Price to Avoid Another Benghazi? House Leaders Question $461 Million Training Center

Josh Siegel /

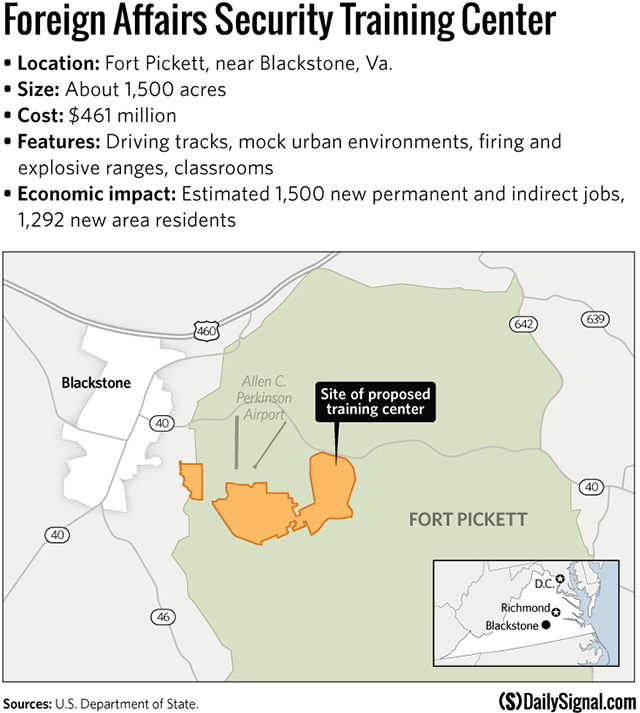

With the deadly Benghazi attacks providing impetus and momentum, the State Department announced this spring that it will build a $461 million training center for diplomatic security personnel in rural Virginia. The move, however, comes after congressmen with oversight responsibility asked unanswered questions about the project and suggested the Obama administration could accomplish the goals by spending tens of millions of dollars less.

The Foreign Affairs Security Training Center, years in the making, would consolidate similar training operations in one place.

To be built on 1,500 acres of public land that was home to the Fort Pickett Army National Guard in Blackstone, Va., the security training center is supposed to look and feel like a real U.S. embassy surrounded by urban-style streets, buildings, and facades, State Department officials announced in April.

Some 10,000 students per year will practice shooting on firing ranges, driving at high speeds on race tracks, and detecting improvised explosive devices.

It’s the kind of facility that not only might help repel the sort of terrorist attacks that overwhelmed the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, on Sept. 11, 2012, but also prepare security teams for situations such as the current advance of Islamist insurgents on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.

Burned-out cars at the gate of the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya. (Photo: AFP/Getty Images/Newscom)

But according to letters obtained by The Daily Signal, the State Department’s enthusiasm for the project at Fort Pickett is not shared by House committee chairmen, who say the Obama administration approved the $461 million plan without answering questions they raised about ways to achieve security improvements while spending nearly $200 million less.

The Foreign Affairs and Homeland Security committees, the chairmen wrote to top administration officials, “have a responsibility to ensure that funds are invested wisely.”

The Georgia Option

In a series of letters beginning in December 2013, Republicans Edward Royce of California, Michael McCaul of Texas, and Jeff Duncan of South Carolina pushed the White House Office of Management and Budget to consider less expensive alternatives.

The House also included specific language in a bipartisan bill to require the Obama administration to conduct an independent feasibility study comparing the Fort Pickett plan with other options.

A spokesperson for the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security told The Daily Signal that the agency, in conjunction with the U.S. General Services Administration, reviewed more than 70 sites before deciding on several parcels on the Fort Pickett property straddling Chesterfield and Nottoway counties.

The Republican lawmakers focus on one particular rejected alternative in their letters to OMB: The Department of Homeland Security’s offer to expand its Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Ga.

The Georgia facility already has lodging, weapons ranges, and driving tracks among other features that meet State’s needs, wrote Royce, chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs; McCaul, chairman of the Committee on Homeland Security; and Duncan, chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Management Efficiency.

