As Ukraine Tries to Purge Its Communist Past, Terrorist Threats Follow

Nolan Peterson /

KHARKIV, Ukraine—As fighting continues to escalate in east Ukraine, a pro-Russian separatist group calling itself the “Kharkiv Partisans” declared Tuesday that it would execute five Ukrainian civilians for every Communist monument destroyed, underscoring worries that a recent law banning Soviet symbols might escalate tensions in the war-torn country.

The threat followed a Monday meeting in Berlin between delegates from Russia, Ukraine, France and Germany to defuse the Ukraine conflict’s recent uptick in violence.

“[E]ach monument in Kharkiv equals about five Ukrops (a derogatory term for Ukrainians),” Kharkiv Partisans spokesman Filipp Ekozyants said in a YouTube video released Tuesday, speaking in both Ukrainian and Russian.

“Soviet soldiers will always remain heroes and liberators of Ukraine,” he added.

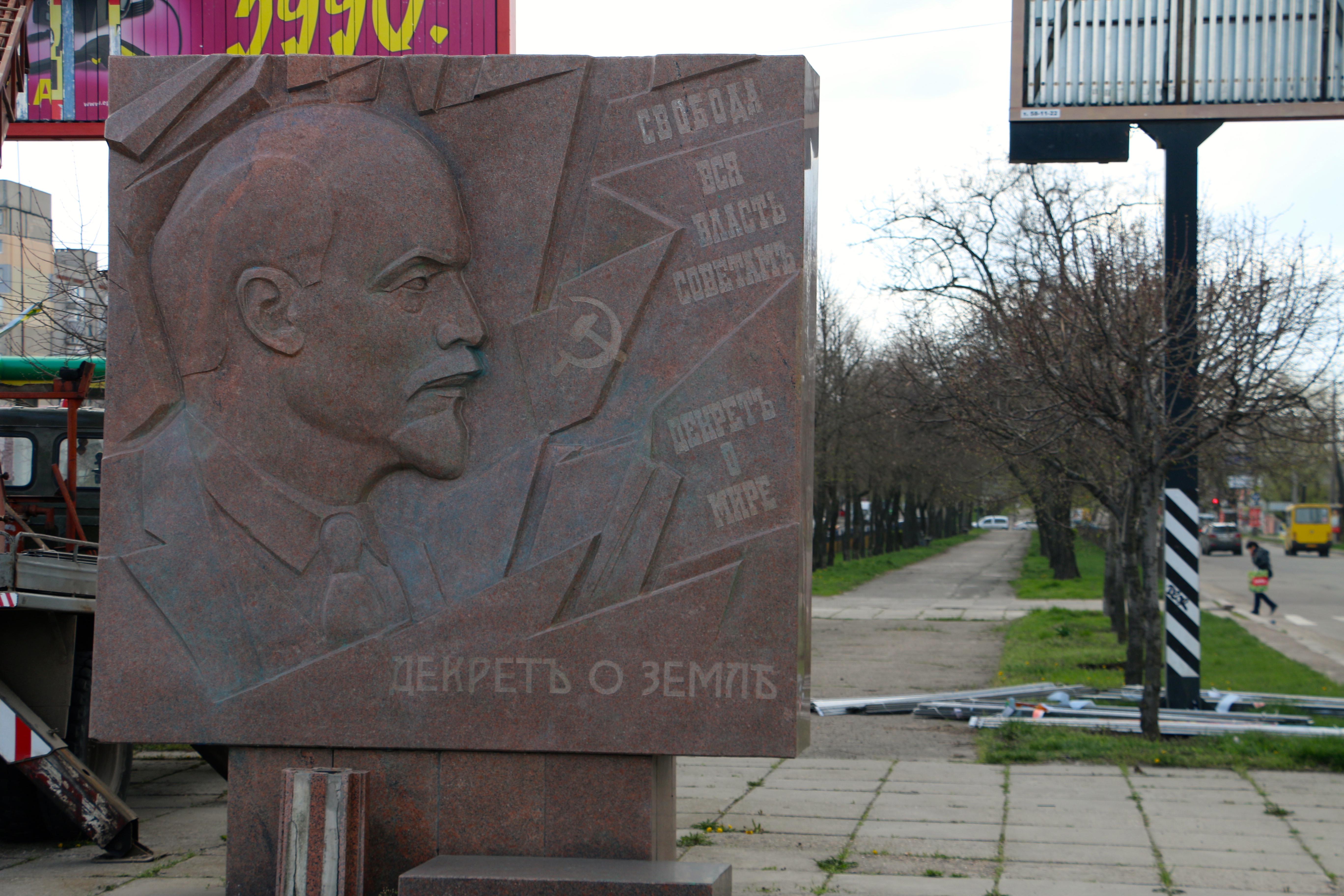

The militant pro-Russian group has previously claimed responsibility for a series of bombings in the Kharkiv region targeting military and civilian targets. Tuesday’s threat referenced a law the Ukrainian parliament passed April 9 banning Communist and Nazi symbols. The law calls for a nationwide purge of Communist symbols, including statues of Soviet luminaries such as Vladimir Lenin, street names with Soviet references, the display of the hammer and sickle, and the playing of the Soviet national anthem.

