Elijah’s Story: A Life Saved Before Birth

Josh Siegel /

DE PERE, Wis.—Eight weeks before he was born, Elijah Leffingwell met the outside world.

On Sept. 21, 2012, at 25 weeks, Elijah was partially removed from his mother’s womb so surgeons could surgically remove a tumor the size of an orange from his left lung.

Midway through the surgery, his heart stopped. The doctors massaged it back to life and Elijah went back inside his mom’s womb.

>>> Related: 46 Touching Photos That Prove Love and Science Work Miracles

If not for this rare operation, done before Elijah’s birth to stop the tumor from smothering his heart and right lung, Elijah never would have walked the earth.

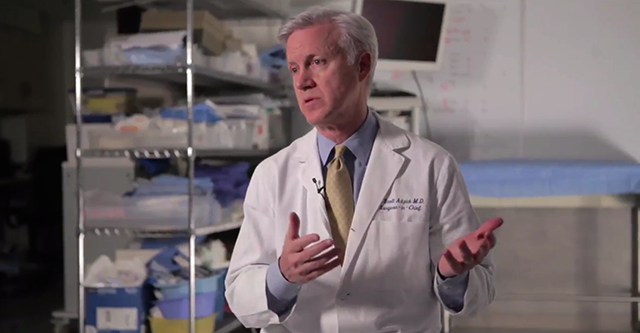

“He would have died,” says Elijah’s primary surgeon, Dr. Scott Adzick of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “No question. He would have died if the operation were not done before birth.”

But today Elijah lives—cautiously—as if at 2 years old, he already understands the fragility of life.

“He walks through life making sure he is going to be OK,” says April Leffingwell, Elijah’s mother, describing her son — a model of a boy with golden hair, pink cheeks and soft features who keeps strong eye contact with people near him, as if he has a lifetime of experiences and can relate to what they’re saying.

Last week, as part of a series on fetal surgery, The Daily Signal visited the Leffingwells’ apartment in this suburb of Green Bay.

The Daily Signal also traveled to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the worldwide leader in fetal surgery known as CHOP, where Elijah had his procedure done and spent his first 66 days after birth.

Although fetal surgery has existed since the 1980s, there have only been about 40 fetal surgeries worldwide for Elijah’s particular condition, a sometimes fatal lung lesion called congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, or CCAM.

In general, because of the danger to both mother and child, doctors reserve fetal surgery for the worst cases of the most severe defects.

At the hospital, Adzick, who helped pioneer fetal surgery, says he has performed nearly 30 of these surgeries for CCAM since the first such operation at the hospital in 1995.

Now an established field, the science of fetal surgery has advanced to where surgeons can treat nonfatal birth defects such as spina bifida.

And in the not-so-distant future, medical professionals expect to be able to use stem cell and gene therapies to treat an even wider range of diseases in utero, with less risk.

“To treat what is expressed as a disease after birth before birth is the ultimate preventive therapy,” says Dr. Scott Adzick, Elijah’s surgeon.

“You can imagine the payoff if that would work,” says Adzick, noting that his colleague, Alan Flake, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has been pursuing the science of using cell therapy in the womb for 30 years. “It would allow us to treat successfully thousands and thousands of patients. To treat what is expressed as a disease after birth before birth is the ultimate preventive therapy.”

For the Leffingwells, the magic of fetal surgery–what once seemed like “science fiction” to them–is an inescapable part of their lives, lived out through Elijah’s successes and struggles, memorialized through keepsake photos and get-well cards and told and re-told through sharing the story in hopes it inspires other families to live without regret.

‘Cautious Little Boy’

The Leffingwells’ temporary home is fitted to satisfy the unique needs of a child whose scarred body has been playing catch-up since even before he was born seven weeks prematurely.

April, who bears scars like her son, a constant reminder of how their lives are joined, describes Elijah’s challenges as she prepares his lunch.

“I don’t know if he really knows hunger,” April says, as she yanks out two Ziploc bags of pre-sliced avocados from a freezer. “He doesn’t have the desire. We have to force him to fatten up.”

