How a Bystander’s Video of the Deadly South Carolina Police Shooting Reignited Debate Over Body Cameras

Josh Siegel /

The stark visual of watching a white policeman fire eight shots at the back of a fleeing black man in North Charleston, S.C. this weekend would not have been known to America if not for a bystander capturing the scene on video.

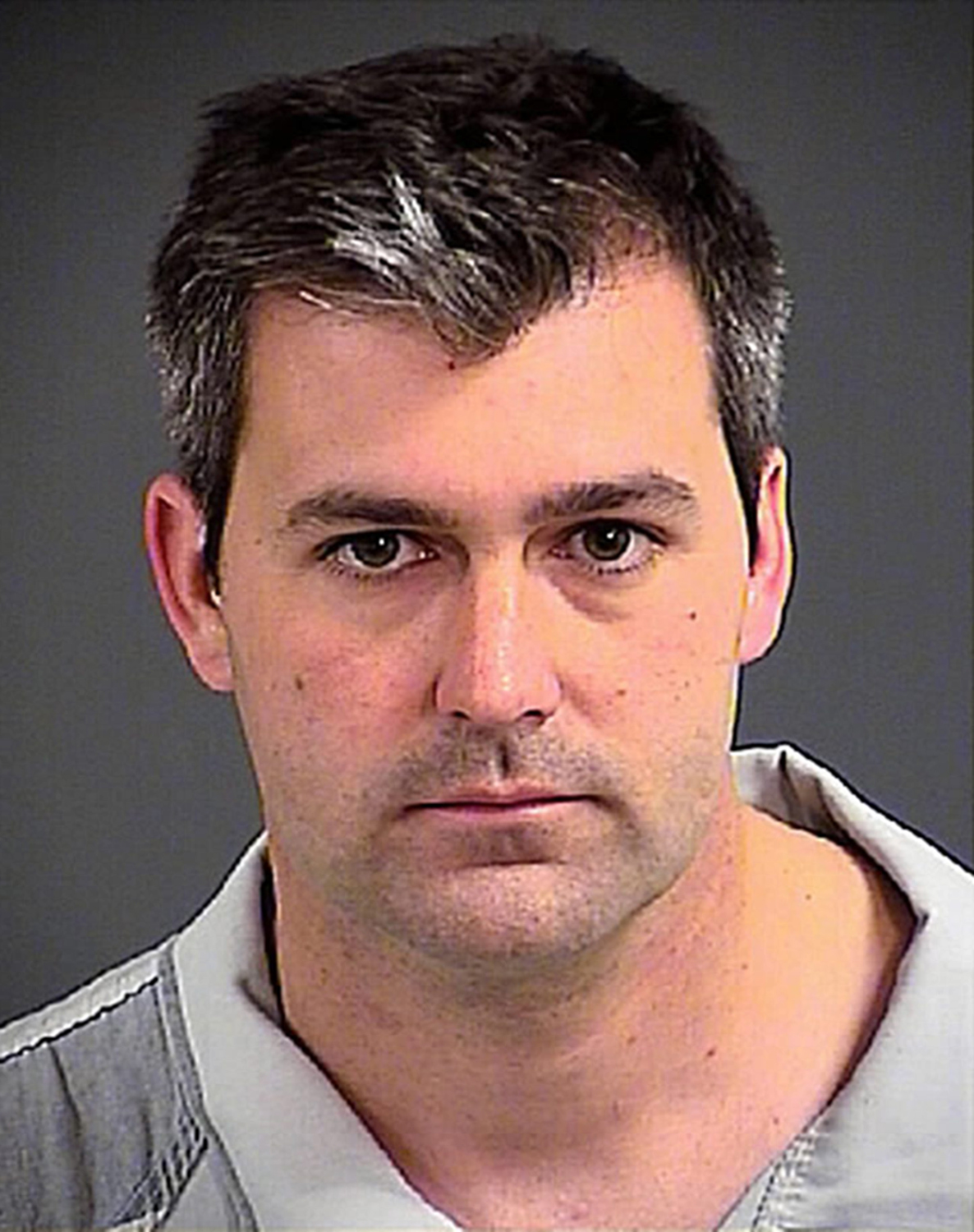

Those precise details as shown in the video allowed the state to charge the officer, Michael T. Slager, 33, with the murder of Walter L. Scott, 50, and reignited a national discussion on police reform.

More specifically, in interviews with The Daily Signal, local officials say they hope the incident will rally efforts to pass legislation that requires South Carolina police officers to wear body cameras.

“There’s a little glimmer of hope,” said Rev. Joseph Darby, the vice president of the Charleston NAACP. “It’s creating a greater call for there to be body cameras, because video does not lie. This went from being a struggle over a taser, according to the officer, to what looked very much like target practice.”

