As Obama Vows to Nix Keystone Pipeline, Here’s a History of Presidential Veto Power

Philip Wegmann /

Minutes into the beginning of the 114th Congress last week, before any bill left either chamber, the White House vowed to veto legislation approving construction of the Keystone XL pipeline.

“If this bill passes this Congress, the president wouldn’t sign it,” White House press secretary Josh Earnest told reporters Tuesday.

That showdown could come soon. The House approved the measure Friday, 266-153. It now moves to the Senate, where it is expected to pass with Democratic support.

So far, President Obama has used his veto pen only twice, less than any executive in more than a century. In 2010, he vetoed a controversial bill that allowed for expedited mortgage foreclosures and another continuing resolution rendered moot by other legislation.

With the composition of the new Republican-controlled Congress, though, Obama warned in a December NPR interview, “There are going to be some times where I’ve got to pull that pen out.”

Congress can only overturn a presidential veto with a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate.

The president may have plenty of opportunities given the eagerness of Republicans in Congress.

An enduring hallmark of executive authority, presidential veto power was designed as an integral constitutional safeguard, granting the chief executive “partial agency” over the legislature while preserving the separation of powers.

Though never explicitly mentioned by name, veto power is specifically outlined in Article I, Section 7 of the U.S. Constitution. The president is empowered “to return [a bill], with his objections to that House in which it shall have originated.”

Congress can only overturn a presidential veto with a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate.

Veto power has endured a complicated evolution throughout American history.

George Washington made the first veto to strike down the Congressional Appointment Act of 1792. Washington declared the act an unconstitutional violation of equal representation, thereby underscoring the classical understanding of veto power.

This theory peaked during the presidency of Grover Cleveland, who issued the second most vetoes in history: 414. (During his second non-subsequent term, he issued another 170).

In 1887, Cleveland defended his veto of the Texas Seed bill, a relief measure for Texas farmers, as he could “find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution.”

Conceptions of presidential veto power evolved with an emerging progressive interpretation of the executive and the subsequent presidency of Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson interpreted veto power along with other presidential power as “anything he has the sagacity and force to make it.”

Though Wilson issued just 44 vetoes, this theory of presidential veto power reached its zenith with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Defending much of his New Deal and other policy initiatives, FDR issued 635 vetoes—more than any other president in history.

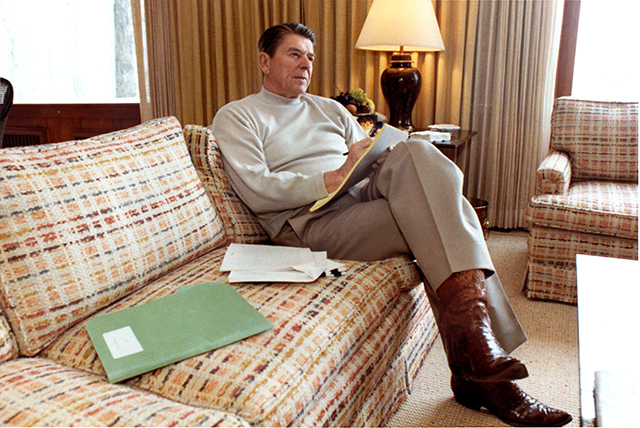

In modern times, besides President Ronald Reagan, who vetoed 78 bills, most other presidents exercised comparative restraint.

During his time in office, President Bill Clinton vetoed 37 measures—including Arctic drilling and a partial-birth abortion ban—and President George W. Bush vetoed just 12 bills.