For a year now, Elijah has been able to chew and swallow like other children.

But during the first year of his life, he was fed through a feeding tube.

So the lunch, and Elijah’s pickiness toward it — he prefers the low-calorie celery to the protein-packed peanut butter sandwich — counts as a milestone.

“Just take one bite of peanut butter please,” April tells Elijah, in yet another attempt to encourage her son to eat big, as she does when she adds whipping cream to his milk.

Elijah’s 4-year-old big sister, Ellianna — a fiery redhead with piercing blue eyes — is more aggressive with her sandwich, diving into the main portion like most growing children would.

“I am the most amazing,” Ellianna declares unprovoked at one point.

“Ellianna is more like, ‘Bring it on,’” April says of her firstborn. “Whereas, Elijah, since he was born, is a really cautious little boy. I remember coming home the first time and giving him a bath was so difficult, and changing his diaper was so hard. He would cry and scream.

“Everything new was hard for him to adapt to. Even now. Meeting new people. Trying new things. The wind in his face. The snow in his hands. I don’t know if it’s because of everything he’s been through or if it’s just who he is.”

Perfect, and Then Pain

Before April and Elijah together endured a lifetime of obstacles, there was the “perfect” pregnancy.

Ellianna came to the world easy. Midwife, natural, no medicine.

“My first pregnancy was everything I wanted,” April says. “Elijah was everything I wouldn’t wish upon anybody.”

April and her husband, Jason—lifelong Wisconsinites who met over a shared interest in rock bands such as the Grateful Dead and Phish—wanted their children two years apart.

So they tried again.

The second pregnancy was tragic. It was an ectopic pregnancy and the eight-week old fetus died on Christmas.

A few months later, April and Jason conceived Elijah. Because she was at high risk for another troubled pregnancy, April had several ultrasounds: four weeks, eight weeks, 12 weeks.

The 20-week ultrasound, when the baby’s sex is usually revealed, showed the tumor.

One in 10,000 babies have CCAM.

“Not knowing if your child is going to live after just losing a child, we asked, ‘Why us?’, especially after having such a perfect pregnancy with our daughter,” April says. “It just didn’t make sense. It crushed us.”

April’s midwife downplayed the tumor as “probably nothing” and assured that surgery could happen after birth.

Typically, as fetuses with CCAM keep growing, the tumor stops, and it can be removed after birth.

April shares a photo of Elijah’s tumor, which was the size of an orange. (Photo: Courtesy of April Leffingwell)

Fetal surgery is rare. April and Jason wanted to be sure.

After initially resisting doing their own research for fear of the unknown, April and Jason discovered fetal surgery.

The research led them to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Adzick.

From 1983-85, Adzick served as a fellow under Michael Harrison, considered the “father” of fetal surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. Adzick then worked with Harrison as an attending surgeon from 1988-95.

Together, they developed the fetal surgery enterprise—first testing on animals, graduating to clinical trials, and then, the real thing.

“[The] idea arose from the frustration of caring for babies after birth and realizing it’s too late: The damage had already been done,” Adzick says in an interview at the hospital. “We had to get to the baby earlier, while still inside mom.”

Dr. Scott Adzick, chief of surgery at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, helped pioneer fetal surgery in the 1980s.

In 1995, Adzick left San Francisco to launch the fetal surgery program in Philadelphia.

“He is the man,” says Jason, who wore jeans with colorful patterns stitched on the rear during the interview at the Leffingwell’s home. “We picked [CHOP] because of Adzick.”

‘There Wasn’t a Choice’

At the time of the diagnosis, the Leffingwells had just moved into a new home in Mequon, Wis.

When the Leffingwells—with then-2-year-old Ellianna in tow—left for Philadelphia, Elijah’s bedroom didn’t yet have a crib in it.

The family moved to a room at the Ronald McDonald house in Camden, N.J., a city that had the highest crime rate in the United States in 2012.

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, April underwent a full day of testing.

