US-Funded News Station Wants to Bring Free Press to Cuba. But Raúl Castro Wants to Shut It Down.

Josh Siegel /

MIAMI—Carlos García-Pérez, who heads the U.S. government’s Office of Cuba Broadcasting, is used to his news station being a target.

The Miami headquarters of Radio and TV Martí is protected as if it is one. Located randomly off the side of an expressway, the building is guarded by a barbed-wire gate.

Signage outside confirms the news station as U.S. government property, and visitors are asked by a uniformed guard to not bring their cell phones into the building.

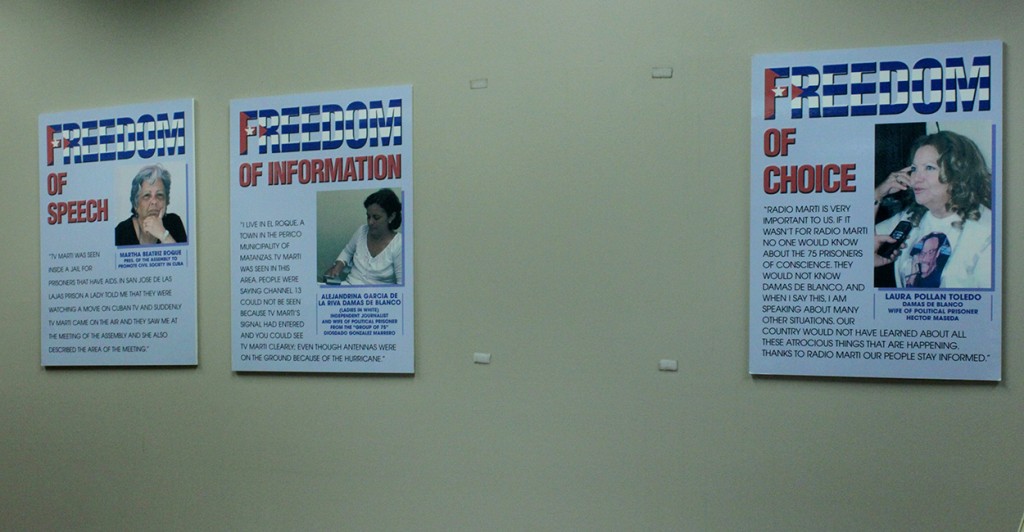

The federal government launched Radio Martí in 1983 and TV Martí in 1990 with the hope to combat communism by exposing Cubans to freedom and democracy, providing uncensored information from Miami to Cuba.

Since the beginning, the Castro regime, notorious suppressors of free press, has worked hard to block the station’s programs.

Today, the Cuban government sometimes successfully jams its transmissions, especially in Havana, the capital.

But last month, Raúl Castro, Cuba’s president, took the shutdown efforts to a new level.

Speaking at the Summit of the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States in Costa Rica, Castro laid out conditions for normalizing relations with the United States.

One concession he hoped to extract was predictable—and rejected outright by the Americans: returning the U.S. naval station at Guantanamo Bay to Havana.

Castro’s second demand was more discreet, seemingly small, but his target obvious: He wants the end of Radio and TV Martí.

Castro did not directly name the Martís, instead, criticizing “radio and television broadcasts which violate international norms.”

García-Pérez got the message loud and clear.

“It’s a badge of honor that the Cuban leadership goes to San Jose, Costa Rica, in front of all the Latin American leaders, and says one of things that I want is to stop the transmissions from Radio and TV Martí,” says García-Pérez in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“The fact he is going out and saying that speaks of our impact on the island.”

“It’s a badge of honor” that Cuban leadership wants to shut the Martís

down, says Carlos García-Pérez.

The U.S. State Department’s top negotiator with Cuba, Roberta S. Jacobson, last week testified to the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the Americans “have no plans” to end the Martí’s broadcasts. That may be true, but President Obama has other plans for the station.

In his 2016 budget, Obama proposes to de-federalize the Office of Cuba Broadcasting, establishing an independent grantee, as a private nonprofit, to incorporate the Martís. Congress would ultimately have to approve the plan.

The federal government launched Radio Martí in 1983 and TV Martí in 1990 after its namesake, Jose Martí. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

Since Obama took office, the Office of Cuba Broadcasting budget has steadily declined.

After receiving a peak of $36.9 million in 2006 when George W. Bush was president, Congress gave it $29.2 million in 2011. Last year, it was budgeted about $23 million.

The cautious retreat from the Martís has been backed by efforts in Congress to turn off the station’s programming. In January, Rep. Betty McCollum, D-Minn., introduced the Stop Wasting Taxpayer Money on Cuba Broadcasting Act, aimed at shutting down Radio and TV Martí.

For years, some in Congress have openly criticized the operation, accusing it of cronyism, patronage and bias.

But under García-Pérez, who became director in 2010, the Martís’ content has become less anti-Castro and more straight news, including reports produced on the island by Cubans.

Under Carlos García-Pérez, who became director in 2010, the Martís’ content has become less anti-Castro and more straight news. (Photo: Jamie Jackson)

It has also shed waste, grounding “Aero Martí,” an unsuccessful effort to use an aircraft to send TV Martí signal into Cuba from United States.

