Even Cost-Benefit Analysis Misses the Overall Impact of Regulation

Norbert Michel /

In some cases, federal financial regulators have to consider the incremental impact of new rules and regulations. But they hardly ever are required to examine the cumulative effect of all previously implemented regulations.

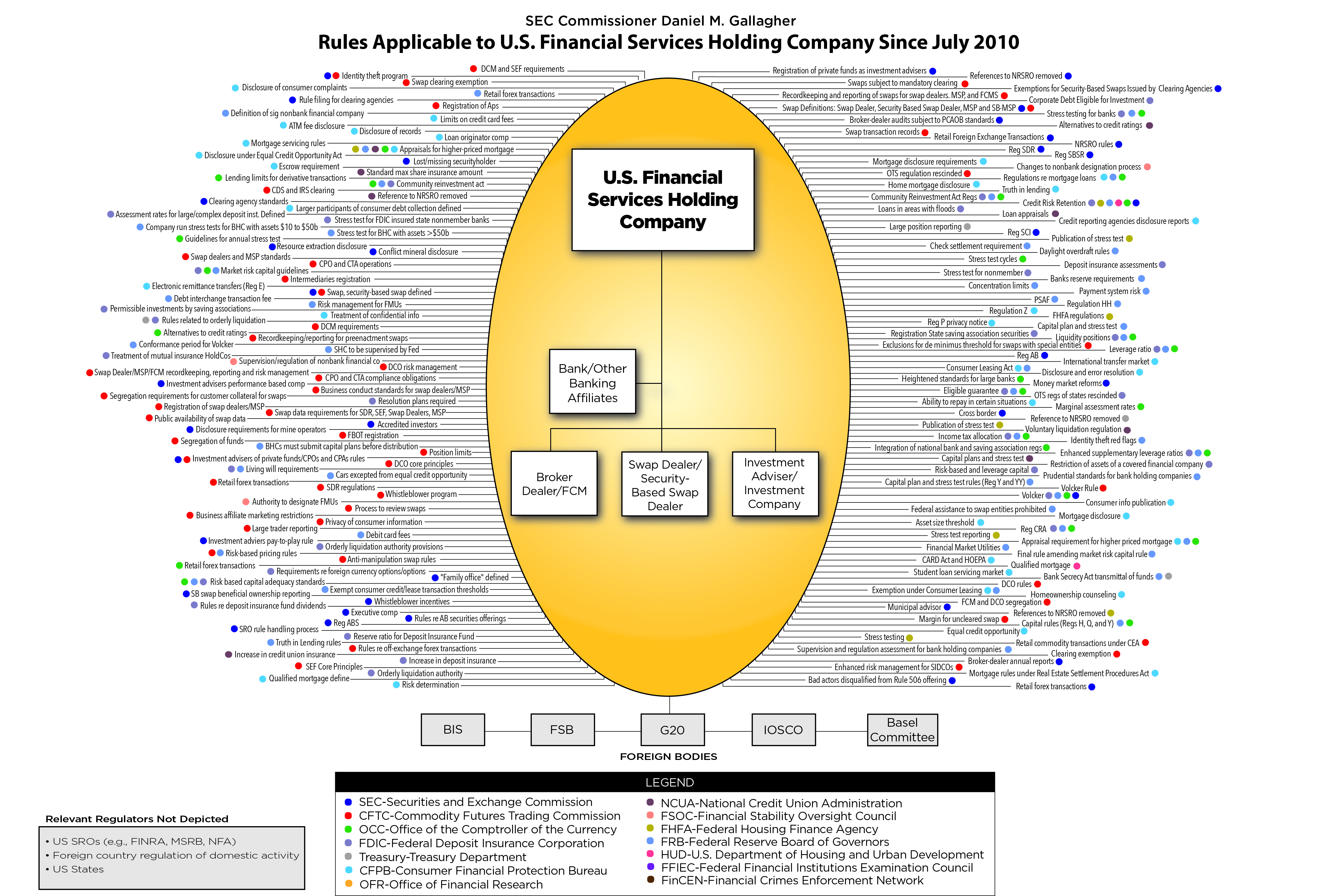

After decades of increasing federal requirements on financial firms, this weakness allows regulators to ignore an enormous burden on our capital markets. To paraphrase Securities and Exchange Commissioner Dan Gallagher, the cumulative weight of these regulations could soon culminate in death by a thousand cuts for financial markets.

To highlight the total burden of recent regulations, Gallagher’s office released a diagram of the rules implemented via the 2010 Dodd-Frank bill. As dramatic as this chart is, it provides a mere taste of how burdensome financial market regulations are. To begin with, roughly half of the newly required Dodd-Frank rules haven’t been completed yet.

Even worse, though, is the aggregate impact from all the rules prior to Dodd-Frank. For decades, financial firms have had to employ armies of lawyers and other specialists to comply with political mandates that distort our financial markets. Simply keeping track of all the rules has become a full-time job.

And any chart like this one merely identifies the recent additions by name—the actual statutory law is often dense and complex, and the separate rules and guidance are at least as bad as the statutes.

Each section of the U.S. Code refers to other sections, and practically every new law adds additional connections. Here’s just one example from Title 7 of the U.S. Code, a section that deals with the jurisdiction of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission. This section deals with the commission’s oversight in the market for swaps, a special type of financial contract.

(d) Swaps

Nothing in this chapter (other than subparagraphs (A), (B), (C), (D), (G), and (H) of subsection (a)(1),subsections (f) and (g),sections 1a, 2 (a)(13), 2 (c)(2)(A)(ii), 2 (e), 2 (h), 6 (c), 6a, 6b, and 6b–1 of this title, subsections (a), (b), and (g) of section 6c of this title, sections 6d, 6e, 6f, 6g, 6h, 6i, 6j, 6k, 6l, 6m, 6n, 6o, 6p, 6r, 6s, 6t, 7, 7a–1, 7a–2, 7b, and 7b–3 of this title, sections 9 and 13b of this title, sections 13a–1, 13a–2, 12, 12a, and 13 of this title, subsections (e)(2), (f), and (h) of section 16 of this title, subsections (a) and (b) of section 13c of this title, sections 21, 24, 24a, and 25 (a)(4) of this title, and any other provision of this chapter that is applicable to registered entities or Commission registrants) governs or applies to a swap.

So, nothing in this particular chapter applies to swaps, except for what’s in six different subparagraphs, 11 subsections, 44 sections and any other provision of the chapter that is applicable. For anyone who thinks all this is benign, here’s a fun game: Click through the above links and try to decipher all the exceptions in less than 24 hours (that’s how many work hours it took us).

Also keep in mind this paragraph is one tiny piece of the U.S. Code, tens of thousands of pages itself. Moreover, there are tens of thousands of pages of agency-generated regulations and even more voluminous “guidance.” Even though regulatory guidance is not binding, industry participants know unfortunate things happen to those who ignore it.

This mass of complexity has been building for years, and the notion Congress has done anything substantial to lower financial firms’ regulatory burden in the last several decades is absurd. Capital formation is the lifeblood of our economy, but the regulatory state we’ve built is slowly bleeding it to death.