Why Higher Tax Rates Don’t Necessarily Mean More Revenue

David Allen /

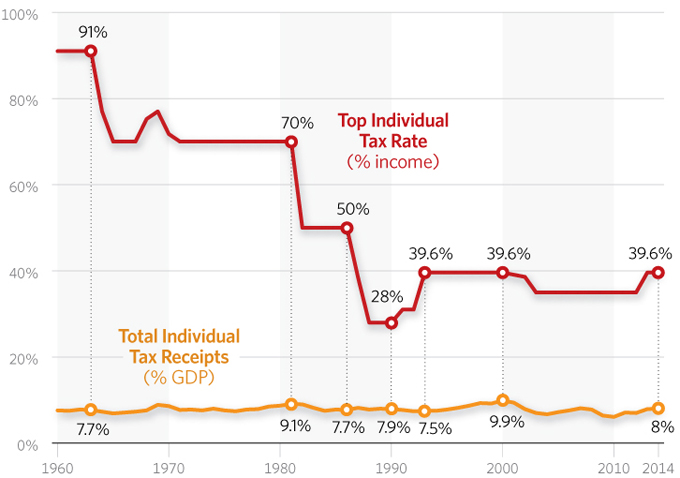

TOP TAX RATES AND TOTAL RECEIPTS

One of President Obama’s major agenda items when he came into office was raising tax rates on the wealthy.

He succeeded: Through Obamacare and the 2013 fiscal cliff tax hikes, he raised rates on their wages, capital gain, and dividend income.

And while it’s true that revenues are likely higher today than they would’ve been had those hikes not occurred, the long-term picture isn’t as rosy. Historical evidence shows it’s probable that revenues will return to around the same level they were before the tax hike.

Consider the chart above, recently released by The Heritage Foundation in its annual Federal Budget and Pictures publication.

It compares changes in the top individual tax rate to changes in total individual tax revenue over the past 50 years. Despite wide variations in the top individual rate—fluctuating between 91 percent and 28 percent tax rates for the richest Americans—total individual revenue has remained fairly stable as a percentage of GDP.

The data suggests that lowering marginal tax rates will not substantially reduce federal revenues, nor do higher rates increase collections.

How can we explain this? The answer comes from the economic effects of tax hikes. Higher marginal rates discourage work, output and employment, leading to lower incomes for individuals. Thus, while increasing rates may bring a higher proportion of incomes into the federal treasury, it also reduces the overall income base these rates are able to draw from.

In other words, when tax rates are higher, people change their behavior. The rich who are paying higher rates under Obama will likely work less because they get to keep less of what they earn. They are likely to delay taking capital gains and dividends. They will also shift their incomes to less-taxed forms, like health insurance and other fringe benefits. All of these changes will reduce the revenue increase from Obama’s tax hikes.

It works the opposite way as well. Our current tax system imposes high marginal rates on individuals and businesses, is biased against savings and investment, and distorts economic decision-making through a complex system of credits, deductions and loopholes. Each of these problems discourages work, investment and risk-taking, which are the building blocks of economic growth.

If Congress overhauled the tax code for the first time in 29 years, it could reduce those high rates that are causing such punitive economic effects. Proposals vary, but the core components of tax reform remain the same: reduced marginal rates and a broadened base.

If Congress did this, economic growth would surge and the government could collect the same amount of revenue it does now with much lower tax rates.