A Voter’s Guide to Untangling the ‘Jungle’ Election That Could Keep America Waiting

Kelsey Bolar /

America’s political operatives are spread across the land fighting for their candidates, from the frosty U.S. Senate race in Alaska to the red-hot governor’s race in Florida.

But if control of the Senate hangs in the balance after Tuesday’s midterm elections—and multiple scenarios suggest it could—then most of those operatives will be bound for Louisiana after the polls close.

The Bayou State doesn’t have party primaries. All candidates from all parties run in a “jungle primary,” which is what’s on tap Nov. 4. If none of the eight candidates for Senate garners more than 50 percent of the vote, the top two must compete in a runoff election Dec. 6.

So Louisiana’s Senate race is unlikely to be decided Tuesday.

According to the most recent polling, incumbent Democrat Mary Landrieu, whose father served as mayor of New Orleans and whose brother is mayor now, sits at about 38 percent of the vote.

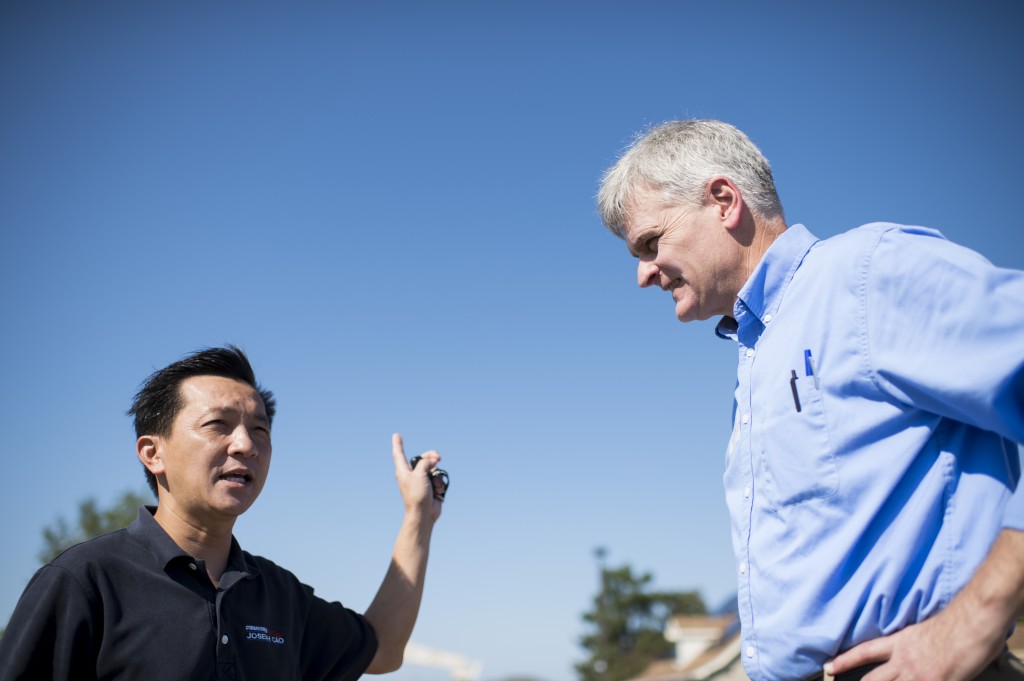

Bill Cassidy, a Republican congressman from Baton Rouge, is just behind at 34 percent. And Rob Maness, a retired Air Force colonel from Madisonville with enthusiastic tea party backing, comes in third at 9 percent.

Lay of the Land

Louisiana’s election system dates to the 1970s, when the state’s Democratic Party ran the ideological gamut and statewide elections would pit one Republican against eight or nine qualified Democrats.

The system was designed to ensure the two strongest candidates got on the final ballot, even if they were of the same party.

Today, with many of the conservative Democrats having switched to the Republican Party, the situation often is reversed. There are eight candidates for Senate on the ballot: four Democrats (Wayne Ables, Vallian Senegal and William Waymire Jr. are the other three), three Republicans (Thomas Clements is the third) and a Libertarian, Brannon Lee McMorris.

It’s fair to say that Landrieu, who most consider the only serious Democratic candidate, is not having a smooth ride.

Like many Democratic hopefuls, incumbents or not, Landrieu is struggling to distance herself from the increasingly unpopular President Obama.

Landrieu, 58, supported Obama on issues ranging from spending $800 billion in “economic stimulus” to remaking the U.S. health care system under the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.

Obama didn’t carry Louisiana in either 2008 or 2012, and is even less popular there now. Landrieu also is viewed as having become aloof from the state and more a creature of Washington, D.C.

One ad by an outside group shows District Mayor Vince Gray calling Landrieu a citizen of Capitol Hill, where she has a $2.5 million townhouse, and referring to her as the District’s senator because of all she has done for his city.

