China’s Slowdown Not Good for the Global Economy or the U.S.

William T. Wilson /

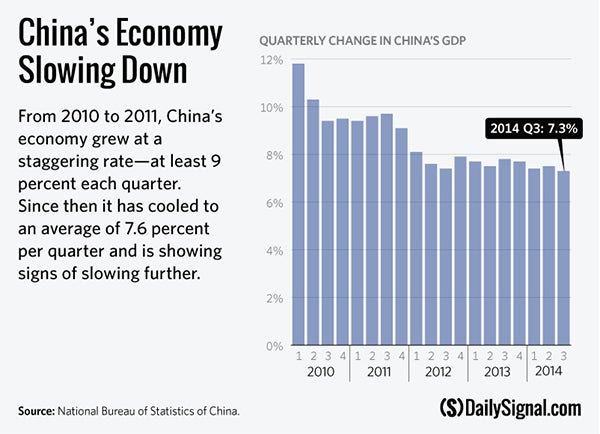

China announced on Tuesday that third quarter gross domestic product (GDP) growth had slowed to 7.3 percent, the slowest since the 2008–2009 global recession. This slowdown means that Beijing will most likely fail to meet its annual growth target of 7.5 percent for the first time since 1998. With the U.S. and China at odds over so many issues from elections in Hong Kong to freedom of the seas to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, it is tempting to cheer its ever-more-sobering economic environment. But China’s slowdown is not good for the global economy, which means it’s not good for the U.S.

According to the Financial Times, most alternative indicators of growth such as electricity consumption, credit expansion, and railway freight traffic have also been weak. Economists expect Chinese growth to continue slipping in the coming months. Growth would have been even slower without the economic stimulus package passed earlier in the year.

The primary cause of the continued slowdown is the real estate market, which is now spreading to other sectors. Steel and cement production is falling along with the production of white goods (refrigerators, stoves, etc.). More ominously, the profits of private industrial enterprises collapsed in the third quarter, which will likely impact the shadow banking system for which it heavily lends.

While 7 percent growth would be coveted by most developing countries, China has long claimed that it needs 7 percent growth to create the 10 million jobs each year for its massive population.

China’s continued slowdown should be of major concern for much of the world, particularly if the slowdown accelerates. According to The Wall Street Journal, China’s contribution to global growth has more than tripled to 34 percent this decade from 10 percent in the 1990s. The U.S. contribution has fallen to 17 percent from 32 percent in the 1990s.

China is the world’s second largest importer and has strong trade links with many emerging economies, which have seen their average growth drop to 3 percent from 6 percent in 2010. China’s slowdown is the primary reason for the drop in commodity prices, including oil, which has fallen by more than 20 percent since last summer. Commodity producers Russia and Brazil are in recession. Australia’s economy has been struggling.

Much of China’s past growth has been fueled by rapid increases in debt that are not sustainable. The question then is what happens to global activity if China slows significantly. According to a recent J. P. Morgan analysis, every 1 percent slowdown in China’s growth reduces global growth by one-half of a percent, so a 2 percent slowdown would reduce an already jittery global economy by a full percentage point.

China’s broken state-led model of capitalism is in the early stages of getting its comeuppance, and when China sneezes, the rest of the world gets a cold.