrowding, The Daily Signal spent a week on the ground to explore the state’s criminal justice system.

The visit came at an awkward time, when criminal justice officials act as if the plan will proceed even though they can’t begin to implement it yet.

Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, a Republican, signed the reform bill into law on May 21, but the plan still is not funded.

During the week of Aug. 3, the Republican-controlled state legislature is slated to interrupt summer recess to convene for a special session. Ward, who says lawmakers must come up with an additional $12 million to bolster the $394-million prison budget, insists he is “very confident” the plan will get funded.

The reform measure, which is supposed to go into effect in January and take five years to implement, is expected to cut Alabama’s prison population by more than 4,200 (a 30-percent reduction), avert more than $380 million in future costs, and provide supervision for every single inmate released from prison.

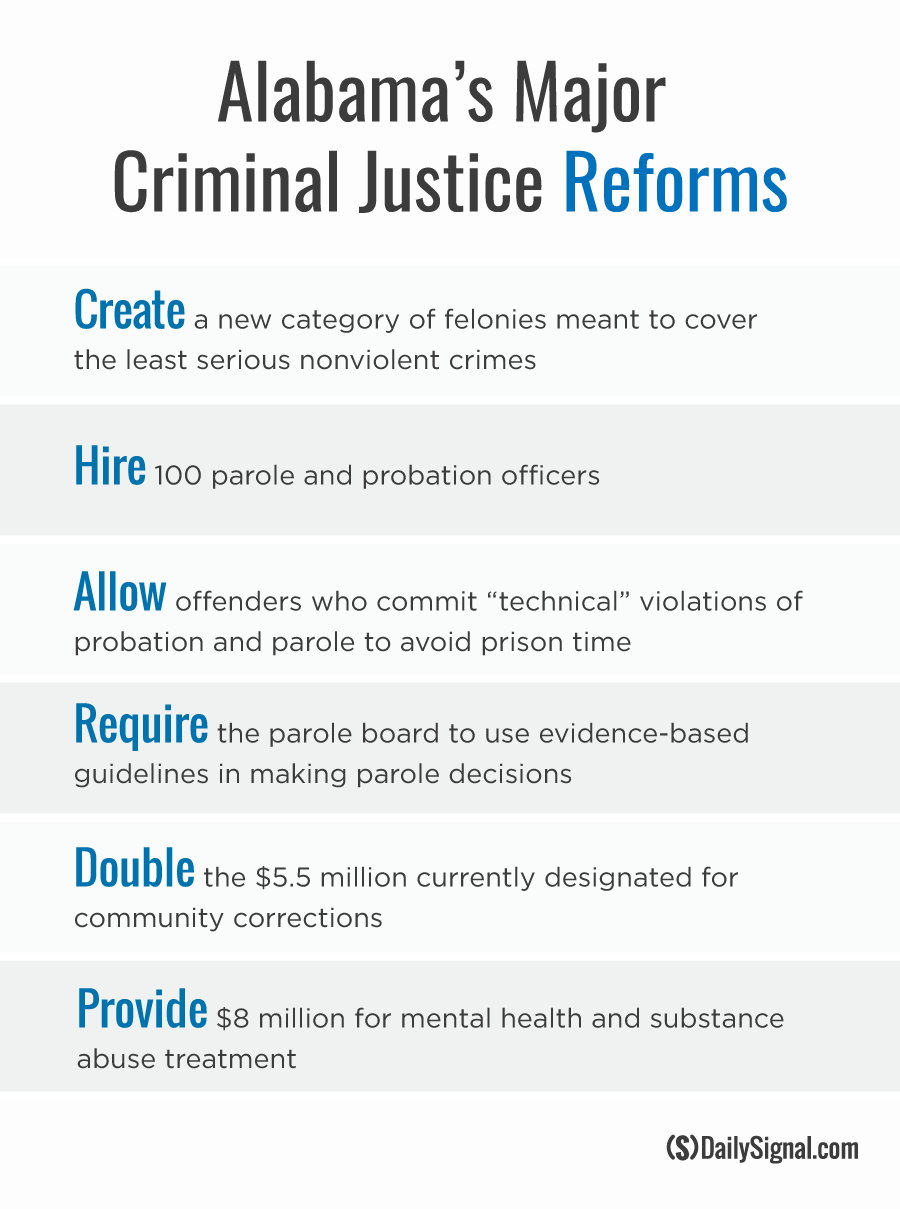

The changes, expected to cost between $23 million and $26 million per year, include:

- Creating a new category of felonies (Class D) meant to cover the least serious nonviolent crimes. Those sentenced under the new category rarely would go to prison.