Landrieu also came under attack for using taxpayer money to cover campaign flights and for listing that townhouse as her residence on a statement of candidacy filed in January.

Cassidy, 57, a medical doctor who practiced in the state’s charity hospital system, fits the pattern of what many conservatives today call an establishment Republican. He campaigns on health care reform and energy policy, and he enjoys the support of most of the party machinery—statewide and nationally.

Cassidy is a three-term congressman with a slew of endorsements, from the Susan B. Anthony List and the National Rifle Association to former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Texas Gov. Rick Perry, and Louisiana Sen. David Vitter.

Given his close ties to Vitter, a conservative eying governorship in the state, some experts say it is “interesting” that Cassidy is cast as an establishment Republican.

“If there is any one GOP politician in Louisiana [who] Cassidy owes a debt of gratitude to, it’s David Vitter,” says Jeremy Alford, a syndicated columnist in Louisiana, adding:

David Vitter very early on convinced a number of movers and shakers not to run for the U.S. Senate, so he cleared the field for Cassidy. He allowed a member of his staff to run his campaign [and] he was instrumental in getting major players to Louisiana, like [Sen.] John McCain, to campaign for Cassidy.

Maness, who served 32 years in the Air Force but never has held public office, has run a solid and energetic campaign. He visited all 64 parishes, putting more than 80,000 miles on his pickup truck.

By late September, Maness, 52, had gained real momentum. His dogged work and hard line on liberty as well as fiscal, defense and energy issues make him a darling of tea party conservatives.

With endorsements from prominent organizations such as the Senate Conservatives Fund, public figures such as Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, and former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, plus talk show giant Mark Levin, Maness became a serious contender.

Maness also has struck the right notes in this year of voter discontent, positioning himself as an alternative to the “career politicians” he says don’t always put Louisiana’s needs first.

Navigating the Jungle

Folks associated with the Cassidy campaign describe Maness as “this political fly they just couldn’t swat away from their face,” says Alford, publisher and editor of LaPolitics.com and LaPolitics Weekly.

“They wish they could have spent 100 percent of their efforts on Landrieu, rather than having to look over their shoulders wondering exactly what Maness is doing.”

Some Republicans fear Maness could spoil the race and give victory—and possibly control of the Senate—to Landrieu and the Democrats. But this is unlikely under the jungle system.

“There’s definitely a feeling that Maness, by staying in this race, is a spoiler; that Cassidy could have had a good shot of building ahead of steam to capture victory in the primary,” says Alford.

But when it only costs $900 for candidates to enter the jungle primary, even the favorites will have competition. This year, eight Senate hopefuls put their name on the ballot.

Until a few weeks ago, most voters had only heard of two — Cassidy and Landrieu.

But with the help of prominent backers, Maness shook things up. Some hope he will be the next David Brat — the underdog who ousted House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in Virginia’s Republican primary, to the surprise of political gurus of all sorts.

If the race winds up as polls project and Cassidy then can shore up support among Maness voters, he could claim the seat from Landrieu.

Political prognosticator Charlie Cook, a native of the state, lists the race as a toss-up, and the Real Clear Politics average of polls gives Cassidy a 4.5-point lead over Landrieu head to head.

>>> Watch Senate Hopefuls Score Performance of Obama, Jindal in One Sentence

Come as You Are, Leave Different

Louisiana isn’t like most other states. It has parishes instead of counties. It has gumbo instead of soup. It is alone among the states — and joined only by Quebec in all of North America — in basing its laws on the Napoleonic Code rather than the English common law system.

The state’s Democrats are sometimes as conservative as its Republicans. Its voters tend to reward the flamboyant over the substantive. And its politics this year is further complicated by a love-hate relationship with the Republican governor, Bobby Jindal.

Yet, the math seems simple enough. Landrieu appears unlikely to get much more than her current 38 percent. Cassidy has 34 percent now. He presumably would get most of the 9 percent who support Maness and probably enough from the minor candidates to prevail.

But, as is usually the case with Louisiana politics, it’s not that simple.

Geoff Skelley, associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia Center for Politics, says tensions between the two Republican candidates reflect the divide between mainstream and tea party Republicans.

>>> 9 Senate Races That Could Tip the Balance of Power

And that could be a problem for Cassidy among more conservative elements of the electorate.

“In this polarized era, more conservative Republicans are loathe to back GOP candidates they consider to be even somewhat moderate, though given Louisiana’s Democratic past, many Democrats-turned-Republicans exist and do well in elections,” Skelley told The Daily Signal, adding:

While Cassidy’s voting record has been conservative during his time in Congress, he’s not known for being a rabble-rouser or for making strong denunciations of the Obama administration. Given his demeanor and Democratic roots, some tea partiers are suspicious of his conservatism.

