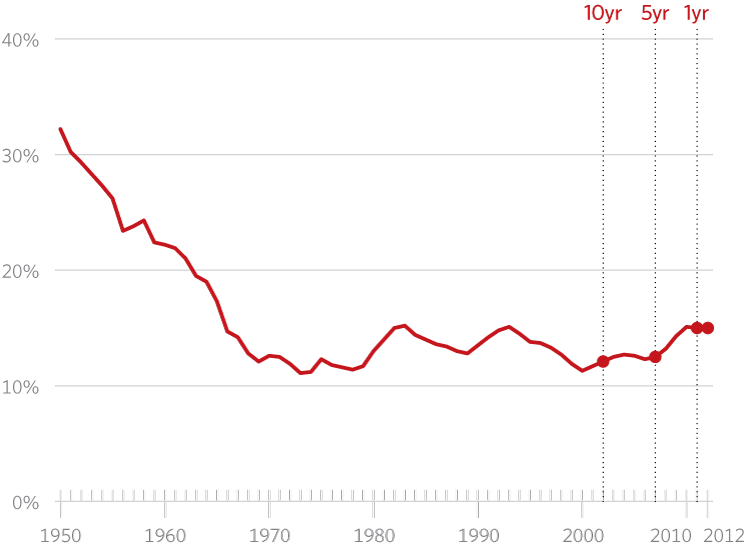

This Chart Proves the War on Poverty Has Been a Catastrophic Failure

Robert Rector /

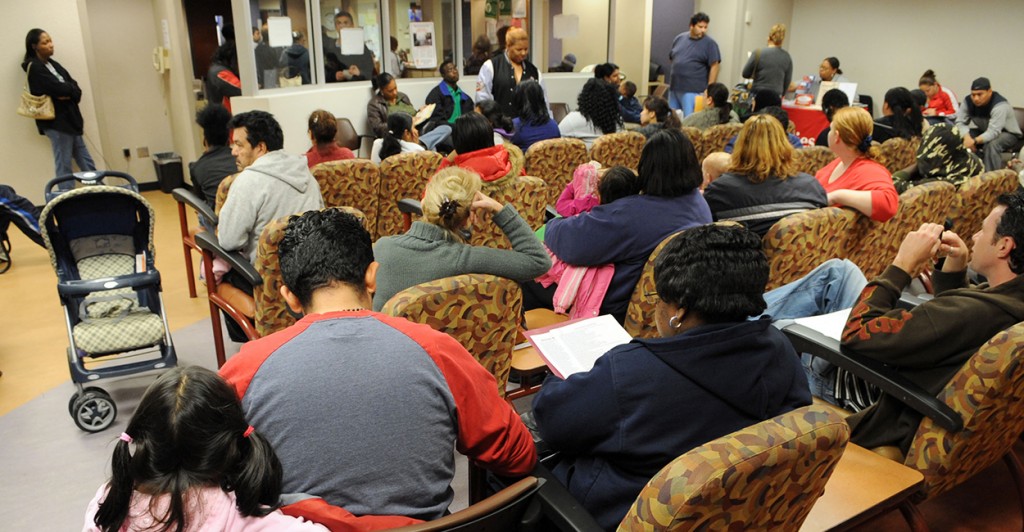

People wait in line to apply for benefits at the Gwinnett County Department of Family and Childrens Services.This office has been so overwhelmed by applicants that the fire marshall had to close it down one day. (Photo: © Erik Lesser/ZUMAPRESS.com)

For the past 50 years, the government’s annual poverty rate has hardly changed at all. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 15 percent of Americans still live in poverty, roughly the same rate as the mid-1960s when the War on Poverty was just starting. After adjusting for inflation, federal and state welfare spending today is 16 times greater than it was when President Johnson launched the War on Poverty. If converted into cash, current means-tested spending is five times the amount needed to eliminate all official poverty in the U.S. How can the government spend so much while poverty remains unchanged?

>>> For more articles like this, check out the 2014 Index of Culture and Opportunity

The answer is simple: The U.S. Bureau of the Census official “poverty” figures are woefully incomplete. The Census defines a family as poor if its annual “income” falls below specific poverty income thresholds. In counting “income,” the Census includes wages and salaries but excludes nearly all welfare benefits. The federal government runs over 80 means-tested welfare programs that provide cash, food, housing, medical care, and targeted social services to poor and low-income Americans. Government spent $916 billion on these programs in 2012; roughly 100 million Americans received aid from at least one of them, at an average cost of $9,000 per recipient. (These figures do not include Social Security or Medicare.)

Of the $916 billion in means-tested welfare spending in 2012, the Census counted only about 3 percent as “income” for purposes of measuring poverty. In other words, the government’s official “poverty” measure is not helpful for measuring actual living conditions.

On the other hand, the Census poverty numbers do provide a very useful measure of “self-sufficiency”: the ability of a family to sustain an income above the poverty threshold without welfare assistance. The Census is accurate in reporting there has been no improvement in self-sufficiency for the past 45 years.

Ironically, self-sufficiency was President Johnson’s original goal in launching his War on Poverty. Johnson promised his war would remove the “causes not just the consequences of poverty.” He stated, “Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.” Johnson did not intend to put more Americans on the dole. Instead, he explicitly sought to reduce the future need for welfare by making lower-income Americans productive and self-sufficient.

By this standard, the War on Poverty has been a catastrophic failure. After spending more than $20 trillion on Johnson’s war, many Americans are less capable of self-support than when the war began. This lack of progress is, in a major part, due to the welfare system itself. Welfare breaks down the habits and norms that lead to self-reliance, especially those of marriage and work. It thereby generates a pattern of increasing inter-generational dependence. The welfare state is self-perpetuating: By undermining productive social norms, welfare creates a need for even greater assistance in the future. Reforms should focus on these programs’ incentive structure to point the way toward self-sufficiency. One step is communicating that the poverty rate is better understood as self-sufficiency rate—that is, we should measure how many Americans can take care of themselves and their families.