BioShield: Obama Diverted Funds From Its Fight Against Ebola, Other Threats

Melissa Quinn /

Seeking a more robust defense in the event of a bioterrorist attack on the United States, the Bush administration created a $6 billion fund to prepare the nation for such threats, including the deadly Ebola virus.

The Obama administration, however, has not used the range of tools and budget provided by the post-9/11 project, focusing instead on only three targets and diverting at least $1 billion to other priorities, a review by The Daily Signal found.

Nearly five years ago, in fact, the administration’s own biodefense science board warned that project funds “should not be diverted to support other initiatives, regardless of the merit of other purposes.”

Repeated diversions of funds “raise doubts about the intention of the U.S. government to consistently fund the enterprise,” the science board adds.

The government’s use of money from the program, Project BioShield, for other purposes also comes under question in a recent report prepared for Congress.

Oversight from lawmakers could help ensure the money is spent “in a manner consistent with congressional intent,” the report says.

Of $3.3 billion budgeted under Project BioShield over the past decade for medical countermeasures to Ebola and a dozen other “material threats” identified by the Department of Homeland Security, fully 90 percent — $3 billion — went to address only three: anthrax, smallpox and botulism.

>>> Those Ebola Vaccines in Testing Now? You Can Thank Dick Cheney for That

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. government put safeguards in place to protect the country from terrorists using chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapons.

This is the story of Project BioShield. Just one key initiative within the Department of Health and Human Services, the project had Ebola — among other sources of bioterrorism — in its sights for more than four years under President George W. Bush.

In September 2006, then-Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff called Ebola a “material threat against the United States population sufficient to affect national security.”

But the Obama administration decided to take Ebola off Project BioShield’s hit list even after President Barack Obama singled out the virus in his second official State of the Union address.

Products currently in development to combat Ebola are in early stages and thus cannot be funded through Project BioShield, an HHS spokeswoman told The Daily Signal.

No one could have predicted in 2010, perhaps, that more than 4,500 would die so far as a result of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa — or that four people would become infected in the U.S.

However, officials in both the Bush and Obama administrations clearly saw the potential threat in the deadly virus.