When The Daily Signal visited the Office of Cuba Broadcasting last week, García-Pérez was relentlessly charming, eager to show off Martís’ newfangled multimedia ambition.

Sitting in a room with a view of the newsroom—where journalists from the Martí’s TV, radio and Internet properties work amongst each other—García-Pérez dances around questions about whether he’s bothered by the dissent, and specter of shutdown, surrounding him.

In fact, García-Pérez, insists the Martí’s role will become more important as the United States and Cuba restore diplomatic relations.

On the day Obama announced his new engagement with Cuba, more than 27,000 users visited Martínoticias.com, the news station’s online platform, though the TV station did experience technical problems, struggling with a live shot and translation issues.

“We don’t try to anticipate the future,” García-Pérez says. “We try to participate in the future. We provide news and information that is relevant to the daily lives of the Cubans, so they can have information on what’s going on inside the island, Latin America and the rest of the world. That way, they can make educated decisions about their future. Our job today and our mission is more important than ever. No question.”

Elusive Target

As the targets against it have become sharper, the Martís have found ways to penetrate Cuba under García-Pérez, a U.S.-born Cuban-American trial lawyer who grew up in Puerto Rico.

A new multimedia focus serves as both a way to keep up with a changing journalism landscape and to keep away the Cuban government.

The Martís programs are carried 24/7 on Hispasat satellite TV and on DirecTV, which broadcast in most of Latin America.

It distributes DVDs—about 15,000 per month—and flash drives containing its programs throughout Cuba, which are copied and delivered by activists, journalists, bloggers and opposition members. It shares content with Mira TV, a South Florida news and entertainment outlet.

In May, the Martís introduced Reporta Cuba—a social media platform that collects information and news tips through citizen reporters across the island.

“We like to see ourselves as a two-way communication station,” García-Pérez says.

“We just don’t send information to the people of Cuba. We also get their input, comments and perspective on several news events that are happening on the island. This is what we became. We became a multimedia operation. Just like anyone else in the business. It used to be radio, TV and the website. Now, we integrated our resources. We share resources, we share information amongst all platforms, and we are so much more efficient than what we used to be.”

García-Pérez admits that it’s “impossible” to measure if the Martís’ efforts to actually reach the Cuban people are working.

According to the Government Accountability Office, a 2008 telephone survey found that viewership of TV Martí was less than 1 percent of the Cuban population. The U.S. government ended the surveys after that, claiming that obtaining accurate data is too difficult.

It’s difficult to measure viewership of TV Martí broadcasts, but the station hopes embracing multimedia will help reach more people. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

A 2010 report by the majority staff of Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by now-Secretary of State John Kerry, alleged that Martí’s broadcasts have failed to make “any discernible inroads into Cuban society or to influence the Cuban government.”

García-Pérez contends that the Cuban government wouldn’t be so intent on stopping the Martís if the station were not making an impact.

“It’s impossible to measure,” García-Pérez says. “You can’t walk around with a clipboard and ask how many people are listening to Radio and TV Martí. But free press is non-existent in Cuba. That’s why we exist. We know they are watching and listening. Absolutely.”

A Connected Newsroom, Tied by Cuba

You know it’s an important day at TV and Radio Martí because the station has interrupted all of its daily programming, on every platform, to broadcast hours of congressional hearings on the new U.S.-Cuba policy.

“We are the only news source bringing this content to the island,” says Natalia Crujeiras, the Martí’s chief content officer, a new position that oversees editorial material on all platforms.

The Martís use pool video and sound from Voice of America, a sister organization, but Crujeiras has also dispatched her own reporter to Washington for the three days of hearings.

Last week, the Martís dedicated all of its platforms to cover hearings in Congress on the new U.S. policy with Cuba. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

On this day, a TV Martí journalist reports on the Central American and Caribbean Games from Puerto Rico. It is the first time Cuban baseball players are competing in the U.S. territory, and the Martí reporter shoots and reports video packages for television, but also writes for the website and calls into radio programs with updates.

“It’s so we can amplify the use of one resource,” says Crujeiras. “Having an open newsroom allows us to cross-promote our content and to help each other cover stories.”

Besides having a full-time staff in Miami, the Martís employ contractors in Cuba, Venezuela and even Europe. They are looking to hire a Washington, D.C., reporter.

At Radio and TV Martí, reporters and anchors are expected to be able to report for multiple platforms. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

Crujeiras, a trilingual veteran reporter born in Mexico who has worked for Telemundo and Univision, has the global perspective to run a open newsroom, where reporters of different skills and beliefs work together.

Like most of the reporters, Crujeiras shares a connection to Cuba.

Her grandfather’s best friend—who she considered family—was a Cuban exile, and Crujeiras married a Cuban-American in Miami.

“I became Cuban in a way,” says Crujeiras, whose office is decorated with a painting of Jose Martí, a freedom-promoting Cuban hero and nationalist and the namesake of TV and Radio Martí. “My heart is Cuban. My kids are part Cuban and Mexican. In our house, it is an example of the American melting pot.”

Crujeiras, who’s worked at the Martís for two-and-a-half years, is sensitive to questions about the station’s journalistic integrity.

