The State of the Union: What It Is and Why It Matters

Philip Wegmann /

This Tuesday, President Obama will face the toughest crowd of his presidency when he delivers his State of the Union address to the newly controlled Republican Congress.

Each president’s State of the Union offers a distinct historical snapshot while continuing an enduring constitutional tradition.

The president is expected to underscore past policy victories, like Obamacare, while outlining future initiatives, including federally subsidized community college and accompanying tax increases.

More than an administrative photo-op, each State of the Union exists as a historical microcosm of a particular moment in the American experience.

During the 1862 State of the Union, as the Civil War tore the nation asunder, President Abraham Lincoln urged Congress to abolish slavery to preserve freedom. When Nazi tyranny threatened European liberty, President Franklin D. Roosevelt used his address to urge a neutral Congress to resupply America’s future allies.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering the State of the Union address on Jan. 4, 1939. (Photo: Everett Collection/Newscom)

Before Congress in his 1965 address, President Lyndon B. Johnson outlined his Great Society, a conglomeration of liberal assistance programs. Then in 1996, President Bill Clinton announced historic welfare reform declaring that “the era of big government is over.”

From George Washington to Barack Obama, each address has punctuated a specific historical American epoch.

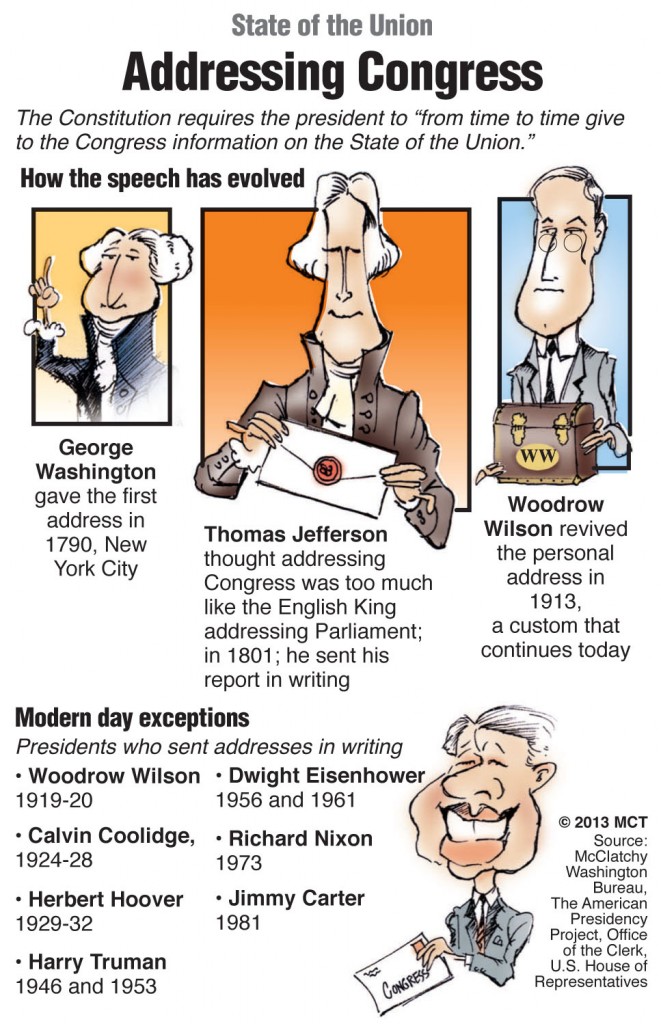

A constitutional cornerstone, the annual State of the Union hallmarks the institution of democratic mixed government. Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution mandates that the president “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union.”

Unlike the British crown in Parliament model, the U.S. executive only addresses Congress at the express consent of a coequal legislature. When invited by the speaker of the House, the president must give an account for the health of the union.

Once a year for this address, the whole government gathers in the House chamber as representatives sit next to senators as well as Supreme Court justices and cabinet secretaries.

In 1790, George Washington first fulfilled this responsibility delivering the address, in person and verbally to Congress, then housed in New York City.