Elijah’s tumor had grown so large he was already suffering heart failure.

“The tumor kept growing,” Adzick says. “So the baby was going to die. In the meantime, babies with heart failure with this circumstance can make the mother sick by making the placenta—the hookup between the mother and baby—full of fluid and put her in toxemia of pregnancy. So it’s not only a risk to the baby who would be doomed to die without fetal surgery, but also a risk for the mother to get sick.”

“The baby was going to die” if not for fetal surgery, says Dr. Scott Adzick.

Every mother is not a fit for fetal surgery. Lori Howell, the executive director of the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment at CHOP, tells The Daily Signal that women who suffer from obesity, diabetes or high blood pressure are especially at risk.

“It is gut wrenching to say your health won’t permit us to do this,” Howell says.

Slim and fit, April met the criteria for fetal surgery. She decided to move forward with the procedure.

“There wasn’t a choice in our head,” April says. “We weren’t going to abort, and we weren’t going to let a tumor kill our child. We were going to do everything we could to save our child.”

Elijah survived the surgery, but his battle for life continued.

Surgeons exposed Elijah’s left arm from the womb to administer medicine. (Photo: Courtesy of April Leffingwell)

At 29 weeks, four weeks after the procedure, doctors noticed Elijah had a hole in his diaphragm, causing a hernia.

Still in April’s womb, Elijah’s stomach went into his chest and ruptured. His left lung collapsed.

The biggest risk of fetal surgery—premature birth—was now unavoidable.

A ‘Sick Little Boy’

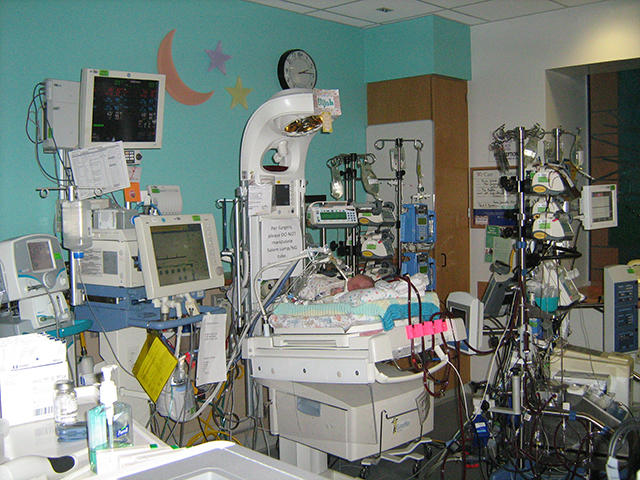

Born Nov. 19, 2012, at 33 weeks and six days old, April saw her son for only 10 seconds before Elijah was whisked away to the neonatal intensive care unit to be put on life support.

She did not get to hold him.

“I saw a sick little boy,” April says.

Days after Elijah is born, doctors monitor his brain activity. (Photo: Courtesy of April Leffingwell)

Elijah, who was born 5 pounds and 9 ounces, spent the first nine days of his life on life support.

An oxygen tube inserted into his trachea helped Elijah breathe.

“The big questions are: Will he have enough lung in the initial days and weeks—while the extra [lung] tissue is developing—in order to survive and oxygenate?” says Julie Moldenhauer, the medical director of the Special Delivery Unit at CHOP. “How long will he need oxygen support? The good thing with babies is that they can grow lung. Unlike adults, they can regenerate lung tissue to fill the void.”

April spent the first days after fetal surgery hot and weary from the two courses of steroids administered to her during the procedure.

Jason draped cold towels and rubbed ice over April.

After five days of recovery at the hospital, April resumed bed rest at the Ronald McDonald house.

When she wasn’t knitting and crocheting—which she learned to relieve boredom—April visited Elijah every day, staying until nighttime.

Jason, an engineer, worked remotely for 40 hours per week and would visit Elijah after his shift.

After Elijah was taken off life support, his father, Jason, read to him from the Bible. (Photo: Courtesy of April Leffingwell)

Jason and April ended up spending five months at Ronald McDonald.

