How Arab Spring Opened the Door to Terrorism’s Ugly March

Sharyl Attkisson /

It’s not your imagination. Global terrorism, dominated by Muslim extremist groups, is by far the worst it’s been in modern times.

In the past six years, the United States has added 21 names to its list of foreign terrorist organizations: all but one of them radical Muslim groups. That’s more than the previous 10 years combined.

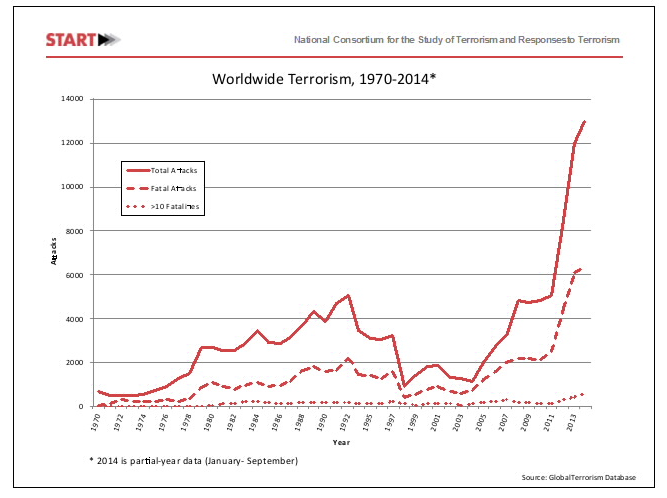

At the same time, the number of terrorist acts has shattered previous records. Experts predict data for 2014, which is still being compiled, will likely reflect more than 15,000 terrorist attacks: a vast increase over 2013—which was already the deadliest year for global terrorism since data was first collected in 1970.

The Institute for Economics and Peace reported 10,000 terrorist incidents killed 18,000 people in 2013. Nine countries were added to the list of nations where more than 50 lives were lost to terrorist attacks in a single year.

Hundreds of people in the Turkish village of Suruc, near the border town of Kobane in northern Syria, accompany the coffins of three Kurdish fighters who died while battling ISIS militants. (Photo: Barbaros Kayan/Newscom)

Arab Spring Devolves Into Terrorist Winter

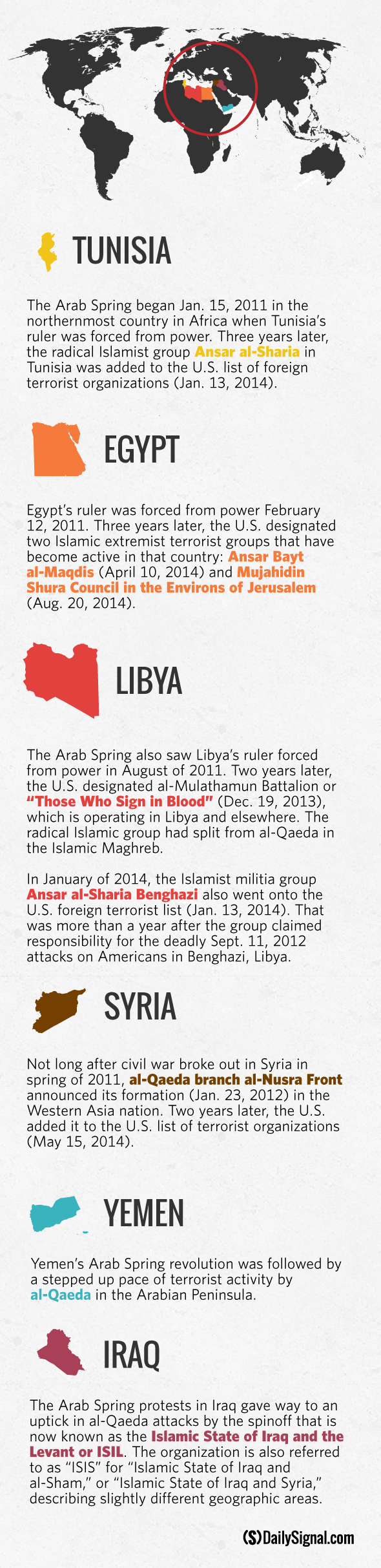

Eleven terrorist groups have been added to the U.S. list of foreign terrorist organizations since the Arab Spring.

“Arab Spring” is the popular name given to the democratic wave of civil unrest in the Arab world that began in December 2010 and lasted through mid-2012.

It turns out the revolutionary movement created an ideal environment for terrorism to grow and thrive.

“Terrorists realized they could exploit the confusion and vacuum in power created by the uprisings,” says a U.S. intelligence officer stationed in Libya during the Arab Spring movement. He says terrorists used social media to stoke civil unrest and take advantage of the chaos.

In the Arab Spring’s wake, Egypt and Tunisia disbanded the security structures that had helped keep jihadists in check, and freed many Islamist and jihadist political prisoners. In Libya, parts of the country fell entirely outside government control, providing openings for violent terrorist movements.