- Hiring more parole and probation officers to supervise inmates on the outside.

- Establishing less severe punishment for those who commit “technical” violations of probation and parole, such as missing an appointment with an officer.

- Forcing the parole board to disclose the reasons they reject parole. Parole approval rates in Alabama dropped from 43 percent in 2008 to 30 percent in 2013.

- Giving convicted felons greater opportunities to serve their sentences in their home communities rather than prison. In a community corrections program, adopted and run at the county level, the offender must attend counseling and treatment programs at a facility during the day, with the freedom in most cases to return home at night.

The National Picture

State leaders say these reforms are just the beginning of what should be a long-term process.

The hope is that the changes in Alabama and other states will serve as models at the national level.

“Financial costs are not the only reason states are undertaking these efforts,” says John Malcolm, director of The Heritage Foundation’s Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies. Malcolm adds:

There is a human cost to the family members of offenders, particularly children, many of whom struggle financially and emotionally with a parent behind bars and who sometimes end up turning to crime themselves. Governors are saying, ‘We ought to see if there are things that can be done to address the problems prisoners released from prison face, such as substance abuse problems or a lack of education or jobs skills, so that they would be less likely to recidivate once they are released.’ The results so far look very promising.

With state-level reforms amping the pressure, the White House and Congress—seizing on bipartisan concern over the growing U.S. prison population—also are pushing to reduce federal sentences for nonviolent crimes.

Conservative Republicans, including Sen. Mike Lee of Utah and libertarian-leaning Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, have united with liberal Democrats such as Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey to take on the prison problem.

Roughly 750 of every 100,000 Americans are incarcerated, the highest rate of any Western nation. Lawmakers from both sides blame federal overreach for making it this way.

So Alabama has decided to act alone.

“What we want to do is make sure the most dangerous people in prison stay in prison, and that those who commit the most dangerous crimes go to prison,” Ward explains, adding:

But we don’t want a system where we are locking up people for nonviolent, what I call non-victim, crimes just to say we are tough on crime. Because in fact, you’re spending a lot of taxpayer money that can be spent in better ways, and much cheaper, to make sure people never commit a crime again. You want to be smart about crime. That’s the one issue in this country that I’ve seen bipartisanship on.

Challenges, but No Excuse

St. Clair Correctional Facility doesn’t appear overcrowded.

On this beachy June day, the prison in Springville, Ala., even seems orderly and peaceful.

Standing under the shade of a spacious courtyard, prisoners line up and wait their turn to purchase snacks.

These men are used to waiting—most are here for life for violent crimes, many for murder. Almost 450 of them will never leave because they have life sentences without the opportunity for parole.

Their matching white pants and shirts—“Alabama Dept. of Corrections” imprinted like a stamp on the back—signify the loss of ownership of their lives.

The brown paper bags they carry contain personal goodies—some have chips, others have candy, many possess deodorant—because it’s one thing they can control.

As the prison’s new warden walks past the line of inmates, he is not scared.

“I’ve worked in prisons 32 years,” Dewayne Estes says. “If they wanted to kill me, they would do it by now.”

Inmates line up to buy snacks from the canteen at St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, Ala. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

Estes was transferred from another prison to St. Clair earlier this year after the previous warden was accused by a prominent prisoners’ rights group of contributing to a culture of violence here.

In a lawsuit against the Alabama Department of Corrections, the Equal Justice Initiative claims St. Clair inmates were subjected to cruel and unusual punishment because of inadequate security and unsafe conditions.

In April, 15 inmates were treated for injuries after an assault on a corrections officer.

Before Equal Justice Initiative called for a new warden, four prisoners were killed during inmate-on-inmate incidents at St. Clair between 2013 and 2014.

And this past June, 10 inmates who were suspected of conspiring to assault corrections staff were transferred to different prisons.

Estes has come to restore order, and he seems to have the inmates’ respect.

The line of inmates greets him as he walks through: “How you doing, sir?”

“You doing all right?”

Estes is defensive about the overcrowding label.

“In the double-bunked traditional sense of overcrowding, St. Clair is not overcrowded,” he says.

As Estes ticks off statistics on the prison from his office desk, a photograph of his dog, Bella, looks back at him, softening the hardness of his demeanor.

