After Obama Bows to Pressure, Congress Poised to Have Voice on Iran Nuclear Deal

Josh Siegel /

A bipartisan, unanimous vote by a Senate panel granting Congress the right to review a nuclear deal with Iran has forced President Obama to cede some authority to lawmakers over the negotiations.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee voted 19-0 Tuesday for once-controversial legislation that would allow Congress to prevent the removal of legislative sanctions against Iran.

Obama had originally threatened to veto a previous version of the bill, arguing that congressional action would impede ongoing negotiations with Iran over constraining its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.

But after Foreign Relations Committee leaders were able to compromise on certain aspects of the legislation and it became clear there would be enough votes for a veto-proof majority, the president relented and indicated he would sign it.

The bill will now quickly go before the full Senate and would likely be approved by the House.

“We are the ones who imposed the sanctions; the sanctions regime is what brought them [Iran] to the table,” said Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland, the committee’s ranking Democrat who negotiated the deal with Republican Chairman Bob Corker of Tennessee.

“Only Congress can permanently change or modify the sanctions regime. This provides a way for Congress, in a thoughtful and meaningful way, to review the deal.”

Though Obama was not “particularly thrilled” with the bill, White House spokesman Josh Earnest said “enough changes have been made that the president would be willing to sign it.”

The compromise would shorten a congressional review period for a final Iran nuclear deal and removes language requiring the president to certify that Iran has not supported or carried out an act of terrorism against Americans.

The bill would make Obama submit the final agreement to Congress as soon as it’s completed.

It would reduce the timeframe the Senate has to consider the lifting of sanctions—from 60 days to 52 at most.

During that review period, the president could not waive sanctions levied by Congress, but he could lift sanctions imposed through presidential action. Under the compromise deal, Obama would be required to certify to Congress every 90 days that Iran is complying with terms of the nuclear agreement.

Some lawmakers who accepted the compromise deal did so reluctantly, believing that it does not give Congress enough power.

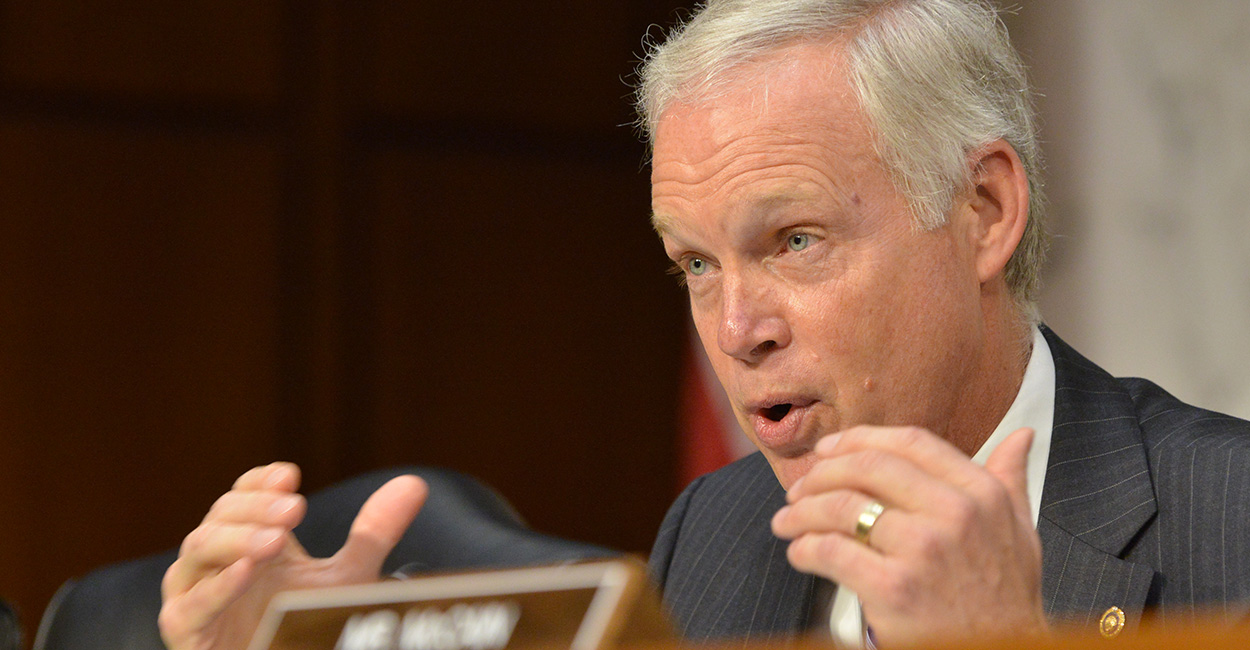

Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., had considered offering an amendment that would have treated the Iran deal like a treaty—prohibiting implementation of the agreement until two-thirds of the Senate, or 67 senators, vote to approve it. Under a treaty, the president could not override that vote with a veto.

“I am not happy with the role [of Congress],” says @SenRonJohnson. “But it is better than no role.”

But under the compromise legislation, Congress could only offer a resolution disapproving the deal, requiring the support of at least 60 senators. And if Obama vetoed the resolution, which he could, two-thirds of the Senate, or 67 votes, would be needed to overturn it.

In an interview with The Daily Signal, Johnson intimated that he withheld his treaty amendment, which Democrats opposed, so that the Senate “could actually pass something.”

“I fully understand and appreciate Sen. Corker getting some bipartisan support so we could actually pass something,” Johnson said. “But it’s disappointing to me that Democrats didn’t believe the American people ought to have more robust input in the process by demanding it be a treaty.”

Johnson said he hopes to clarify to the American people what the review bill “is and isn’t.”

“I have heard reports that this gives us veto power,” Johnson said. “It does not. It’s a relatively minor role [that Congress will have]. It’s a role. I am not happy with the role. But it is better than no role.”

The United States and its five international negotiation partners have said they plan to turn a nuclear framework—announced this month—into a final deal by June 30.

The framework is considered fluid in that U.S. and Iranian leaders have described the details of their interim agreement in different terms.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has already come out and challenged two U.S. priorities of the nuclear negotiations, declaring that all economic sanctions would have to be lifted on the day a final agreement was signed and that military sites would be blocked off to foreign inspectors.

Rep. Lee Zeldin, R-N.Y., told The Daily Signal the Obama administration should expect firm pushback from Congress if a final deal does not contain more certainties.

“It is important for Congress to know exactly what it is agreeing to,” said Zeldin, who would not say if he would support the Corker-Cardin compromise bill.

“At the end of this process, I want to know that Iran has agreed to every word in that deal. Because if anything is left open for interpretation or translation, then there is no deal regardless if it is a good deal or a bad deal.”