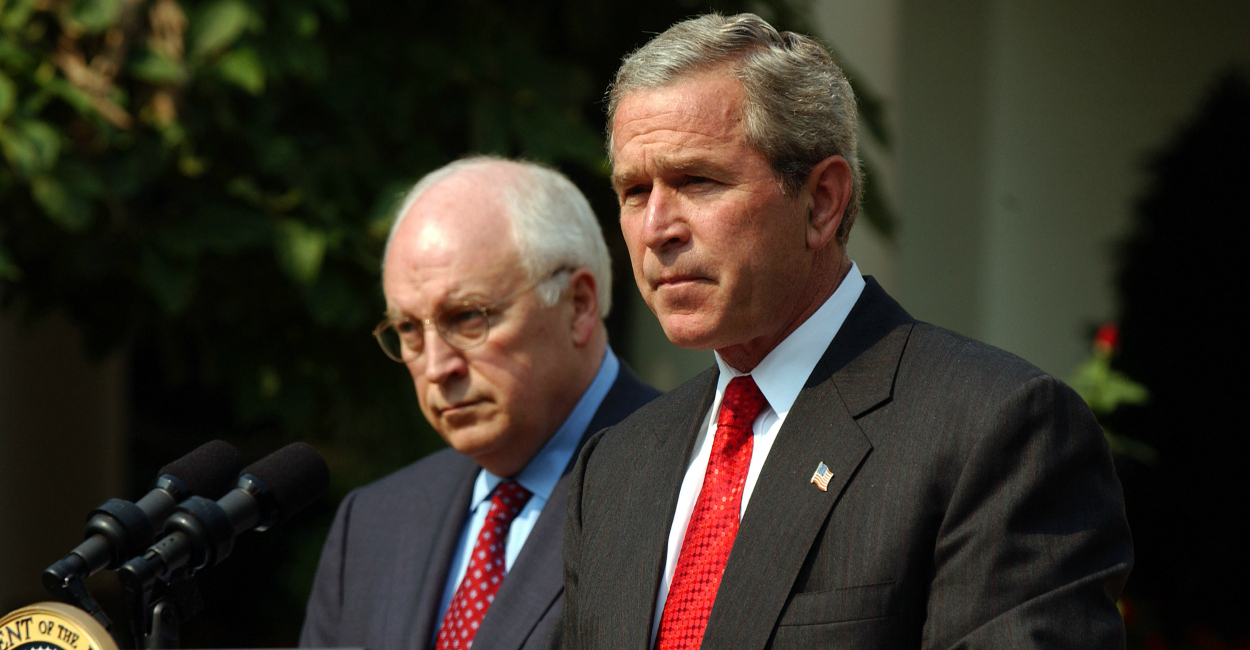

As vice president, Dick Cheney was the driving force behind Project BioShield. (Photo: The Heritage Foundation)

Creation of Project BioShield

In the wake of 9/11, Vice President Dick Cheney pushed for additional measures to protect the United States from bioterrorism.

Addressing his concerns, Congress passed a measure creating Project BioShield, an initiative spearheaded by Cheney. It allocated $5.6 billion to buy, develop and store drugs for use in the event of a bioterrorist attack.

>>> Ebola Preparedness: Yearning for Yesteryear

The law creating Project BioShield allowed the government to purchase vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics already in the advanced development phase.

It also gave the National Institutes of Health, specifically the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the authority to speed up and simplify the awarding of grants and contracts for developing medical countermeasures against bioterrorism.

Providing financial backing for research and development toward an Ebola vaccine doesn’t fall to one federal agency. Many agencies are in the fight against the virus, and those within HHS include the National Institutes of Health.

Both NIH and the Department of Defense have been instrumental in advancing Ebola treatments that now are in advanced stages and being used to care for infected Americans.

As part of Project BioShield, the fledgling Department of Homeland Security created during the Bush administration identified 13 material threats that were to be the focus of countermeasures. One of them was Ebola.

Pharmaceutical companies previously had little incentive to develop vaccines and therapeutics for viruses such as Ebola. Historically, Ebola specifically had killed far fewer people — roughly 1,500 since the disease’s discovery in 1976 — than it has in the current outbreak in West Africa.

Cheney’s Project BioShield, though, gave companies a financial incentive to get going and guaranteed them a customer: the U.S. government.

“While not ‘perfect’ protection, BioShield is the best program [of its type] America has,” Steven Bucci, a national security and foreign policy expert at The Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Signal.

Bucci, a top Defense Department official during the Bush administration, added:

It provides a layer of defense that should improve every day it is deployed and as we learn more. If it is left fallow, that layer of defense will not improve, and we will become more vulnerable every day.

From 2004 to 2013, funding for Project BioShield was about $560 million a year. When the original 10-year funding designation expired, Congress passed a measure — the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act of 2013 — that authorized up to $2.8 billion for BioShield from 2014 to 2018.

In the year since the original 10-year appropriation expired, Obama has sought significantly less than the original authorized annual funding. He requested $250 million for fiscal 2014 and $415 million for fiscal 2015.

In the first 10 years, Congress opted to rescind or transfer approximately $2.3 billion that had been designated for countermeasures to agents of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear terrorism.

Congress rescinded $25 million from Project Bioshield, according to a June report from the Congressional Research Service. The lawmakers transferred $137 million for influenza preparedness and another $304 million for basic research on biodefense and emerging infectious diseases (including Ebola) at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of NIH.

The report said the lawmakers also transferred $1.8 billion to the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, the sub-agency of HHS that oversees Project BioShield contracts.

Over the years, Project BioShield provided roughly $3.3 billion to acquire medical countermeasures against material threats such as Ebola.

The Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act, passed last year by Congress, re-upped funding for Project BioShield through 2018. It also gave authority to the HHS secretary to move up to half of that four-year funding, or $1.4 billion, to BARDA in a single year.

In the Congressional Research Service report examining related issues, science and technology policy specialist Frank Gottron questions the government’s use of BioShield funds for other purposes.

“Congressional oversight of such transfers could help ensure that HHS uses Project BioShield appropriations in a manner consistent with congressional intent,” Gottron writes.

>>> ‘A Little Like a War:’ He Treated Ebola in Africa, Now Helps Prepare at Home

President George W. Bush credited Vice President Dick Cheney with advancing the nation’s readiness for biological threats such as Ebola. (Photo: Roger L. Wollenberg/Newscom)

Project BioShield and the Bush Administration

From its creation in 2004 until President Bush’s departure from office in January 2009, Project BioShield’s authority was the basis for research and development of several Ebola treatments.

A review of HHS annual reports turns up multiple grants awarded to companies specifically to research Ebola.

From 2004 to 2006, under BioShield authorities, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases awarded more than $1.8 million in grants to Apath LLC and Oncovir Inc. to develop antiviral drugs for Ebola infection and advance early treatment of the virus, respectively.

Asked about these two projects, HHS spokeswoman Elleen Kane told The Daily Signal that funding may have been discontinued, since subsequent reports did not mention them. Kane directed inquiries to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which did not respond.

Chertoff’s designation of Ebola as a national security threat eight years ago was the basis for a declaration from HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell three months ago authorizing use of in-vitro diagnostic tests to help detect the virus.

In its annual report for 2007-08, HHS stated it had invited proposals for development of an Ebola vaccine, a request made possible by Project BioShield.

Similarly, an experimental Ebola vaccine from Johnson & Johnson benefited from BioShield backing. In 2008, NIH awarded a grant worth about $30 million to a biopharmaceutical company called Crucell, which Johnson & Johnson later purchased.

According to Crucell’s website, Project BioShield was part of the rationale for developing a vaccine.

>>> NIH Director Warns of Consequences from Mandatory Quarantines in NY, NJ

Project BioShield and BARDA

The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the agency within HHS that oversees Project BioShield, was created in 2006 under President Bush.

With its attachment to BARDA, the balance of BioShield’s 10 years of advanced appropriations became known as the Special Reserve Fund.

BARDA sought to “facilitate the research, development, and acquisition of medical countermeasures for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear agents …,” the agency’s draft strategic plan states. It continues:

With NIH basic research and development programs, the newly established BARDA advanced development funding mechanisms, the acquisition support available through the Project BioShield Special Reserve Fund, DSNS assets [a reference to the Centers for Disease Control’s Division of Strategic National Stockpile], and appropriations for pandemic influenza countermeasures, HHS now has a comprehensive, end-to-end capability to facilitate the successful advanced development, procurement, and availability of medical countermeasures to increase public health preparedness for responding to chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats and emerging infectious diseases, including pandemic influenza.

BARDA’s first strategic plan did not outline plans to combat Ebola.

In the agency’s 2011-16 strategic plan, however, BARDA Director Robin Robinson specifies Ebola as an emerging threat. Robinson, appointed in 2008, outlines a goal to develop capabilities to “address novel and emerging threats.”

The report says:

The Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act charges BARDA with the advanced development of medical countermeasures for emerging infectious disease threats, which come in many forms. New and lethal infectious diseases, such as MRSA, Dengue, Ebola, SARS, and Nipah virus, continue to emerge in nature.

Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., was and continues to be a vocal proponent of BARDA and Project Bioshield. Of the role the authority plays in protecting America, Burr told The Daily Signal:

This [Ebola] outbreak reminds us of the human toll the threats we face can take and why we must fully leverage all of the tools at our disposal to quickly advance the medical countermeasures we need to protect the American people. … Congress put in place critical tools, which we must fully implement and leverage if we are going to be prepared for the full range of threats we may face.

