Home Is Where the Heartache Is: Hurricane Sandy Victims Still Not Recovered

Josh Siegel /

EAST ROCKAWAY, N.Y.—For Frances Healy, a 90-year-old widow known as “Muzzy,” home is just a tease.

Muzzy lives so close to her gutted, molded home—an unhealed victim of a hurricane that hit nearly two-and-half years ago—that she can see it.

But she can’t live in it.

From her vantage point through a window in the trailer here in East Rockaway on Long Island in New York, she can see a home that, from the outside, looks the same before it met Hurricane Sandy.

It’s the same home that Muzzy and her late husband, Jimmy, built in 1947, transforming it from a “dump” to “heaven on Earth.”

But from the window of the trailer where she now lives, or from anywhere, what she can’t see is a way back into the home.

“It’s heartbreaking because there’s so many memories there,” said Muzzy, whose quiet, cracking voice belies a feistiness that showed itself when she playfully heckled a Daily Signal filmmaker for being too slow to get his equipment ready.

“We raised 10 children in this house,” Muzzy said. “We had so many memories in this house.”

This wasn’t supposed to be so hard—recovery.

“I know what I’m getting into living on the water,” says @krainsbo.

People who live on the water know the risks and insure themselves against them.

“I know what I’m getting into living on the water,” says Kathleen Besedin, whose dream home in Baldwin Harbour, N.Y., was severely damaged in Hurricane Sandy.

“I am not a stupid person. I know it can flood and that’s why I did everything right.”

When Hurricane Sandy barreled toward the East Coast in the fall of 2012, many, like Muzzy, who had to be dragged away by her family, didn’t think they’d even have to leave their homes.

No one could have expected how devastating Hurricane Sandy turned out to be: 117 deaths, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and more than $60 billion in damage, second only to Hurricane Katrina.

And no one could have guessed how the mechanisms set up to protect homeowners, and to refurbish them against future storms, would fail.

Responding to accusations that damage assessment reports were fraudulently changed to minimize claims, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has agreed to review every flood insurance claim filed by homeowners affected by Hurricane Sandy.

Those actions came in the wake of law enforcement inquiries and reports by The New York Times and CBS News program “60 Minutes” on widespread fraud by engineering companies supervised by FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program.

During a visit last month to Long Island, among the areas hardest hit by the storm, homeowners also spoke of problems related to a New York’s grant recovery program set up to fill the funding gaps left by their flood insurance and other forms of aid.

Launched in April 2013, New York Rising uses $4.4 billion in federal funding allocated to the state to help people rebuild their homes.

New York Rising is similar to other grant programs in New York City and New Jersey.

The programs were set up carefully.

After Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, widespread corruption and fraudulent claims marred the recovery.

To avoid similar problems in New York, the state created a program with a complicated application process.