Memories of Jose Martí, a freedom-promoting Cuban hero and nationalist, consume Radio and TV Martí. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

The 2010 Senate Foreign Relations report cited “problems with adherence to traditional journalistic standards,” and even recommended that the Martís incorporate with Voice of America and move it its headquarters to Washington, to ensure better oversight.

García-Pérez and Crujeiras would not speak directly to such complaints that came before their time, but they vow to stay right where they are, in Miami, to be closer to Cuba.

Though Obama’s decision to engage the Cuban government sparked intense personal convictions from Martís’ journalists, as it naturally would for people so connected to the island, Crujeiras describes an uncheckered commitment to truth.

“Listen, I grew up in a country where although there’s separation of powers, pretty much the government would filter and censor the major newspapers,” Crujeiras says.

“Here, I am in a country where my check is paid for by the American government, but I am allowed to report the story the way I think it should be as a journalist. Because I am a professional journalist with 15 years of experience. I am not a spokesperson for the government. I cover news stories, sometimes critical of the administration. I think that’s a gift very few countries in the world have.”

‘Defend Those Who Don’t Have a Voice’

Recent Cuban refugee Luis Felipe Rojas, a reporter at the Martís, appreciates the chance to report the news freely.

Rojas, a short, serious man with a weary face and a hoop earring, built a news blog with a 250,000-person following inside Cuba.

“The government tried very hard to stop it,” Rojas says, as Crujeiras translates his Spanish to English.

The Cuban government “tried very hard to stop” Luis Felipe Rojas from reporting the news.

In the last two years before he came to the United States, Rojas says he was subjected to more than 20 arbitrary arrests, and physical abuse at the hands of state security—all for doing a job few would dare try.

“[If I wouldn’t do it], otherwise no one could do it,” Rojas says. “I thought I had to choose to do it. I decided to request the refugee benefits after realizing that I was becoming less effective as a blogger and freelance journalist. [On only rare] occasions I was able to take pictures or participate [as a journalist] in events related to civil society or collect data related to human rights violations by the Cuban regime.”

Rojas moved to the United States on Oct. 25, 2012, under a refugee program that the American government offers Cubans who are persecuted for their opinion, peaceful rebellious actions or their religious preferences.

Cuban refugees who report for Radio and TV Martí embrace the U.S.’ free media culture. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

Rojas had been working with the Martís since 2006, on a freelance business, but took on a full-time role after moving to Miami.

Today, he hosts a daily conversational radio show called Contacto Cuba (Cuba Contact) and writes for the Martí website.

Now, when he reports on people living in Cuba, he feels like he is telling his own story.

“The big difference now is I hear from our audience and from the people who are the newsmakers in civil society, and I help distribute and amplify that voice,” Rojas says. “That before was my voice. We should always defend those who don’t have a voice.”

‘We’re a Problem’

García-Pérez and Crujeiras maintain that an improved U.S.-Cuba relationship requires the Martís to expose all of the many voices who will be impacted.

The Martí’s leaders describe their coverage of the new policy as “wall-to-wall,” seeking out reaction and analysis from prominent opposition activists, and also, regular people.

“We’ve had people on our shows who are for and against the Dec. 17 announcement and we have people who are in the middle,” García-Pérez says. “We don’t discriminate. We want our audience to have a full picture and a full spectrum of ideas as to what this implies.”

After García-Pérez “recognized the mistake” of its technical problems the day of Obama’s announcement, the Martís used its contractors in Cuba to gather reaction from the Cuban people. Some would text their feelings to Martís reporters and producers in Miami.

“I think there’s a lot of confusion [from the Cuban people on the new relations with the United States],” Crujeiras says. “There’s one group of people we’ve had feedback on that are very positive, enthusiastic and very hopeful: the perception is the American people are coming to save us. There are other areas of civil society feeling well, now what—you have diplomatic relations but what does that mean? I still cannot express myself.”

Despite its uncertain future, García-Pérez says the Martís will be there to “fill in the gaps” for the Cuban people.

Carlos García-Pérez insists he has the support of Congress and the White House. (Photo: Josh Siegel)

García-Pérez insists he has “very strong supporters” in Congress—and the White House—to continue to carry out the Martís’ mission.

He was careful in predicting what it would mean if Congress were to approve Obama’s proposal to move the Martís outside federal control.

“This organization would adhere to the same standards of professional journalism required of the Martís currently,” García-Pérez said. “The commitment to our vital mission to serve the audience in Cuba is undiminished.”

He said he “hopes” a potential shutdown of the Martís to appease Castro “won’t be on the table.”

But García-Pérez and Crujeiras know that is outside their control. Control is a funny thing, after all.

“As long as there’s no free press in Cuba, and they try to control the message, we are a necessity to the Cuban populace,” Crujeiras says. “You are always going to have people that approve what you do, people that criticize what you do. That’s part of the game. But at the end of the day, our job is still to provide the people of Cuba with information they otherwise wouldn’t have. It’s funny, I think of it this way—if the Cuban government is asking for our broadcast to be stopped it’s because we are doing a good job. We’re a problem.”