“Many of the regimes weakened or deposed by the Arab Spring were among Washington’s most effective counterterrorism partners,” noted Juan Zarate in an analysis written in June 2011.

A senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Zarate said the political upheaval created “new space” for al-Qaeda and associated terrorist movements to operate where none existed before.

Predictions Fulfilled

The idea that revolutionary uprisings might open the door to terrorists was well-recognized by analysts such as Zarate at the time.

“The chaos and disappointment that follow revolutions will inevitably provide many opportunities for al-Qaeda to spread its influence,” Zarate predicted in an April 17, 2011, analysis. “Al-Qaeda’s leaders … know that this is a strategic moment. They are banking on the disillusionment that inevitably follows revolutions to reassert their prominence in the region.”

Two years later, on Aug. 5, 2013, Zarate warned, “we are now at risk of failing to imagine how the terrorist threat may be changing—well beyond the exclusive al-Qaeda prism.”

Al-Qaeda-Linked Groups: “The Most Lethal”

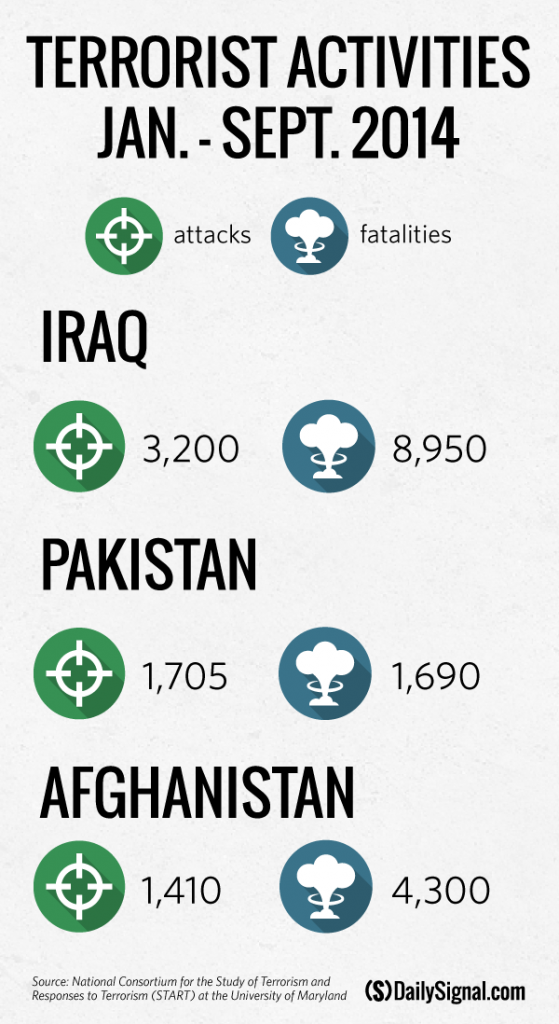

In the first nine months of 2014, nearly 13,000 terrorist attacks killed more than 31,000 people, according to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) at the University of Maryland.

Far from fading away, al-Qaeda’s legacy has only grown, says START Executive Director William Braniff.

“It is clear that groups generally associated with al-Qaeda remain the most lethal groups in the world, and it is their violence that has driven global increases in activity and lethality,” Braniff reported in congressional testimony Feb. 13.

About half of the terrorist attacks and fatalities occurred in just three countries: Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda spinoff ISIS was responsible for more terrorist activity than any other single group.

Today’s Landscape

ISIS has declared itself a “Caliphate,” which refers to an Islamic form of government led by an authoritative power considered a successor to the Muslim prophet Muhammad. Braniff says ISIS sees the growth of its Caliphate as “the means to the end of a final, decisive military confrontation with the West.”

“In countries where terrorism crowds out nonviolent activism, civilians often have little choice but to align with extremist organizations out of concerns for self-preservation,” Braniff says. “This is one mechanism in which extremist ideologies and groups can gain sway over larger swathes of society.”

Zarate, author of “Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare,” says ISIS is “piggy-backing” off the work of al-Qaeda and beginning to advance the global agenda of Sharia rule.

Sharia calls for harsh punishments, such as stoning, amputation or execution, for offenses such as wine drinking and infidelity.

Most Muslim countries do not strictly employ these classic punishments, but the United Nations estimates thousands of women are killed each year in Sharia-justified “honor killings”: victims murdered for bringing “dishonor” to one’s family. ISIS has become known for employing other Sharia measures such as genital cutting, child marriage, stoning and execution by crucifixion.

ISIS fighters holding the Al-Qaeda flag with “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant” written on it. (Photo: Medyan Dairieh/Newscom)

“I worry about what the strategic implications are if groups like ISIS have physical space, leadership and innovation to bring their wild imaginings to fruition,” says Zarate, a former deputy national security adviser for combating terrorism.

“Anytime we allow terrorist organizations with smart, committed and dedicated groups of individuals to adapt and think strategically about how to pursue their agenda to include attacking the U.S.—that’s a dangerous position to be in.”