Labor Pains: Why the Birth Rate Is Down and What That Means

Madaline Donnelly /

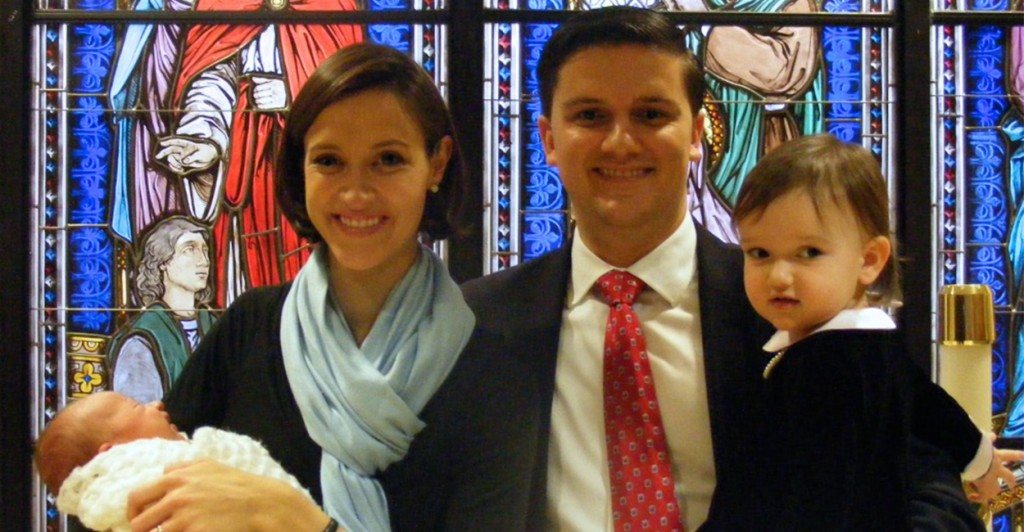

When Maria Harrill was growing up in suburban Maryland in the early 1990s, she kept a journal outlining all the things she’d do when she was a mom.

She attentively monitored her own family of 10 and—more like a discerning social worker stopping by for a visit than the second youngest of a brood of eight—noted things she liked, and disliked, about her household.

Today, the journal reads like a time-capsuled to-do-list for the 26-year-old mother of two: “Always read to your kids,” for example, is scribbled down next to “Never argue in front of the children.”

“I should go back and read it all, see how I’m living up to my own standards,” the former paralegal says with a laugh.

It’s clear that Maria wanted a family of her own from the get-go, and that she’s comfortable owning her choices. It’s also become increasingly clear that her story, of growing up in a big family and wanting to replicate that for herself at an early age, is no longer the norm for a majority of young American men and women.

We see this play out on television and in the movies (think “Girls” or “Wedding Crashers”). We hear it in graduation speeches lauding endless opportunities and paths. And then there’s the data, painting a picture of career-driven millennials who are the slowest to have kids of any generation in U.S. history.

But what, if anything, do these changing norms mean for those couples that still choose to start families young? For society at large?

A New Normal

There are many factors potentially at work today discouraging young people from having children that it’s hard to know for sure what’s really behind the dip in America’s birth rate—or to blame for holding off.

Between the Great Recession, the necessity of a college education (and therefore, the magnitude of student loan debt in the U.S.), the price of homeownership, and delayed marriage due to social or financial reasons, it seems more a storm of inhibiting issues than an identifiable trend.

Some younger moms also theorize about the both assumed and realistic social implications of motherhood, and its ability to deter young women from having kids.

“Some of my friends are getting engaged, but they have no plans of having babies until much later on,” says Suzanne Kioko, a 26-year-old registered nurse and mother currently expecting her second child. “They have this notion of life is kind of going to suck as soon as you have kids. And they want to get in all their good times before they [have children].”

Regardless of its cause, we do know that the birth rate drop is meaningful. Just last month, the Urban Institute published a widely circulated paper outlining a 15 percent decrease of American women in their twenties having children. Previously, the birth rate was largely stable for this demographic from the 1980s until around 2007.

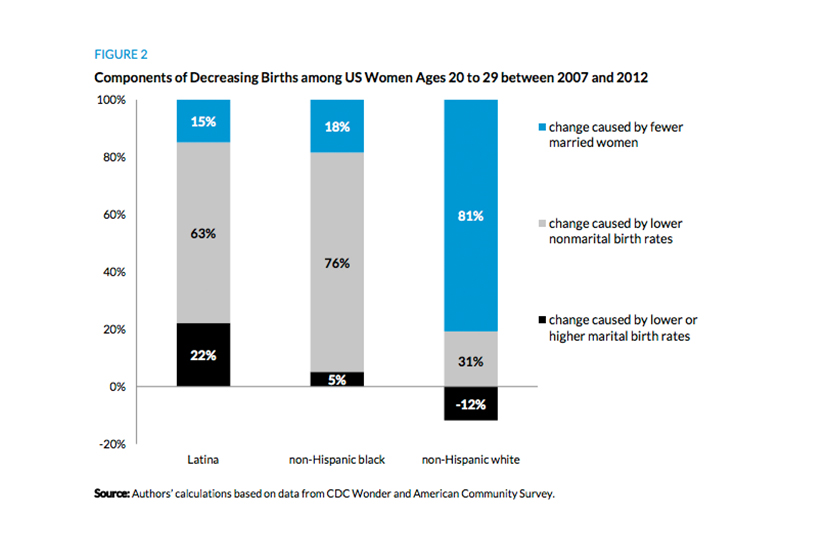

Researchers Nan Marie Astone, Steven Martin, and H. Elizabeth Peters authored the study and found that birth rates to women aged 20 to 29 fell, dropping from 1,118 in 1,000 women to 948 in 1,000 women in 2012. Simultaneously, strong immigration rates which would have helped to supplant such a decline dipped, likely because of the struggling economy.

