Why Is the United States’ Economic Freedom Ranking So Low?

Ed Feulner /

If you were to rank all the countries of the world based on their level of economic freedom, you’d think the United States would be a shoo-in for first place, right? Surely we would be at least somewhere in the top five.

If you were to rank all the countries of the world based on their level of economic freedom, you’d think the United States would be a shoo-in for first place, right? Surely we would be at least somewhere in the top five.

We’re not. We’re not even in the top 10.

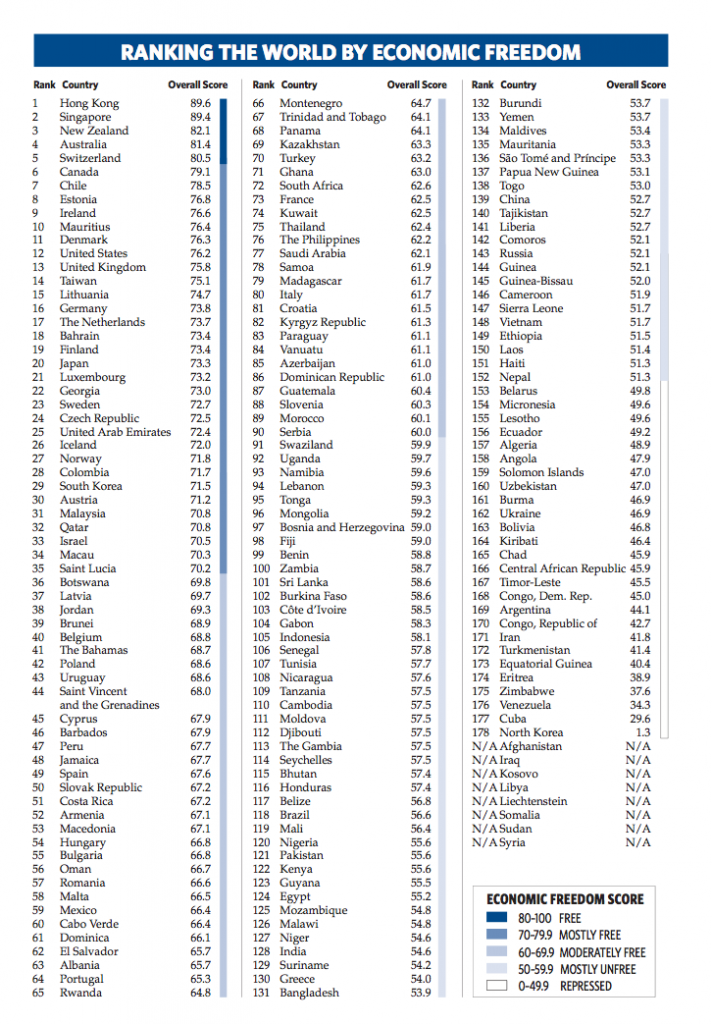

Because this isn’t a hypothetical question. Every year, the Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal release a detailed, country-by-country policy guide known as the Index of Economic Freedom. The news for the United States had been getting a little worse each year over the last several editions.

Notice I said “had.” The steady decline charted by the United States since 2008 was, I’m glad to report, halted this year. The 2015 index shows that our score ticked up a bit. And we were the only economy in North America to improve. The scores for both Canada and Mexico declined in the latest edition.

The United States still stands at No. 12 globally. Not a bad finish on a list of 178 countries, but still we’re trailing Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland, Canada, Chile, Estonia, Ireland, Mauritius and Denmark. The question is, why?

As recently as 2008, the United States ranked seventh worldwide, had a score of 81 (on a 0-100 scale, with 100 being the freest), and was listed as a “free” economy (a score of at least 80). Today, it has a score of 76.2 and is “mostly free,” the index’s second-tier economic freedom category.

Before explaining why, let’s look at how the editors of the index determine the scores. Each country is evaluated in four broad areas of economic freedom:

First, rule of law. Are property rights protected through an effective and honest judicial system? How widespread is corruption — bribery, extortion, graft and the like?

Second, limited government. Are taxes high or low? Is government spending kept under control, or is it growing unchecked?

Third, regulatory efficiency. Are businesses able to operate without burdensome and redundant regulations? Are individuals able to work where and how much they want? Is inflation in check? Are prices stable?

Fourth, open markets: Can goods be traded freely? Are there tariffs, quota or other restrictions? Can individuals invest their money where and how they see fit? Is there an open banking environment that encourages competition?

For the most part, Americans can be proud of how the United States does on these measures. For example, we’re well above the world average on property rights (though they’ve been “uneven,” the index editors note, with courts having to step in when the executive branch has overreached). Our average tariff rate is low (1.5 percent). Our labor market is flexible.

But in many other areas, the United States could be doing a lot better. “The anemic post-recession recovery has been characterized by slow growth, high unemployment, a decrease in the numbers of Americans seeking work, and great uncertainty that has held back investment,” the editors write.

Other weak spots include:

Regulations: Since 2009, more than 150 new major rules have been introduced. The annual cost exceeds $70 billion. And more are on the way.

Health care: Implementation of the so-called Affordable Care Act has reduced competition in most insurance markets, and it remains a drag on job creation and full-time employment.

Size of government: The top individual income tax rate is 39.6 percent (versus 29 percent in Canada). The United States has one of the world’s highest corporate tax rates: 35 percent (more than twice Canada’s 15 percent rate). Government spending tops one-third of our annual gross domestic product (the value of all the goods and services our nation produces).

“Overall, the U.S. economy continues to underperform,” the editors write. Is that our destiny? To underperform? Or can the United States regain its lost ground and prove that it can be a leader in all areas of freedom?

I’m convinced that we can, but only if we’re willing to hold our elected officials accountable and demand change. It’s up to us.

Originally appeared in the Washington Times.