April’s employer at the time, the financial firm Robert W. Baird, paid for their stay.

To make it feel like home, living amongst 20 other families, Jason and the other dads watched football.

The Leffingwells wore Green Bay Packers gear and Skyped into football watch parties that they normally would attend back home.

“We represented,” Jason says. “We all had a common bond. It was a great support network.”

Jason and April hosted Thanksgiving at Ronald McDonald. Both of their families attended. Elijah remained on life support at the hospital.

Elijah underwent two more surgeries before the family could return home. One surgery wrapped the top of his stomach around his esophagus to help stop food in his stomach from refluxing. The second put a hole and tube in his stomach, through which Elijah would be fed.

“These were all hidden underwater obstacles that reared their heads during the patient’s recovery,” Adzick says. “We had to solve each of those problems in sequence. The baby is a miracle in a way.”

At day of life 66, Elijah was discharged from the hospital, ready to cautiously explore the world.

‘Nothing Has Been on Time’

Except, for the first year of his life, Elijah couldn’t really find his way.

Constrained by the feeding tube, Elijah spent his days trapped in a chair, getting pumped with food.

He developed slowly.

“Nothing has been on time,” April says of Elijah’s progress. “But what is on time? He was born premature. So he’s always a few months behind.”

To make up for lost time in the womb, in December of last year, the Leffingwells travelled to Alexandria, Va., so Elijah could participate in a hunger-based weaning program to learn how to eat with his mouth.

The $12,000 cost of the program was not covered by insurance, but April and Jason raised the money through a YouCaring fundraising campaign.

The unusual therapy worked.

Elijah has been eating orally for a year.

Right to Life

Elijah may prefer veggies and sushi to chicken and pizza, but he still has normal cravings.

When a photographer tries to shoot Elijah’s back-to-chest scars, the boy is persuaded to lift his sweater with the enticement of M&M’s and 3 Musketeers.

Before Elijah crawls off April’s lap to reach the candy, he looks to Ellianna for approval—the rambunctious older sister looking out for a brother who she’s always known as sick.

When Ellianna, struggling to stay still for a photograph, pats her knees like a drum, Elijah mimics her.

Ellianna wildy flails her toes—shouting “crazy toes”—and Elijah follows.

Earlier, trying to find peace and quiet, Jason had asked Ellianna to watch Elijah alone in their shared bedroom.

“I need you to be a big sister,” Jason tells his daughter.

“Can we craft?” Ellianna counters. “I can help him cut.”

“No cutting,” Jason says.

During most of Elijah’s ordeal, Ellianna stayed with April’s parents.

Jason tells a story of when April’s mother shared with Ellianna how proud she was of the way the girl handled Elijah’s struggle.

“It has been hard,” Ellianna concurred knowingly to her grandma.

“She knew a lot,” Jason says of Ellianna’s understanding of Elijah’s experience. “She processed it immediately.”

Life figures to get easier for Elijah, but one can’t be sure.

Elijah, with April and Ellianna, is expected to be able to live a normal life. (Photo: Scott Eastman)

Doctors insist Elijah won’t have to live with any ill effects from his birth defect, cognitively or physically.

April says Elijah may need some skeletal restructuring in the future, depending on how his lung grows.

CHOP tracks Elijah’s progress through its pulmonary hypoplasia program, where doctors provide any needed follow-up to patients with lung conditions.

In September, the Leffingwells moved to the apartment in De Pere for Jason’s new job.

They are in the market for a house, where they hope Elijah will live for the rest of his childhood.

April plans to make a book about Elijah’s life through the nonprofit CaringBridge.

Elijah likely will write his own ending.

“He might not be able to play contact sports,” Jason says of Elijah’s future. “But who cares? Maybe he’ll be a musician. There’s other things in life he can do. Those are things I’ll be able to take pride in as a dad. I look forward to what Elijah will be able to do. Because he’s here for a purpose. For him to go through everything he has gone through, it isn’t for nothing.”