Concerned that an oral address smacked of monarchical ceremony and privilege, President Thomas Jefferson presented Congress with a written address in 1803. Following suit for the next century, each subsequent president submitted written addresses.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson broke the mold.

A vocal progressive and proponent of increased executive authority, Wilson chose to deliver the address directly, a controversial decision. On the eve of his speech, one newspaper headline captured the mood of the nation, “Wilson to Read Message in House: Washington Amazed.”

Since Wilson, presidents have read their State of the Union addresses in person (with a few exceptions). With the advent of mass media, the speech has developed a more democratic flavor as presidents address both Congress and the nation.

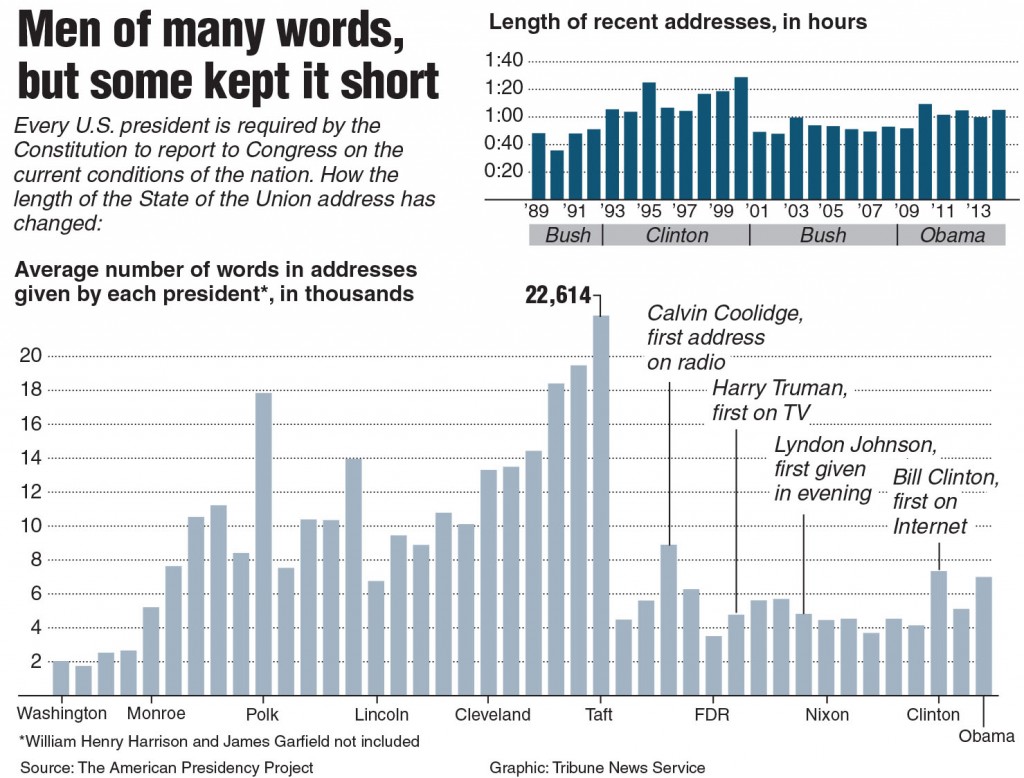

In 1923, President Calvin Coolidge, otherwise known for his silence, was first to give an address broadcasted over radio. President Harry Truman did it on live television in 1947. In 1965, Lyndon Johnson was the first to deliver during primetime.

President George W. Bush was the first to provide a live webcast of his State of the Union in 2002, and the first to give his speech in high-definition television in 2004.

Though required to give a thorough account during the State of the Union, the length of different addresses varies.

The shortest on record, Washington’s 1790 address, was little more than three pages long with 1,089 words. Clinton gave the longest spoken address packed with 9,190 words.

As unique as the administrations that authored them, each State of the Union offers a distinct historical snapshot while continuing an enduring constitutional tradition.