Why Does America Love Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Loathe Clarence Thomas?

Elizabeth Slattery /

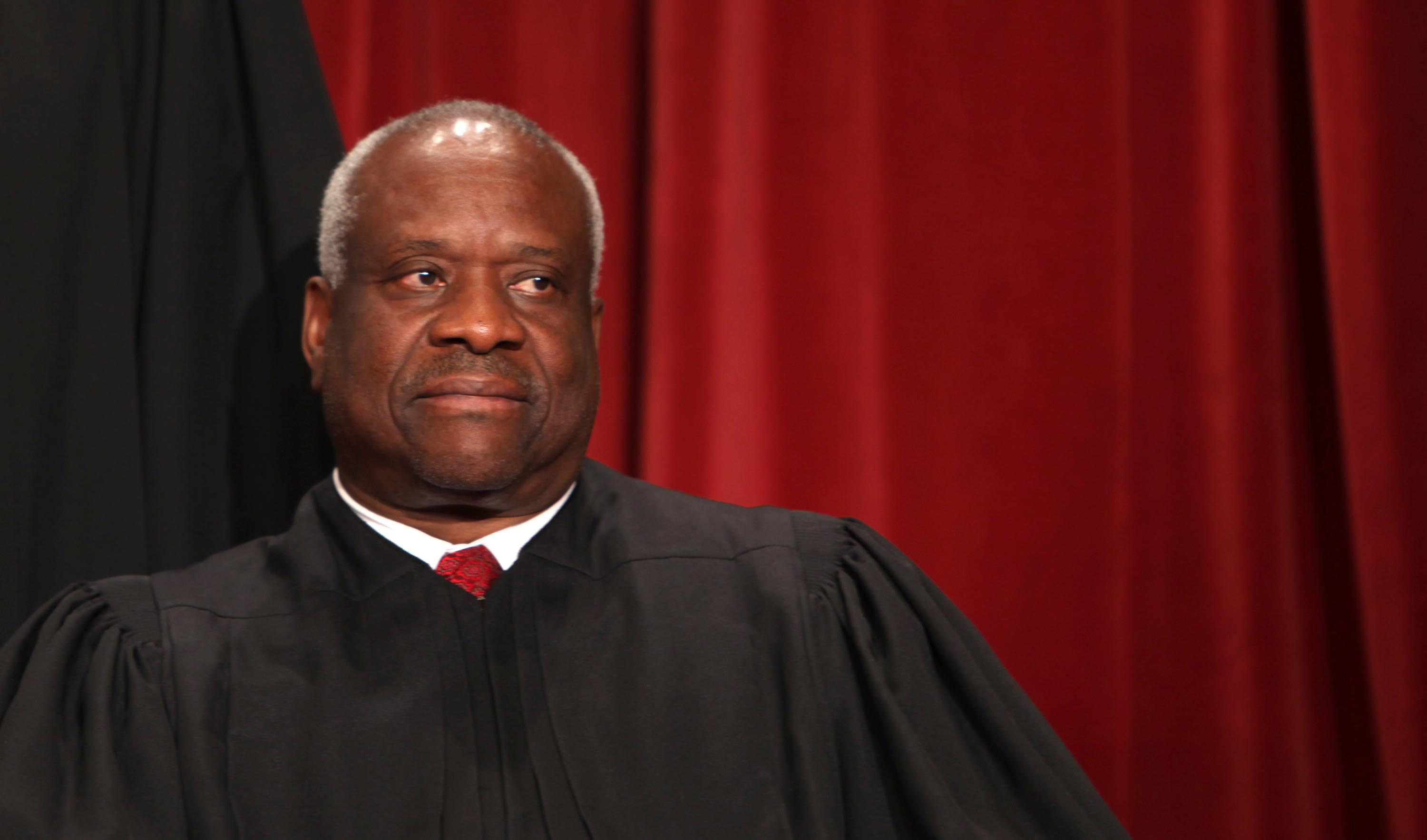

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is the most popular Supreme Court justice, while Clarence Thomas is the least liked, according to a new poll.

A June Public Policy Polling survey found only 35 percent of registered voters have a favorable opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is the Americans’ “favorite Supreme Court justice—to the extent that they have one” and Clarence Thomas is their least favorite, with 19 percent of voters choosing Ginsburg as their favorite and 18 percent choosing Thomas as their least favorite justice.

Why do Ginsburg and Thomas evoke such strong feelings?