As of July 16, St. Clair had 1,323 prison beds and 1,297 inmates. In September 2014, there were 26,029 inmates overall in Alabama’s prison system, which is designed to serve 13,318.

But at St. Clair, overcrowding is felt in other ways.

Estes says he has 184 corrections officers—including 34 added in June.

Before they came on, St. Clair had 38 percent less security staff than required by its design. Now, it is staffed 24 percent short of capacity.

That shortfall likely contributed to the unrest in April.

“We never lost control of the facility,” Estes says:

It was not a riot situation. But we house inmates who have a propensity towards violence and escape. And we have staffing challenges. Overcrowding hinges around your number of faculty. And when you are down that many officers, morale is not the highest thing right now. But that is not an excuse.

‘Incredibly Complex’

How did Alabama, which has the nation’s fourth-highest incarceration rate, get this way?

It depends on who’s talking.

In Alabama, the consensus on tackling criminal justice reform is overwhelming: The state House passed the bill by a 100-5 margin, and the Senate followed suit with a 27-0 vote.

But talk to criminal justice officials in Alabama, and you’ll get a different perspective on what caused overcrowding in the state’s prisons.

“Criminal justice reform in Alabama is incredibly complex,” says Bennet Wright, executive director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission, an agency created by the legislature in 2000 to study sentencing policies with an eye toward reducing the prison population.

“If you want to move the needle on criminal justice reform in Alabama, you have to touch a variety of policy areas, and at the same time you have to be cognizant that it touches all three branches of government,” Wright says, adding:

You can’t just change sentencing to change the whole system. At the actual sentencing phase, that’s a judicial function. However, you have an executive branch function in the parole board that can make the decision whether to actually let the inmate out. This reform bill is the first attempt to wrap its hand around the entire criminal justice problem.

Bennet Wright, executive director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission, blames prison overcrowding on complex sentencing laws. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Ward, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, convened a task force of leaders from across the criminal justice spectrum, including Wright, in hopes of creating a plan acceptable to everyone.

Members included district attorneys and victims’ rights advocates, who—dubious that keeping nonviolent offenders out of prison would reduce crime—pushed the legislation further to the right.

Judges and representatives of community corrections—having worked together to reduce recidivism through promoting alternatives to prison—pushed the bill to the left.

The state contracted with an outside group, the Council of State Governments, to issue recommendations to the task force.

The Council of State Governments has worked on criminal justice reform with states such as Texas, North Carolina, Kansas and Hawaii. The organization’s researchers spent about 18 weeks in Alabama studying the penal system through a nonpartisan, data-driven lens.

“It would be one thing if the problems in Alabama were only related to the fact that, like everyplace else, there is not enough resources,” says Andy Barbee, a research manager with the group. “Or if, like everyplace else, there were overworked caseworkers and a lack of capacity to treat people.”

“But the problems in Alabama go above and beyond resources,” he says. “There are a lot of other factors that make it one of the most complex states.”

To carry impact, the Alabama reform effort would have to address every aspect of the criminal justice system, from sentencing to supervision to community corrections.

“It’s not about changing this or that—it’s changing everything you do once somebody comes in the system,” Wright says:

A lot of people thought the bill could have gone further. But this is not viewed as, ‘We have done this, we can push this to the side and the issues have been resolved.’ This is the beginning of a massive criminal justice overhaul.

‘Catch-All for Everybody’