Worth noting, all races experienced a decline in giving birth, with the largest drop being seen among Hispanic women. For white women in particular, the birth rate decline was linked directly to a marital decline.

“Marriage has come a capstone to adulthood, rather than an entryway into adulthood as it has traditionally been,” says Rachel Sheffield, a policy analyst with The Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity. “Today, individuals often wait to marry until they have achieved a level of independence marked by completing college, establishing a career, and perhaps even having already purchased a home.”

It’s too early to tell whether these young women will “match” previous generations by having babies in their 30s or later. Historically speaking, the birth rate also fell in the early 1930s and late 1970s, aligning with other periods of economic struggle, before bouncing back and evening out.

“If these low birth rates to women in their twenties continue without a commensurate increase in birth rates to older women,” the Urban Institute researchers wrote, “the United States might eventually face the type of generational imbalance that currently characterizes Japan and some European countries.”

Much Ado About … Something?

So what do these “warnings” really amount to? According to Jonathan V. Last, a senior writer at The Weekly Standard and author of “What to Expect When No One’s Expecting,” America is facing a “demographic cliff,” or a population replacement rate that simply isn’t sustainable, as he wrote in “The Wall Street Journal.” In his opinion, population-dependent programs like Social Security—along with tax-dependent organizations like the military—could suffer.

“Decline isn’t about whether Democrats or Republicans hold power,” he writes. “It isn’t about political ideology at all. At its most basic, it’s about the sustainability of human capital.”

Last goes on to cite social and economic problems in countries like China, Japan, and Mexico, tracing their origins to things like China’s infamous one-child policy or the overall decline in the marriage rate in Japan.

Anthropologists have also written about the economics of European nations like Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, blaming declining demographics and an inability to develop strong economies. In Russia, the government has offered monetary incentives for having kids, and in Denmark, independent organizations like travel-company Spies Rejser have launched campaigns asking citizens to “Do It for Denmark!”

Recently, 2016 presidential candidate Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., along with Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, proposed a tax reform plan that included a child tax credit.

In practice, lower birth rates probably don’t make a huge difference in the lives of young American mothers yet, outside of occasionally awkward conversations at work and a more difficult time making friends who are “in the same boat,” as Suzanne says.

“Nowadays, you don’t have a lot of younger moms having babies, so you kind of feel like you’re on your own,” she adds. “Most of your friends are still working and doing their thing, so socially, I think it’s changed.”

Maria agrees: “I remember I was working at a law firm downtown [in Washington, D.C.], and I was still working when I got pregnant. It was definitely weird. It was like a glance, or a look, or a comment, and you could tell that it’s, ‘Oh wow, you just got married and really, you want to start a family already?’”

Kassie Novak, a 26-year-old mother who lives in Chicago with her husband and 18-month-old son, has found that making friends with other mothers takes a significant amount of work because of the age difference.

“I do try to put an effort into meeting other moms. It’s much harder than I would have imagined,” she says. “Just about every mom I have met here is about five to 15 years older than me … I used to joke with my husband that I think the moms at the park or at baby classes think I’m the nanny. But now that my son is older, I am much more comfortable approaching and chatting with other moms.”

Dollars and Sense

Aside from shifting social realities, young families are also making fiscal sacrifices in order to afford a family, reflecting the estimated $250,000 it currently takes to raise a child in America.

And while the share of moms who did not work hit an all-time low in 1999 at 23 percent, it rose to 29 percent by 2012, according to the Pew Research Center. This group includes those who are unable to find work or disabled.

Suzanne, Maria, and Kassie, employed full-time before having their children, are all working in some capacity outside of the home, whether it’s picking up spare shifts at the hospital or selling skin care products in their free time, as is the case with Kassie.

“We’re renting an apartment,” Maria says of her Reston, Va., home. “All of our couple friends have been talking, and it looks like we’ll all be renting … for a while. Houses just cost a lot. Unless you have a really great paying job, it’s a little bit harder.”

Maria and her husband are also sharing one car. “Two would be awesome, but it’s not realistic right now,” she says. “But I’d much rather have another kid as opposed to another car. Kids are around a long time, but cars come and go.”

There are possible benefits for these families, though, including things like more open slots at schools and readily available vaccines. The Urban Institute study, using census data, also suggests a lower birth rate could potentially mean greater social mobility in the future for babies born to millennials.

In contrast, researchers found that among baby boomers and Gen Xers, “single parenthood increased among already disadvantaged groups,” and furthered income inequality between high- and low-income families.

In certain circumstances, a decrease in the birth rate could also mean more stable environments for children.

“As of 2010, the average age at first birth for a college educated woman was about 30, whereas in 1970 it was around 26,” Sheffield says. “Among those with less than a high school education, the average age of motherhood was about 18 in 1970, whereas today it’s around 20.”

For their part, the millennial mothers The Daily Signal spoke with seem content with their decision to start a family young.

“Being a young mom was what I’ve always wanted,” Kassie says. “I believe motherhood to be my calling.”