Ginsburg became the second woman to join the Supreme Court when President Bill Clinton nominated her in 1993. She had served for thirteen years as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Prior to her career as a judge, she was a law professor and, as her colleague Antonin Scalia described her in Time Magazine’s 2015 “The 100 Most Influential People,” she was a “leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women’s rights—the Thurgood Marshall of that cause.” With the departure of John Paul Stevens in 2010, Ginsburg now enjoys the most senior position on the liberal wing of the Court.

In recent years, the “Notorious R.B.G.” has become a sort of pop-culture icon. Known for her signature jabot and fishnet gloves, Ginsburg has inspired t-shirts, blogs and even one woman’s tattoo. Natalie Portman will play Ginsburg in an upcoming film about the justice’s life and career, and “Saturday Night Live” introduced a Ginsburg character with the catchphrase “Ya just got Ginsburned!” Ginsburg has joked that her law clerks had to explain to her the Biggie Smalls origin of her nickname.

While Ginsburg is celebrated by the liberal media, the academy and now in pop culture, Thomas unfairly inspires anger, name-calling and questions about his intellect and fitness for the job.

Ginsburg has sparked controversy for publicly commenting on a range of hot-button cases that are pending in the federal judiciary—from Texas’s abortion law to same-sex marriage—drawing calls for recusal in high profile cases. Likewise, she made headlines last summer by chastising her male colleagues for having a “blind spot” on women’s issues. She has fended off calls for her retirement, pointing to Justice Louis Brandeis’ service until age 82 as a benchmark. But at 82, Ginsburg seems to be exactly where she wants to be.

Clarence Thomas also served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit before President George H.W. Bush nominated him to the Supreme Court in 1991. Earlier in his career, he served as chairman of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and as assistant secretary for civil rights in the U.S. Department of Education. Thomas is the second African American to have been appointed to the Supreme Court (after the legendary Thurgood Marshall).

While Ginsburg’s star is rising, Thomas has endured negative publicity beginning with his contentious confirmation hearings, which HBO will document in an upcoming film starring Kerry Washington. For the most part, Thomas avoids interviews and many speaking engagements, preferring to spend his downtime traveling around the country in an RV with his wife Ginni and following NASCAR and the Nebraska Cornhuskers.

On the bench, Thomas is well known for rarely speaking during oral arguments, unlike his colleagues, who often bombard advocates with questions. His last recorded statement at oral argument (which was an aside and not an actual question) was more than two years ago, when he made a joke at the expense of Yale, his alma mater.

Thomas has explained that he views oral argument as “an opportunity for the advocate, the lawyers, to fill in the blanks, to make their case … I think you should allow people to complete their answers … I find the coherence that you get from a conversation far more helpful than the rapid-fire questions.” He would rather be known for listening than lobbing questions.

Last year, The New Yorker published an article (“Clarence Thomas’s Disgraceful Silence”) in which Jeffrey Toobin insolently proclaimed that Thomas is “simply not doing his job.” This, despite the fact that Thomas has authored almost twice as many opinions as several of his colleagues in this term alone (seven majority opinions, seven concurring opinions, and sixteen dissents).

While Ginsburg is celebrated by the liberal media, the academy and now in pop culture, Thomas unfairly inspires anger, name-calling and questions about his intellect and fitness for the job.

What explains this disparity between the Notorious R.B.G. and Quiet Clarence? While Ginsburg fits the mold of a trailblazing feminist lawyer and her jurisprudence delivers on liberal expectations, Thomas defies stereotypes based on his upbringing and skin color.

Though he came of age in the heyday of the Civil Rights movement, helping organize the Black Student Union at his college and even supporting Malcolm X and the radical Black Panthers, and spent much of his career before joining the bench steeped in civil rights issues, as a judge, Thomas strives to advance the Constitution as it was written and originally understood, rather than a race-based agenda.

Whether that means voting to strike down part of the Voting Rights Act and ruling against affirmative action in state schools (pleasing many conservatives) or rejecting mandatory minimum sentences (pleasing many liberals), Thomas is willing to strip away layer upon layer of previous Supreme Court decisions to get back to first principles—to the ire of many on the left. Now who’s notorious?

Joining the Supreme Court hardly seems like the path to notoriety and fame, though it has been for Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Clarence Thomas. The public clearly has an appetite for information about the justices. Just consider the growing movement to allow cameras into the courtroom, or the sales records for The New York Times best-selling memoirs of Sonia Sotomayor, Clarence Thomas, and former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

This curiosity about the justices is heartening—but only if it translates to an interest in understanding the proper role of the judiciary, and not yet another effort to cast the justices as politicians by another name.