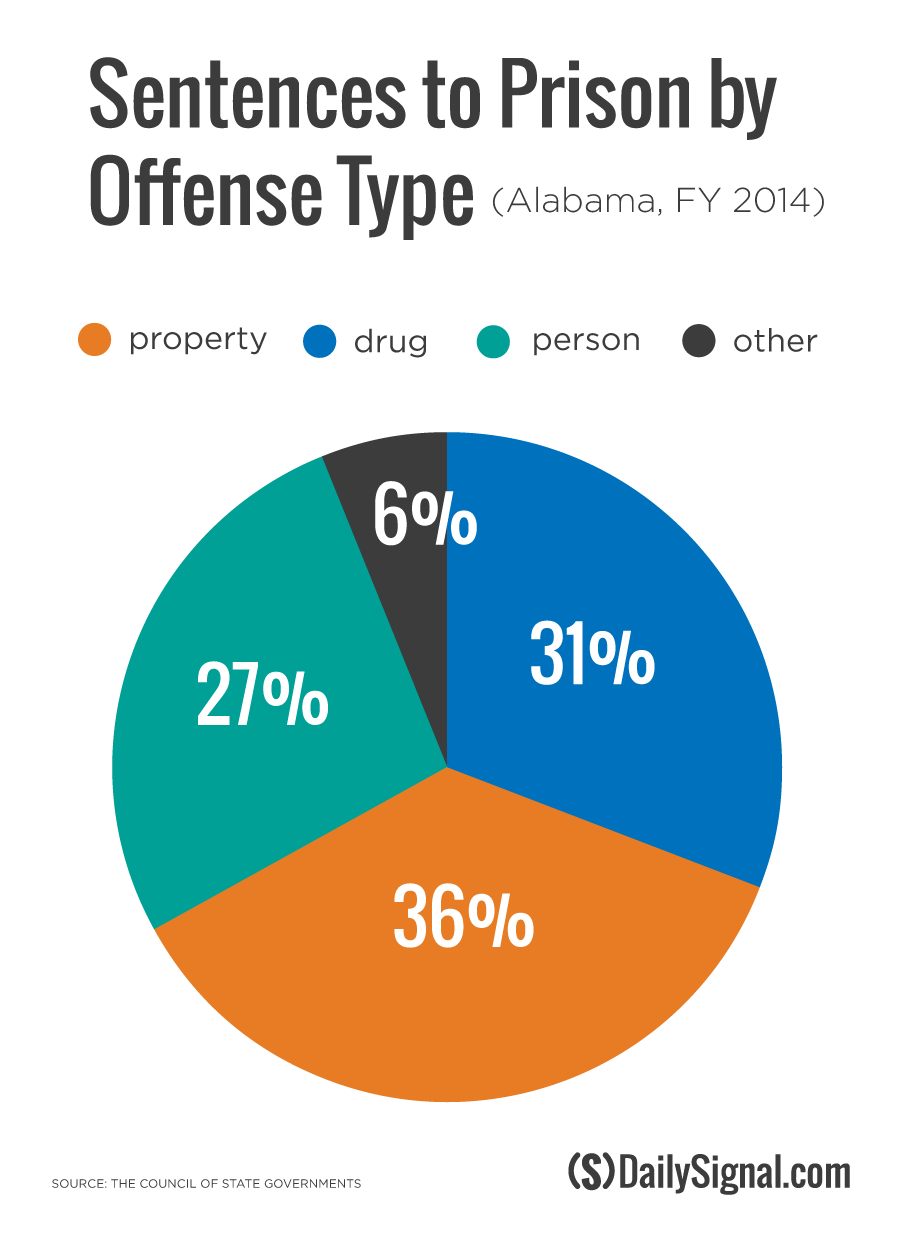

Here’s a weird stat: In fiscal 2014, only 27 percent of prison sentences in Alabama were for crimes with a victim.

In fact, two-thirds of prison admissions were men and women convicted of drug and property offenses.