Slager, the officer, reported he feared for life and shot in self-defense after Scott, who was unarmed, grabbed the officer’s stun gun.

Slager had pulled over Scott on Saturday for driving with a broken tail light.

Michael T. Slager, 33, was charged with the murder of Walter L. Scott, 50. (Photo: North Charleston Sheriff’s Office/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

But the officer’s story seemed to be contradicted when a video taken by a man who witnessed the altercation and shooting was made public Tuesday. The officer was then charged with murder. NBC identified the witness to the incident as a man named Feidin Santana.

North Charleston Mayor Keith Summey announced that the officer was immediately fired.

“There’s a little glimmer of hope” in the push for body cameras, says @josephdarby.

Summey said he is ordering body cameras that will be worn by every officer on the city’s police force.

Democratic State Representative Wendell Gilliard, who has sponsored two bills related to body cameras in South Carolina, called Summey’s quick action “a step in the right direction.”

North Charleston Mayor Keith Summey speaks to members of the media and citizens at City Hall. (Photo: Stephen B. Morton/EPA/Newscom)

Gilliard’s body camera bills had been stuck in committee before Scott’s shooting. But now, he says, South Carolina House Speaker Jay Lucas, a Republican, has assured Gilliard he will consider holding a vote on at least one of those bills in the next few weeks.

The first bill would commission a study into the cost and viability of placing body cameras on all South Carolina state troopers. The second one would make all police officers in the state wear body cameras.

“We need to really think for a moment: what if that person [the witness] did not have the audacity to film that most unfortunate incident?” Gilliard told The Daily Signal. “The state would still be on hold, Charleston would be speculating, rumors would be flying, hatred would be flowing. But because that one person took the time and brought the world into this scene that nobody wanted to see, that some don’t want to admit exists, we know that, guess what, it happened. In other words, cameras don’t lie.”

‘Would Have Been Extremely Useful’

Though some officials believe body cameras won’t prevent incidents like Scott’s shooting, some police departments have experienced success in using them, including in Rialto, Calif., which found a reduction in officer complaints and use of force incidents when using cameras.

“Body cameras would have been extremely useful in the Ferguson case and can be very, very good at catching police brutality and at the same time catching false accusations of police brutality,” said John Malcolm, the director of The Heritage Foundation’s Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

Body cameras can be “very, very good” at catching police brutality, says @malcolm_john.

“If I thought it was going to get in the way of a law enforcement action, I might feel differently, but I don’t see that.”

The call for body cameras began last year after grand juries declined to indict police in the killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y.

In the Ferguson case, the Justice Department found a pattern of Civil Rights violations by the city police department and municipal court.

‘The Fabric of the Community’

Darby and Gilliard say North Charleston has long had a troubled relationship between police and black residents.

North Charleston is South Carolina’s third-largest city.

African-Americans make up about 47 percent of residents, and whites account for about 37 percent.

Justice Department data shows the police department is about 80 percent white.

People gather at a memorial on the site where Walter L. Scott, 50, was shot by a white police officer in North Charleston, S.C. (Photo: Stephen B. Morton/EPA/Newscom)

On Wednesday, dozens of people protested outside City Hall in North Charleston. Darby says the protests surprised him because city residents usually keep quiet about what he claims has been a persistent abuse of power by police.

“Charleston has a tradition of not being protest intensive,” Darby said. “If you’ve got 50 folks out there to protest a police shooting, you’ve got a good crowd. It’s something in the fabric of the community where a lot of people have been willing to accept things as they are and don’t want to inflame the powers that be. It’s a fear for what might happen in retaliation.”

But Darby says, “It’s not just a matter of white cops killing black folks or profiling black folks.”

“It goes beyond the race of the police officer,” Darby said. “It’s, ‘I can stop you because I have the right to stop you.’”

‘America’s Problem’

To prevent police abuse, momentum may be on the side of body cameras, says Malcolm, the Heritage law expert.

The body camera issue will probably be handled at the state and municipality level, Malcolm says.

In September, in the wake of the Eric Garner’s death, the New York Police Department, the nation’s largest, began a pilot program equipping a small number of its officers with wearable video cameras.

If Congress or the Justice Department were to try to tackle the issue, Malcolm says they could theoretically hold up federal funding unless a police department adopts body cameras.

For now, Gilliard is focused on his state. He’s calling on South Carolina’s Republican Gov. Nikki Haley to back his body camera legislation.

He wants to avoid tragic incidents like Scott’s, for the sake of the nation.

“This is not just a local problem,” Gilliard said. “It’s not just a problem where an officer got up and had a bad day. This is America’s problem. We need action. You know what will happen. We will have the rallies. We will get the world’s attention. We will say kumbaya and everybody is going to have a good speech. And then we fall back into silence and then, one day, because we choose not to do anything, guess what, it’s going to happen again. It might not be your state today, but it will be your state tomorrow.”