King v. Burwell in Perspective: Only 1 Out of 5 Whose Insurance Costs Grew Because of Obamacare Got Subsidies

Edmund Haislmaier /

The Supreme Court will soon hand down its decision in King v. Burwell. That case asks the court to decide if the statutory text of the Affordable Care Act authorizes the Treasury to pay subsidies to individuals who purchased coverage through HealthCare.gov—the federally operated health insurance exchange for states that did not establish their own exchanges.

Yet behind the legal dispute over who is eligible to receive subsidies lurks the larger policy issue of the subsidies’ function. While their stated purpose was to help more low-income individuals purchase health insurance, the subsidies also served to mask the significant health insurance premium increases that would inevitably result from the law’s new insurance benefit requirements and regulations.

For instance, if a 45-year-old received $540 annually in subsidies, he may not realize that the premium for the lowest-cost health insurance plan in his area actually had increased by $600 a year thanks to Obamacare regulations—because the government was paying most of that additional cost.

That imposition of costly new requirements on health insurance coverage was one of Obamacare’s fundamental errors. Good health care policy, by contrast, would have started by focusing on finding ways to make coverage less costly rather than just having the government pick up some or all of the extra cost.

Furthermore, the design of the subsidies also created one of the Affordable Care Act’s biggest inequities. Namely, the number of people getting the new subsidies is only a small subset of the much larger number of people whose coverage is subject to the law’s new requirements that drove up health insurance premiums.

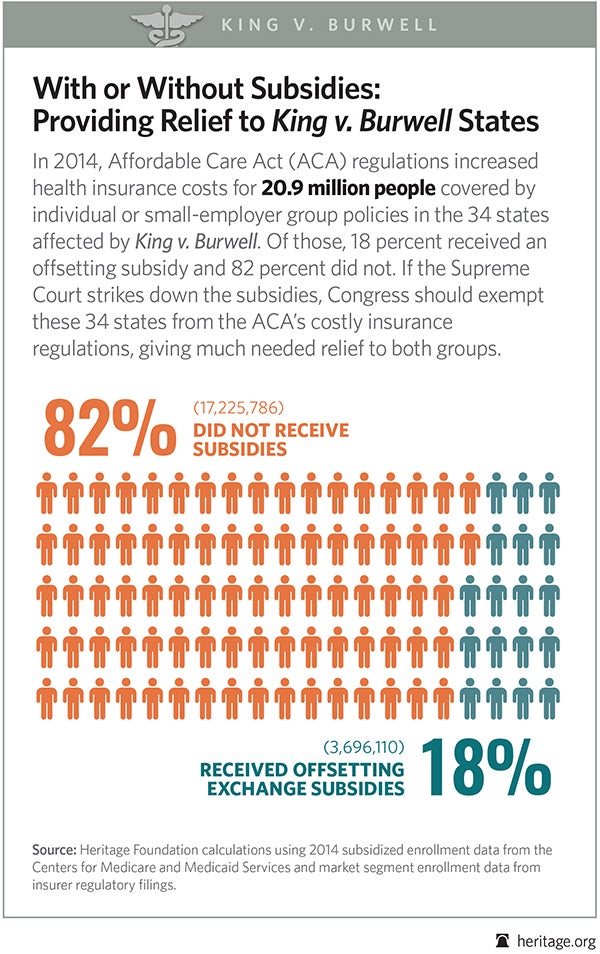

To illustrate, this chart shows the 2014 figures for total enrollment in individual and small-employer group (50 or fewer employees) health insurance plans—the plans subject to the most costly Affordable Care Act insurance requirements—and the subset of those individuals who received offsetting subsidies through HealthCare.gov, in the 34 states affected by King v. Burwell.

For those 34 states collectively, only 18 percent of enrollees subject to the Affordable Care Act’s cost-increasing insurance requirements received subsidies last year to offset those higher premiums. Put another way, for each person who got a subsidy last year, there were four more individuals whose coverage was also subjected to the Affordable Care Act’s costly new insurance requirements, but who received no offsetting subsidy.

Should the Supreme Court rule that the subsidies were improperly paid in those states, Congress should respond by helping bring the cost of health insurance back down by exempting both those with and without subsidies from the Affordable Care Act’s costly insurance requirements.