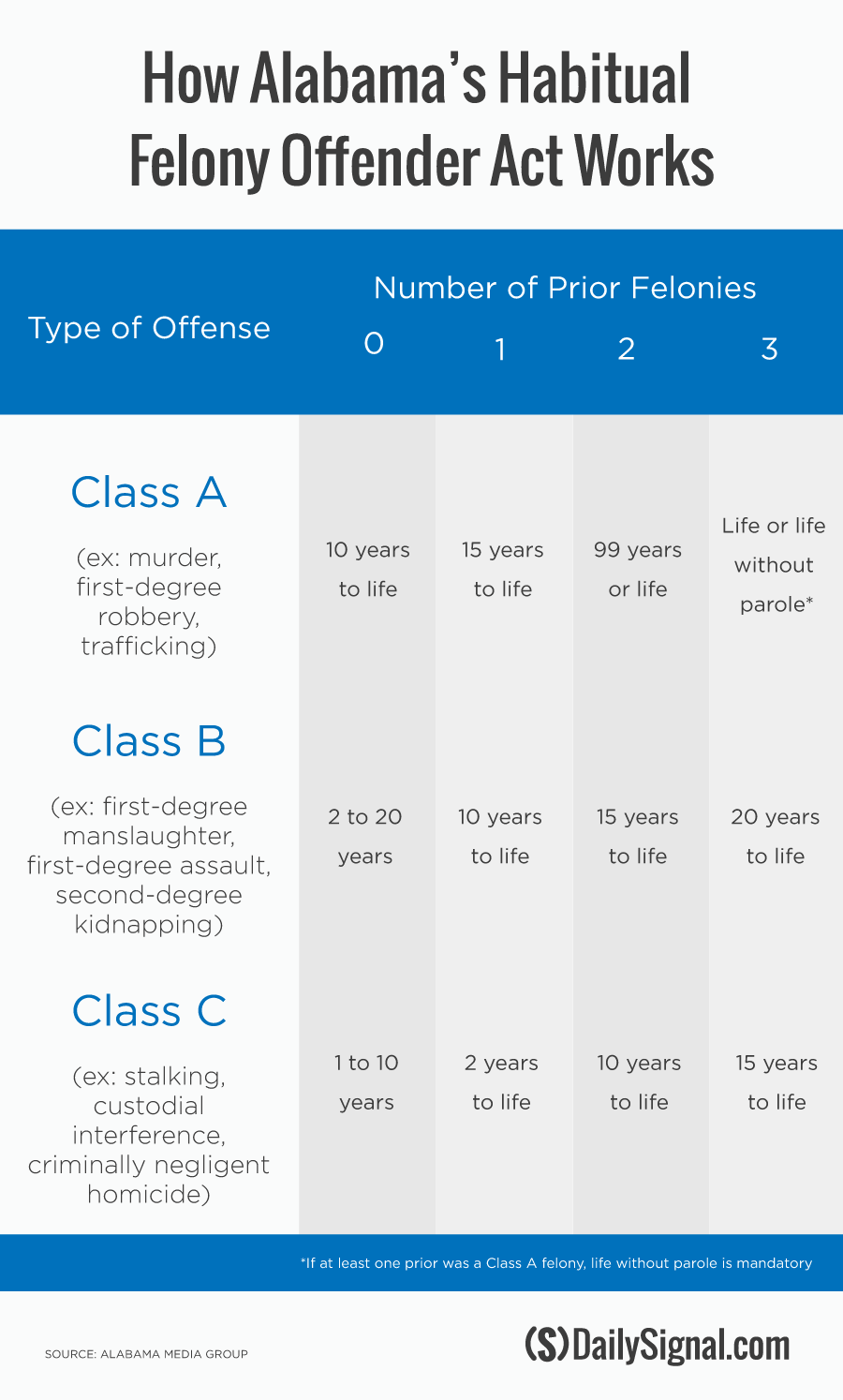

Many officials in Alabama blame the glut of nonviolent inmates on a 1977 state law called the Habitual Felony Offender Act.

At the time, the prison population was 3,455, according to the Department of Corrections.

From 1977 to 2013, the prison population increased by 840 percent, to 32,467.

Over lunch across the way from their courtrooms, three judges on the Jefferson County Circuit Court discuss their frustrations with the 38-year-old law, passed when nationwide fear over repeat criminal offenders was high.

“I think it’s the root of the problem [of prison overcrowding],” Judge Tommy Nail says.

Nail has overseen criminal cases in Birmingham since 1999.

He worries that the reform effort does not do enough to address “unfairness” in sentencing.

“One thing legislators are scared to death of is being accused of being soft on crime,” Nail says. He adds:

The first thing we should do is abolish the Habitual [Felony] Offender Act and have total sentence reform. But that’s not going to happen. It’s going to be a piecemeal process—take away this little bit and that little bit to try and avoid dealing with it head-on.

If you are convicted of a felony, the statute—popularly known as the three-strikes-and-you’re-out law—imposes additional prison time for prior felony convictions.

The law does not take into account the severity of prior offenses.

So if you are convicted of a Class C felony and already have three prior felonies—no matter what they are—you must be sentenced to 15 years to life in prison.

“It was never designed to go after the nonviolent, the drug-possession crimes, the petty thief,” Ward says of the law.

“It was designed to go after a committed murderer, or someone who molested somebody three times. But what happened was it evolved into a catch-all for everybody.”

Judging the Harshness of Sentences

The 1977 law also failed to deter offenders from committing new crimes, and Wright believes that is not by accident.

“It was premised around the fact that if someone were to keep committing crimes, they would be punished more harshly for subsequent actions,” Wright says:

I would say the knock against that is that it assumes people are thinking rationally or logically like you or I do. For someone who is addicted to drugs or has other mental health issues, they probably aren’t thinking about the legal ramifications of committing another criminal act.