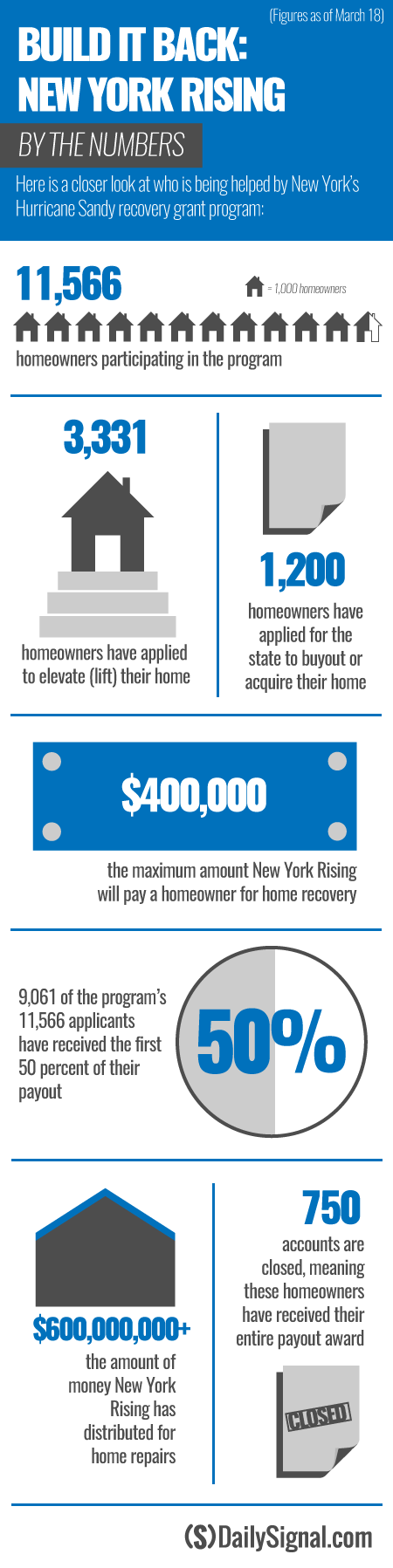

Though New York Rising has distributed more than $600 million for home repairs so far, some homeowners complain the program has moved too slowly, plagued by heavy-handed bureaucracy, excessive paperwork and constantly changing policies.

“Thank God for the grant program,” said Mary Shaw, a resident of Long Beach, N.Y., who decided to knock her home down and is waiting on money from New York Rising to rebuild.

“But it is a waiting game. It’s been longer than we ever expected to wait for help. You don’t want to complain. It’s a grant program. I just wish it were run better.”

Rep. Lee Zeldin, R-N.Y., represents a district in eastern Long Island. He works with New York Rising to make sure the program is helping people come home.

“It would be foolish not to revisit lessons learned to get it right the next time,” says @RepLeeZeldin.

“I think expectations from the get go—some people just assumed, as soon as Congress passed money, they would see a check, they would barely have to put in paperwork,” Zeldin told The Daily Signal.

“As far as efficiency goes, some of the policies … unnecessarily lingered too long. If another storm, God forbid, happened, it would be reckless, it would be foolish, not to revisit those lessons learned to get it right the next time.”

New York Rising officials say the program is working as well as could be expected.

They say they’re beholden to stringent guidelines required by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the federal agency that governs the distribution of grant money.

And they say they’ve made changes to the program in order to meet evolving homeowner needs.

For example, New York Rising recently adjusted its award payment formula for some people who are reconstructing their homes.

Instead of paying 50 percent of repairs upfront, and the other half upon completion of repairs, New York Rising will pay 50 percent at the outset, 25 percent after a “substantial” amount of work has been finished and the final 25 percent upon completion.

“I don’t want to sound like a bureaucrat, but I do think that there’s a responsibility here and a management of expectations,” said Barbara Brancaccio, a New York Rising spokeswoman, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“It’s the responsible monitoring of taxpayer dollars. You want to protect the funds. When you make changes like this, it’s to get more money to the homeowner, not to make it more difficult. It’s very hard when you’re in the situation to see the big picture. We work very hard to get as much money as absolutely possible into the hands of the people who need it.”

A walk through a Lindenhurst neighborhood shows how recovery does not look the same for everybody.

Ellen Huggins, the secretary of Adopt a House, a nonprofit founded to help rebuild Long Island communities after Hurricane Sandy, is leading the tour.

Huggins was fortunate enough to rebuild her home.

But visible through her front window is a grassy patch of land where a home once stood.

As part of New York Rising, residents have the option to participate in a buyout program, allowing the state to purchase the damaged property to raze the home and return the area to nature.

The state has bought about 1,200 properties as of mid-March.

Another home near Huggins’, a couple streets away, has seen no work. It looks, as if frozen in time, the same as it did after the storm—like a skeleton.

The walls of the back of the home have been blown off, to where you can see inside.

A swivel chair, probably an item that belonged to a former office space, and a trash basket, lay strewn in the melting snow.

“We want the neighborhood back,” says Ellen Huggins of @AdoptAHouse.

“My neighbors are gone,” Huggins said. “There are people who just left. There are people who are still struggling. And we want them to come back. We want the neighborhood back. I want my neighbors back. We’d like to see [New York Rising] be successful. We’d like to see the program achieve the goals it is setting out to achieve. We’d like it to assist people: to elevate, to reconstruct, to rebuild, to be safer —so that the neighborhood can continue to thrive.”

Muzzy won’t leave her neighborhood. It’s where she goes to church. It’s where her husband, Jimmy, hand-made the furniture that came to decorate her home, and then, be destroyed—erasing one of their enduring links.

“She’s lived in this town since she was 2. It’s where she wants to die,” says Kate Hughes, Muzzy’s daughter.

For Muzzy, home, so close but so far, is where the heartache is.

Asked where she wants to live, she points through the trailer window, “In that house.”