Stay or Get Out?

This explains why establishment Republicans keep suggesting Maness could make matters easier by getting out and giving Cassidy a chance to win outright Tuesday.

Maness told The Daily Signal that isn’t going to happen.

“Our goal is to put America back on track,” he says, adding:

I happen to be a life-long Republican, I’m running on the Republican Party’s platform [and] I wish the party was joining us because their base and my candidacy are all about their platform because we believe in it.

Cassidy’s team would not respond to The Daily Signal’s requests for an interview, or even a comment.

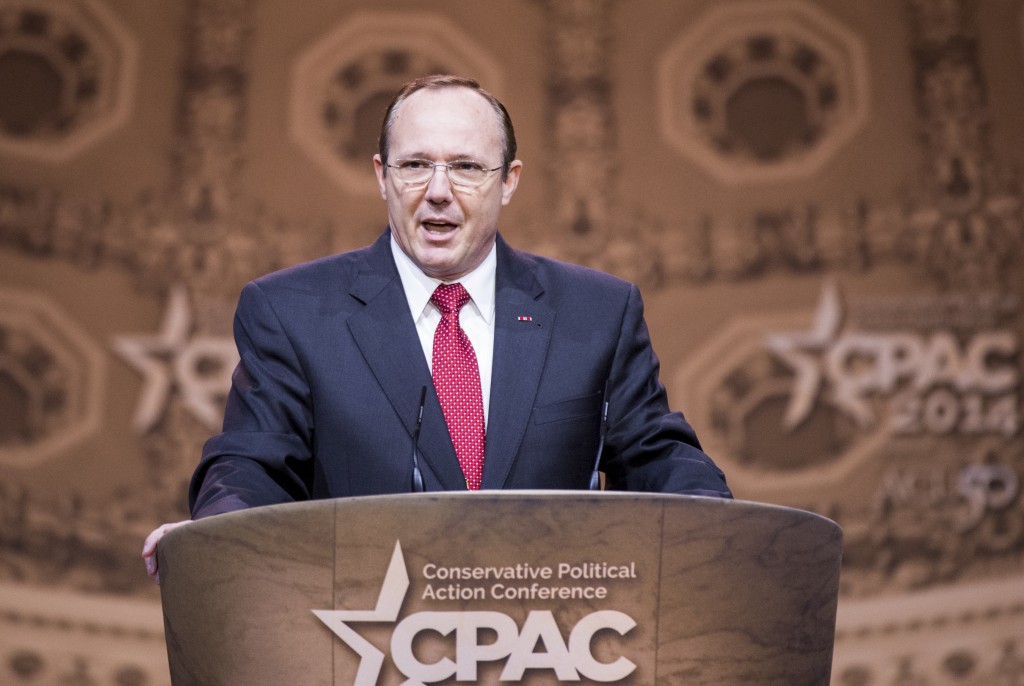

But Gaston Mooney, executive director of Conservative Review and longtime Republican policy adviser, says Maness is right to ignore establishment calls to drop out.

“Landrieu is in a freefall, so it’s no surprise that the Washington political establishment has begun orchestrating more calls for Maness to drop out,” Mooney says, adding:

With this race looking more winnable for conservatives, this split-the-vote scare tactic is all the establishment has left to throw at Maness. With Landrieu nowhere near the 50 percent needed, it makes these calls even more ridiculous.

Louisiana’s jungle primary provides “the purest example of candidates across the spectrum,” Mooney says, but “the establishment is fearful of that type of referendum vote.”

The End Game

Although Skelley says support for Maness “hasn’t dissipated,” a David Brat-like finish is becoming more far-fetched.

On Monday, his former campaign manager attacked Maness’s loyalty to the tea party, calling the retired colonel a “political opportunist.”

“He tries to adapt to different groups,” said John Kerry, who managed Maness’ campaign for six months in 2013. “He made it very clear, ‘I’m not a tea partier. I don’t want to be known as a tea party candidate.’ Then, he learned that was the only way he was going to get funds.”

Kerry sent his email, obtained by the Associated Press, to political activists and community leaders. Kerry claims he isn’t affiliated with the Cassidy campaign or any organization supporting him.

The Maness campaign calls the claims ridiculous.

Even if the claims have some legs, Skelley says, because Maness has yet to cut deeply into Cassidy’s position as the leading Republican, a Cassidy-Landrieu runoff Dec. 6 is “pretty certain.”

But when he gets there, conservatives could take some convincing, Skelley stresses:

Cassidy is going to have about a month to shore up his support among Maness’s backers, a not-insignificant chunk of the electorate, to help him defeat Landrieu.

Brian McNicoll contributed to this report. It has been modified to correct an error in the description of the field of Senate candidates.