Judges also complain that the Alabama legislature has been overly harsh in categorizing certain less serious crimes as felonies.

In Alabama, it’s a felony to unlawfully possess any amount of a controlled substance—even a single prescription pill that doesn’t belong to you.

If you’ve been convicted once for misdemeanor possession of marijuana, and you possess any amount of the drug again, that becomes a felony.

Theft of goods worth more than $500 is a felony. Such a felony threshold is near the lowest in the country. (South Carolina recently made it a felony to steal anything valued at over $2,500.)

Making Alabama’s sentencing even tougher is that all types of burglaries are considered violent crimes.

About 10 percent of annual prison admissions are for third-degree burglary, where the offender doesn’t encounter anyone while committing the crime. The reform bill establishes that third-degree burglary can be deemed violent or nonviolent depending on the circumstances.

“This is another popular political mechanism to appear tough on crime,” Circuit Judge Stephen Wallace says. “We have not really looked at classifying what is really violent and what is really nonviolent. Because there is no political will to really look at that.”

‘Alive’ but Weakened

Two years ago, as Judiciary Committee chairman, Ward helped Alabama adopt new sentencing guidelines meant to relieve prison overcrowding.

Judges must follow these “presumptive” guidelines, as they are known, when sentencing those convicted of nonviolent crimes unless there are aggravating or mitigating factors.

An aggravating factor—for example, the offender belongs to a gang or the victim is particularly vulnerable—could allow a judge to depart from the guidelines and impose a harsher sentence.

Mitigating factors—perhaps the defendant has mental health problems or a good support system—could permit a judge to give a more lenient sentence.

The guidelines are applied for theft and property crimes and most drug offenses, not for violent offenses such as murder and assault. It means that judges “no longer have complete and utter discretion to sentence how they want to,” the Sentencing Commission’s Wright says.

A judge must use a worksheet to calculate whether an offender should be sent to prison. The worksheet assigns points for various factors, such as previous convictions, and uses those points to determine whether the offender goes to prison and for how long.

The higher the point total, the harsher the punishment the judge must dispense. Unless an aggravating factor is proven, those sentenced using the guidelines cannot be punished as a habitual offender.

Creation of the least serious Class D category under the reform legislation builds on the work of the guidelines.

Someone convicted of a Class D felony automatically could not be sentenced using the habitual offender law.

In addition, for someone with a Class D conviction in his past, that crime cannot be used to enhance a sentence later if he commits another offense.

“The habitual offender law is still alive, but for a lot of crimes it’s a lot more difficult to sentence somebody as a habitual offender [under the reform bill],” Wright says.

Proponents of the guidelines credit them for reducing the number of convicted felons going to prison.

The problem: The number exiting prison didn’t drop at all.

“That was a great setting of the table for the reform discussion,” Wright says. He explains:

Because logically, you think, if we are reducing the number going to prison, shouldn’t the prison population be falling? We are sending fewer people to prison, but the people in there are serving longer periods of time.

‘Rat on a Wheel’

Not everyone is a fan of keeping more convicted criminals out of prison.

Blount County District Attorney Pamela Casey, a former three-sport star in her early 30s, is perhaps an unlikely face among opposition to the reform effort.

But Casey argues that the presumptive sentencing guidelines—meant to give nonviolent offenders the opportunity to better themselves outside prison’s unforgiving walls—actually lead to more crime.

“It’s very frustrating to think you are like a rat on a wheel, going around constantly,” Casey says.

The prosecutor says she has four or five cases on the docket involving prior offenders who could not be sentenced to prison under the guidelines, and have committed new crimes.

“Here’s the thing: I get irked when people say drug crimes are nonviolent offenses,” Casey says, adding:

The majority of violent offenses are the result of drugs. So, under the guidelines, you are not sending somebody to prison. Instead, they do probation, they don’t fix the drug problem, and two to three years down the line, they are a full-blown addict. Crimes escalate, they are stealing stuff, breaking into houses. And what happens if your 89-year-old aunt is in the house?

Of course, the idea behind the guidelines is not to let lawbreakers off the hook.

If a judge can’t send an offender to prison, he can sentence him or her to jail, community corrections, or probation.

Residents do laundry duty at the Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility, a privately run medium-security prison in Columbiana. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

The prosecutor and defendant also can agree to a plea deal allowing for the offender to be diverted to drug or mental health court.

