Is School Choice Feasible in Rural States?

Lindsey Burke /

School choice is now a reality for children in 24 states and Washington, D.C. They take advantage of some 40 options ranging from tuition scholarships to education savings accounts. Although states across the country have embraced school choice, rural states have done so more slowly, in part, say some, out of a belief that choice won’t work effectively in those communities.

A piece published earlier this week perpetuated the notion that school choice is a non-starter for rural states. In a YEP [Young Education Professionals] DC article, Matt Richmond writes:

Rural communities, regardless of the country, have a much harder time attracting the kind of resources necessary to benefit from increased ‘choice.’ Often times, a decreased government presence means fewer good choices and a decrease in quality of (affordable) options. In these cases, the market does not improve the situation; it only makes things worse. Consider rural school districts today: Many are faced with small (and shrinking) budgets, have a difficult time attracting and retaining quality staff, are burdened with large transportation costs, and have very little support from community organizations. Their largest challenges are tied to lack of connectedness to resources and economies of scale. Reducing the government’s role and introducing competition to that environment will only exacerbate current problems…

Richmond isn’t the first person to be skeptical of the promise of school choice in rural areas. But are these assertions well-founded?

First, difficulty finding and retaining quality staff in rural areas actually could be alleviated with the introduction of choice, namely through virtual charter schools. Small rural schools, for example, are the least likely to offer Advanced Placement courses (only 34 percent of such schools do so, according to a 2008 analysis by the College Board). Enabling statewide virtual charter schools to operate could mean the difference between hundreds of high school students taking AP Calculus or Physics courses, versus having to be content with what’s available in their small brick-and-mortar school – which is unnecessary in an era when the ubiquity of the Internet has improved access to services and products in almost every other sector.

In addition to charter laws enabling online learning to flourish in rural communities, the introduction of choice also could herald improvements in the traditional public school system. Richmond writes that competition “will only exacerbate current problems.” But research on the impact of choice on student learning found competitive pressure from growing school choice programs improves academic outcomes for those who take advantage of choice programs and those who remain in public schools.

And what of the claim that rural communities have a harder time attracting the resources to benefit from choice? As Milton Friedman pointed out, public schooling does not have to be delivered in public schools. Enabling funding to follow children to a school of their parents’ choice would enable a thriving private market to operate. Policymakers in rural states can rest assured supply would meet demand if dollars were student-centered and portable.

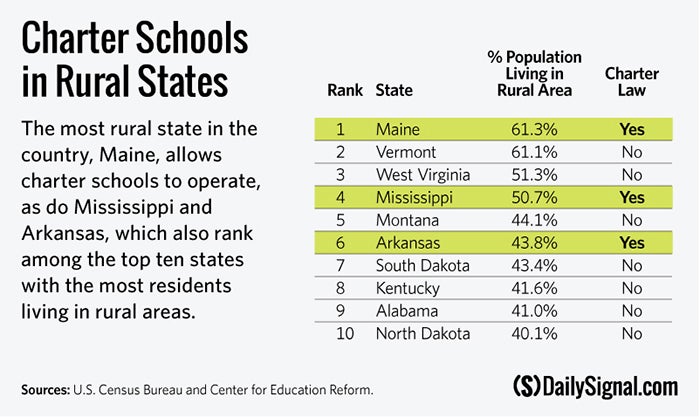

Not only will supply meet demand, but the education funding landscape should be flexible enough for a future that could bring new jobs and families to rural communities. If the Keystone pipeline is ever built, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana would be wise to have the legislative framework in place to allow charter schools and other innovative options to provide education to the influx of people who will move there.

As for transportation, might self-driving cars make that a moot point? “California, Nevada and Florida made it legal to operate self-driving cars on public roads two years ago. Google’s fleet has since traversed more than 435,000 miles in cities and on highways without causing an accident,” notes L. Gordon Crovitz in the Wall Street Journal.

The Cato Institute’s Jason Bedrick smartly envisions how the introduction of driverless cars—a not-so-distant reality—could change the game for accessing schools of choice. “It’s impossible to know all the ways that the advent of self-driving cars will transform society, but the great potential for saving lives, improving efficiency and expanding educational options is cause for excitement. Combined with educational choice programs, a society in which all children have access to hundreds of educational options may soon be a reality,” Bedrick writes in EducationNext. Self-driving cars could, for instance, help students access the 123 private schools in Montana.

In their excellent assessment of why rural communities need school choice, Andy Smarick and Ellie Craig point out that rural communities just aren’t that rural anymore:

Rural America is larger and more diverse than many might assume. A ‘rural’ area is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as a population, housing, and territory not included within an urban area. An urban area contains 50,000 or more people. By those measures, about one in four U.S. students live in rural communities.

Rural families need options like everyone else. Perhaps even more so in an environment where access to Advanced Placement courses or physics or Spanish might be limited by a shortage of course options and teachers with certain content matter expertise. Statewide online charter schools can be game-changers in that regard, but states have to allow them to operate first. And while they’re at it, allow all financing mechanisms designed to advance choice in education—vouchers, tuition tax credits, education savings accounts—to become a reality.