Responding to the bill, on April 11, a group of pro-Ukraine demonstrators tore down statues of Soviet leaders in Kharkiv. Ekozyants referenced the teardown in his Tuesday threats.

“Their fate will be the same as the monuments they’ve destroyed,” he said.

The bill’s “decommunization” measures have also sparked backlash from different quarters. Pro-Ukrainian opponents of the move say the measure is too financially costly and risks unnecessarily enflaming separatist violence.

“We have real problems in this country like the war and a bad economy, but we’re stuck talking about ideology,” said Rostislav, a 28-year-old lawyer in Kharkiv. He is pro-Ukrainian and asked to not have his last name used due to security concerns.

“We need money for things other than renaming cities and changing street signs,” he said.

Russia’s top diplomat also criticized the law, claiming it could derail the fragile truce in eastern Ukraine.

“We constantly draw the attention of our partners to it. I think they realize how disastrous such activity of the Verkhovna Rada is for the peace process,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said about the law Wednesday, according to UNIAN.

While Nazi symbols are also banned under the law, Lavrov pointed to ban of Soviet symbols as evidence of a pro-Nazi movement in Ukraine.

“I think they all understand that the continuation of the line on the glorification of the Nazis and de-glorification of real heroes of the Second World War and the Great Patriotic War has risks to undermine the Minsk process,” he said.

Advocates of the law acknowledge the financial cost of decommunization, but say the prolific reminders of the U.S.S.R. degrade Ukrainians’ sense of independence, ultimately leaving the country vulnerable to Russian propaganda.

“We are at war,” Ostap Kryvdyk, an adviser to the vice speaker of Ukraine’s parliament and an advocate of the law, said in an interview. “The attack of Russia on Ukraine is not only a military attack, it is first and foremost an information attack that was started by the Soviet Union before and continued by Russia as the heir to the Soviet empire.”

“Establishing historical justice and paying tribute to the millions killed by hunger and executed in gulags is not a trivial thing,” said Andriy Kohut, a member of the Center for Research on the Liberation Movement, in an interview with Euromaidan Press. “One cannot place bad roads, the currency rate and rising prices, and symbols, dignity, and a pursuit of justice on the same scale of an ideological discussion.”

Responding to questions about the law’s timing amid a fragile cease-fire and weak economy, Kryvdyk said failed attempts to purge Ukraine of its Soviet past dating back to 1991 are to blame for the current conflict.

“This is the time for change, since it is wartime,” he said. “The destruction of the symbols is definitely traumatic. But if we don’t try to resolve these issues today, they will bite later.”

Kryvdyk also pushed back against worries that the move would enflame separatist violence.

“Those people are psychopaths who were looking for an excuse for their crimes,” Kryvdyk said, referring to the Kharkiv Partisans threat. “They already wanted to kill Ukrainians.”

Soviet-era symbols have played a key role in the current Ukraine conflict, often serving as a dividing line between pro-Ukraine and pro-Russia factions.

The black and yellow St. George’s Ribbon, which is a symbol for Soviet victory over Nazi Germany and was awarded as a military and civilian honor in the U.S.S.R., became a symbol for pro-Russia separatists in the current Ukraine conflict and is now banned in cities like Kharkiv.

Soviet symbols are still prolific throughout Ukraine more than two decades after the fall of the U.S.S.R. The red star and the hammer and sickle still adorn many government buildings. Nearly every settlement in Ukraine has a monument dedicated to Soviet war dead in World War II, and major cities on the fringes of the conflict areas like Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Mariupol still have streets named after Vladimir Lenin, which, according to the new law, will have to be renamed.

Even the name of Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine’s fourth largest city with about 1 million residents, will have to be changed. In 1926 the city was named after Grigory Petrovsky, a Soviet bureaucrat who helped draft the Treaty of the Creation of the U.S.S.R. and was an organizer of the Ukrainian famine of 1932 to 1933.

Notably, the bill also renamed the “Great Patriotic War” as the “Second World War,” abandoning a Soviet-era name for the war, which is still used in Russia, weeks before Moscow hosts world leaders on May 9 for the 70th anniversary of victory over Nazi Germany.

Some opponents claim the law is unfair to Ukraine’s Red Army veterans who fought under the hammer and sickle in conflicts from World War II to Afghanistan.

“We had Stalin, OK, that’s our history,” said Rostislav, whose grandfather died in World War II while serving in the Red Army. “But why should we rewrite our history and tell our children something different? We should just remember the people who died.”

Kryvdyk acknowledged the law would be “traumatic” for Ukraine’s Red Army veterans, but said it was a strategic step to change Ukraine’s political culture.

“We will not change the consciousness of those who are 60 or even 40 years old,” Kryvdyk said. “But we have a chance to change the symbolic future of those who are younger.”