In these specialized courts, participants get treatment and must appear before a judge who tracks their progress and can get tougher if they fail.

Depending on the locality, someone who successfully completes drug court can have his case dismissed.

Casey welcomes these alternatives, but she doubts their effectiveness without the threat of prison:

I want to be very clear. I am not against drug rehab, I am not against drug court, or people getting help with addictions. But I think the guidelines prolong the situation where they could be helped but aren’t, because the person thinks, ‘I’m not going to prison anyway, so why should I participate?’

Casey contends that offenders unwilling to better themselves end up on probation and without drug treatment.

She labels as onerous the process for seeking aggravating factors, which allow a judge to go outside the guidelines and choose prison.

She believes in prison so much that, back when the guidelines were voluntary, she never used them.

Committing to Community Treatment

Reform advocates say they understand Casey’s worries.

“But this contention that the guidelines magically close the prison doors—that if you pick up a drug case or basic theft case, you would need all sorts of prior convictions to get to prison—is just incorrect,” says Barbee, the Council of State Governments research manager.

He says the judge can revoke probation for those convicted of another crime and sentence them to prison.

And proponents designed the reform bill to contain cures to the ills causing recidivism.

“I think Ms. Casey’s concern is one underpinning the reform effort,” says Wright, the Sentencing Commission director.

Wright is referring to the fact that the reform legislation doubles the $5.5 million currently designated annually for community corrections and provides another $8 million for mental health and substance abuse treatment.

A resident brushes his teeth at the Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility, an alternative prison that strives to ‘break the cycle of recidivism.’ (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

Today, community corrections programs exist in only 45 of 67 Alabama counties. Many counties don’t have accredited programs to treat drug abuse.

“The absolute bottom line is that the state needs a lot more available substance abuse and mental health treatment,” Wright says:

If someone has a mental health or substance abuse problem, they absolutely need treatment. If the state continues to incarcerate people who have those needs, once they leave prison you haven’t really solved anything.

If the result is recidivism, Casey has a solution. “Instead of spending more money on studies, we should be building prisons,” she says.

If that doesn’t work, there are worse things than overcrowding, the prosecutor argues.

“I’ve been inside prisons; I know they’re crowded,” Casey says, adding:

But we’ve had four murders [in Blount County] the last 60 months, and you can tie them all back to drugs. That’s a big deal for my small county. People are breaking into houses, selling dope and not going to prison. How do you tell someone that because there’s not enough beds, these people will be loose in the community?

Not If, but When

Jeff Dunn, Alabama’s new Department of Corrections commissioner, is the man who manages the prison beds.

Dunn came to criminal justice straight from the Air Force, with no related experience. Armed with $60 million in bond money earmarked to add 1,500 to 2,000 prison beds, he could help feed more convicts into the system.

But Dunn, who is seeing the inside of prisons for the first time after beginning the job in April, views incarceration cautiously.

“One of the most startling stats I became aware of when I took this position is that 85 percent of those that are in our facilities now are going to return to the community,” Dunn says. “So the question is not if. The question is when and in what condition.”

Jeff Dunn, commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections, works in his Montgomery office. Gov. Robert Bentley appointed him in April. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

Dunn, 50, is a Birmingham native, but he’s really an outsider.

In his 28 years in the Air Force, he flew planes in the Iraq and Persian Gulf wars.

His experience allows him to look at prisons with a life-or-death perspective.

As the boss of Alabama prisons, his job is not only to keep the public safe by securing criminals, but also to ensure that the prisoners will be able to exit his facilities and productively re-enter society.

“From the very beginning, my professional career was all about service,” says Dunn, whose war medals neatly color his office. He explains:

With the Air Force, it was service to country. This is simply an extension of that service. Me and my staff understand and believe that this is a public safety mission. It’s vital to the state. It’s not something people think about a lot.

Dunn believes that the Department of Corrections is failing at its mission.

A map stuck to a wall in his office shows the locations of Alabama’s 31 prisons. By the end of summer, he plans to visit them all to evaluate their viability and to talk to wardens and officers about their vision—and his.

Some ‘Wicked’ Issues

Collectively, the state prisons are staffed at 62 percent to 65 percent of what they should be, based on the number of inmates in the system. The oldest prison was built in 1939.

A female-only prison is under federal order to reform itself because inmates have endured sexual assault by correctional staff.