>>> Here’s Why Budget Cuts Have Nothing to Do with Developing an Ebola Vaccine

In 2010, President Obama and HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius both spoke of the threat posed by the Ebola virus. (Photo: Jim Lo Scalzo/Newscom)

Project BioShield and the Obama Administration

In his 2010 State of the Union address, after a year in office, President Obama announced an initiative to “give us the capacity to respond faster and more effectively to bioterrorism or an infectious disease — a plan that will counter threats at home and strengthen public health abroad.”

Two months later, HHS’s National Biodefense Science Board evaluated a relevant interagency group and made recommendations. The interagency group, called the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise, oversees BioShield and other efforts to address the government’s need for measures to protect America from chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats.

In its March 2010 report, the National Biodefense Science Board called for reauthorization of BioShield, specifying that it should be “adequately funded.” The science board said the “funds should not be diverted to support other initiatives, regardless of the merit of other purposes.”

The report goes on to list instances where BioShield money was diverted to other projects in 2009 and 2010, the first two years of the Obama administration. It says:

Setting aside the merits of other funding targets, repeated diversions of the Special Reserve Fund raise doubts about the intention of the U.S. government to consistently fund the [medical countermeasures] enterprise over multiple years. Transfers from the [fund] to other entities must be avoided if industry confidence in the U.S. government as a partner is to be fostered.

Congress did allocate more funding to Project BioShield — $2.8 billion through 2018 — but the Obama administration and lawmakers continue to divert money for other purposes, some unrelated to the mission. The Congressional Research Service addressed that concern in its June report on BioShield to Congress.

Five months after the science board’s recommendations, in August 2010, then-HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius delivered a speech marking release of an HHS examination of the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise, the interagency group.

>>> Heading to the Doctor or Emergency Room? Prepare to Be Pre-Screened for Ebola

Sebelius announced a plan creating, among other things, a “strategic investment fund” for new countermeasure technologies.

Joined by Anthony Fauci, director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and Robinson, the BARDA director, Sebelius specifically addressed the government’s increased focus on medical countermeasures.

She cited a potential Ebola outbreak as cause for due diligence in developing such measures:

Right now, there’s little incentive for private companies to produce medical countermeasures for rare conditions, like Ebola virus or exposure to non-medical radiation. And yet, in the event of an Ebola outbreak or nuclear explosion, these countermeasures would be critical.

The goal of the HHS plan, Sebelius said, was to “add more life-saving products to the pipeline, enabling critical programs like BioShield to work the way they are supposed to.”

According to HHS annual reports on Project BioShield, however, the Obama administration hasn’t used any of the initiative’s funds to back grants for development of an Ebola vaccine.

In fact, in its June report, the Congressional Research Service points to “countermeasure prioritization” as an issue for Congress to consider.

“The Project BioShield contracts have not been used to acquire countermeasures against all of the material threats determined by DHS,” the report says, referring to the Department of Homeland Security.

>>> States Have Legal Authority to Quarantine Citizens Exposed to Ebola

Of the total $3.3 billion budgeted for medical countermeasures from 2004 to 2014, 90 percent, or $3 billion, went to address just three threats: anthrax, smallpox and botulinum (which can cause botulism).

No countermeasures funding went to the remaining 11 chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats identified by the Department of Homeland Security, including Ebola.

“It does not matter if the threatening pathogen is a natural one like Ebola is today, or a weaponized one from some former Soviet scientist, we need to constantly upgrade our defenses,” Heritage’s Bucci said. “Failing to make that investment is just wrong.”

In September and October, though, the Obama administration did authorize funding under BARDA to develop two Ebola vaccines as the outbreak spread throughout West Africa and four people in the U.S. were diagnosed with the disease.

“The Ebola outbreak in West Africa underscores how medical and public health preparedness and response programs, especially BARDA’s medical countermeasure work, are a matter of national security,” Burr said. “It’s not enough to prioritize this work only in the matter of crisis.”