Why Giving Your Kids Siblings Is the Best Thing You Can Do for Them (Even If They Resent It)

Stephen Hayes /

Giving your kid a sibling is the best thing you can do for them, and as often as not, they resent you for it. My wife’s OB-GYN told us a story—in the middle of labor—about how he had welcomed his newborn brother to the family by burying him in a basket of dirty clothes and refusing, for hours, to reveal his whereabouts.

Very few things bring greater happiness than sibling harmony. But the inverse is also true: There are few things more irritating than listening to children bicker and few things more dispiriting than sibling-on-sibling violence. If war is the failure of diplomacy, then sibling fights feel like the failure of fatherhood.

Sibling rivalry is both eternal and natural. Things ended badly for the very first pair of siblings, Cain and Abel. Why? The usual reason: Because the older kid was jealous of the attention his parents lavished on his baby brother.

Siblicide is common among many species of birds and some mammals. Spotted hyenas, for instance, sometimes fight to the death for their mother’s attention. Cattle egret hatchlings often do the same, with older and stronger siblings killing younger offspring to ensure their own survival. If things get really tough, they sometimes have them for dinner.

With humans, it usually doesn’t go that far. But that hasn’t stopped people from studying the heck out of the problem. There are piles of research on virtually every aspect of sibling relationships—not to mention the laymen’s stuff in parenting magazines and websites and even on reality shows like “Nanny 911” and “Supernanny.”

At the heart of all of this is a simple question: How do I make my kids get along?

According to one book by two prominent child psychologists, parents can end fights between their children by channeling negative energy into “some form of creative expression.” They suggest that kids be given dolls or pillows and encouraged to release their anger onto those objects, rather than their brothers or sisters. Parents who are especially crafty—in the Michael’s, not the Machiavelli, sense—can intervene with “clay, finger paints, or crayon and paper as avenues of expression.”

If war is the failure of diplomacy, then sibling fights feel like the failure of fatherhood.

Maybe this works for some families. But in a fight between normal preteen brothers, the crayons are likely to become projectiles, the clay will be used to plug various orifices, and the finger paints just make it harder to figure out who’s bleeding.

So what’s the answer? It strikes me as more than a happy accident that I am extraordinarily close to my three younger siblings even as we approach middle age, and that my own kids—now ages 10, 8, and 5—are friends and not enemies. In other words, like everything else in life, it helps to have been born into a good family.

Growing up in suburban Milwaukee, my siblings and I were reasonably certain that we had the strictest parents on the block and that they were ridiculously tough because they wanted their kids to be losers. (In hindsight, the first part was true, but the second was not.) In high school, we had to be home by the time most parties were getting started.

When we were visiting friends in that pre-cellphone era, our folks would actually call ahead to make sure there would be parents at the house, which was unspeakably embarrassing, but not the worst thing they did to us in semipublic.

During a holiday break from college one year, my sister, Julianna, stopped at the local video store to rent “The Big Lebowski.” At the cash register, the clerk—a pimply-faced teenager—told my sister that she couldn’t rent it because her membership still had a parental block for R-rated movies.

Yet shared hardship—or even, in our case, a shared imagined hardship—forges strong bonds. And with nothing better to do, we spent our childhood years outside, together.

There were hours of cops and robbers, Wiffle ball, capture the flag, and driveway basketball, along with some now politically incorrect pastimes. Because our elementary school was a block away from home and had a skating rink from November to early March, there was hockey before school, on lunch break, and immediately upon afternoon dismissal.

It wasn’t as though we never fought. We did. And there were times I was the kind of mean only an older brother can be. I used to force my siblings to play not-entirely-safe games of basement football. I allowed my sister to opt out of offensive-line duty to be a cheerleader, if she wanted. (She claims that I once tied her to a pole in the basement and made her cheer for us. But I suspect this is apocryphal.)

Yet shared hardship—or even, in our case, a shared imagined hardship—forges strong bonds.

But I shared a bedroom with my little brother, Andy, for virtually all of my childhood. My parents didn’t know it at the time, but we stayed up until midnight almost every night. I had a clock radio with a flat, faux-wood top. After we did the dinner dishes we’d race upstairs to listen to whatever sport was on, usually the Milwaukee Brewers or the Bucks. I’d hide the radio under my pillow, and we’d listen and talk and then talk some more.

My sister, Julianna, shared the other bedroom with our youngest brother, Dan, and as we grew bigger the house seemed to grow smaller. I was a sophomore in high school when my folks decided that we needed more space. They expanded our kitchen and added a fourth bedroom. When the work was done, they broke the exciting news in separate meetings—with me first, and then my sister. Because I was the oldest, and because she was the girl, we would each be getting our own bedrooms.

We both refused. The new bedroom stayed vacant.

One of the great ironies of fatherhood is that for most of us it’ll be the most important work we do, but there’s virtually nothing we can do to prepare for it. There’s no way to show up for the first day of the job with any experience. So it’s natural to rely on the example of our own fathers—to emulate our dad if he was a good father and to learn from his mistakes if he wasn’t.

And hope that, at the very least, the kids don’t eat each other.

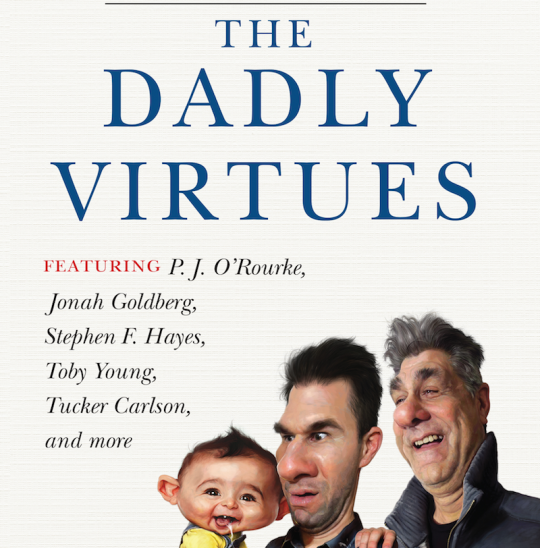

Excerpted from “The Dadly Virtues: Adventures from the Worst Job You’ll Ever Love,” edited by Jonathan V. Last and released today.