A Justice Department investigation found that more than 900 prisoners inside the maximum-security Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women in Wetumpka, Ala., lived “in a toxic environment” where they were raped, sodomized and forced to engage in oral sex.

The reforms, among other things, require the prison to replenish low staff levels, especially of female officers, and to train staff to detect and respond to sexual abuse. The Corrections Department also hired a deputy commissioner for women’s services tasked with implementing the changes at Tutwiler.

“The issues in the prisons are long-term and systemic,” Dunn says:

These things have been building for many, many years. When you have a really tough problem or a thorny issue—in the military, we used to call them wicked issues—it’s a benefit to have a fresh set of eyes to view things from a little bit different perspective. I can question a lot of the assumptions behind why we do what we do.

When Dunn does the job of running prisons, he thinks of words such as “professionalism,” “integrity” and “accountability.”

Positive messaging adorns the corridor walls at the Alabama Therapeutic Education Facility, a prison intended for those in the final stages of a sentence. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

He sits on an implementation task force charged with proposing the next wave of criminal justice reforms for the legislature to consider, because, he says, the measure that was passed is not a “one-and-done thing.”

After the shock of the changes settles, Dunn wants to modernize his facilities.

He hopes to build new-generation prisons while eliminating facilities that don’t meet “safe and humane” standards.

A modern prison, Dunn says, would avoid the linear design of traditional facilities, where corrections officers can observe cells only one at a time.

Instead, a modern prison would feature a central pod, manned by officers who can observe and interact with each inmate in cells around them.

“So with a modern St. Clair, a modern max-security facility, you can achieve the same levels of security with less staff,” Dunn says, adding:

And over time, you could actually increase the ratio of prisoners to guards but still be able to do so safely and effectively. Because while no one is talking about releasing violent criminals, we still have a constitutional responsibility to provide safe and human care.

‘Just Want to Come Home’

Back at St. Clair, humanity is challenged.

During a reporter’s walk through a cell block, no corrections officers are visible, although Estes, the warden, says each block can house 192 prisoners.

This is a “faith-based” residence reserved for well-behaved inmates who have vowed to pursue religion.

The two-story living quarters look like a low-end dormitory.

The cell block is divided into rooms with two inmates each.

Instead of living behind bars, the prisoners share a tiny room, complete with two skinny beds, a small window and a toilet without a seat.

The inmates take pride in their home. One sweeps the floor of his room. Others cautiously stand straddling the entrance to their room and the hallway, as if to watch for intruders. They are probably right to be skeptical. Some of the locks meant to secure cell blocks do not work.

On the bottom floor—the community living space—a designated prayer area features a shelf of Bibles and other books.

Nearby, inmates wearing massive, out-of-style, over-the-ear headphones listen to FM radio and watch television. They choose from 13 channels, plenty for a prison populated by men born before the age of DirecTV.

“Most of these inmates are older, so they just want to do their time, and for those with the chance, to come home,” Estes says:

So most here are well behaved. Are there a few bad apples? Hell, yeah. It’s still a prison. It’s not peaches and cream. There are some who do things you don’t want them to do. But 10 percent of inmates cause 90 percent of my problems.

The prisoners say goodbye to their visitors.

“Come back and see us again soon,” remarks one man, sentenced to remain in prison soon, later on and forever.

Though Alabama’s criminal justice reform effort does nothing to help men and women imprisoned for violent crimes, St. Clair and other max-security prisons still will feel the changes.

If more nonviolent inmates never see a prison, and if the ones that do are released faster and under stronger supervision, the thinking goes, the expected easing of overcrowding will allow for smarter use of resources.

“The overcrowding issue is an umbrella that puts a shade over a whole bunch of other issues,” Dunn says. The corrections commissioner adds:

If we can relieve pressure in that sense, then you can make strategic decisions about your programming, about your facilities, about your manning levels. The way it touches St. Clair is if I can reduce that population of nonviolent offenders, I’ve just freed up security staff that I can apply at St. Clair. Which has the double benefit of decreasing the rates of violence.

Throwing more hands at the problem may help.

But to truly serve justice, Dunn and like-minded officials say, the state of Alabama must do it safely, fairly and effectively.

“I envision an institution that is nationally recognized for its ability to classify an inmate appropriately and get them into a course of programming that gives them the best chance at life success once they leave our facilities,” Dunn says. “That’s what criminal justice should be all about.”