‘Responsibility to invest wisely’: House Foreign Affairs Chairman Edward Royce, R-Calif. (Photo: Mandy Cheng/AFP/Getty Images)

DHS officials estimated that upgrading the Georgia center would cost $272 million, about $189 million less than the Fort Pickett plan.

Across its training centers, which include locations in Artesia, N.M., and Charleston, S.C., DHS already hosts 91 federal agencies. Many of those agencies are based in Washington, and their employees travel to Glynco, Ga., via the Brunswick Airport, which is less than two miles away.

Peggy Dixon, a public affairs specialist at the training center in Glynco, referred The Daily Signal to DHS in Washington. A spokesman there declined comment.

Unanswered Letters

The Fort Pickett plan is hailed as a job creator by two Republican congressmen whose districts are affected, Reps. Robert Hurt and Randy Forbes, as well as by three prominent Democrats elected statewide: Gov. Terry McAuliffe and Sens. Tim Kaine and Mark Warner.

While acknowledging the importance of training for embassy and other diplomatic personnel, House committee chairmen Royce, McCaul, and Duncan portray the Fort Pickett plan as redundant and unnecessary.

Five months ago the three chairmen wrote Sylvia Mathews Burwell, then OMB director, to reiterate their request for an outside study comparing the Georgia option with Fort Pickett.

“We are concerned by the widely differing cost estimates provided by State and DHS to satisfy State’s security training needs,” the chairmen wrote to Burwell on Jan. 9. “We encourage you to analyze the reliability of the data provided by both agencies to help the administration’s decision.”

Staff members for the House Committee on Foreign Affairs say Burwell, who took over this month as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, did not respond.

Burwell also did not reply, the staffers say, to a May 19 letter written after the State Department announced it would build the training center at the Fort Pickett site.

In that letter, also addressed to Secretary of State John Kerry and DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson, Royce and McCaul ask to review the results of the OMB study of options and to be briefed on the Obama administration’s decision.

The congressmen have yet to be briefed, and the committee staffers say they wonder whether OMB actually conducted the analysis.

As OMB chief, Sylvia Mathews Burwell didn’t answer their questions, House chairmen say. (Photo: Michael Reynolds/EPA)

‘Stretched to the Limit’

An independent report on the terrorist attacks in Benghazi determined the State Department’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security “is being stretched to the limit as never before” and recommended construction of a consolidated training center.

The report issued December 2012 cited “grossly inadequate” security, a lack of Diplomatic Security agents, and poorly skilled local guards as factors in the attacks that killed four Americans, including Chris Stevens, the U.S. ambassador to Libya.

The report — the work of an Accountability Review Board commissioned by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and led by veteran diplomat Thomas R. Pickering — included 29 recommendations on how the State Department could enhance training methods and capabilities. The report urged Congress to “do its part” and appropriate money to do so.

With global terrorism becoming more fragmented, U.S. diplomats and security officers must be present in places where security is poor and host government support is minimal, the report said, urging: “It is imperative for the State Department to be mission-driven rather than resource-constrained.”

Protesters tear down the flag at the U.S. embassy in Cairo, Egypt, on Sept. 11, 2012. (Photo: STR-/AFP/GettyImages)

Across the State Department, 2,000 diplomatic security agents protect diplomats and U.S. outposts in 160 countries. State plans to hire 75 more agents by the end of the year, and officials want all agents to be trained for high-risk jobs.

Currently, the State Department trains diplomatic security agents at leased facilities nationwide.

The State Department spokesperson said agents take a 10-week “high-threat” training course at a military facility in West Virginia. Before Benghazi, the course lasted five weeks.

Other facilities, such as some near the Bill Scott Raceway in Summit Point, W.V., aren’t adequate, the spokesperson said. “[It’s] another reason why we need a consolidated training facility.”

‘Competing Needs’

According to a 2011 internal document reviewed by The Daily Signal, the State Department evaluated sites based on criteria such as the amount of land, proximity to State Department headquarters, and compatibility of the training center with the surrounding area.

Because the site would be operated 24/7 and produce noise ranging from explosions to aircraft operations, officials decided it should be isolated from suburban development.

Other Virginia sites considered included the Fort Lee Army base, Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, and Naval Station Norfolk. Maryland options included Fort Detrick, Fort Meade, and Andrews Air Force Base.

“We believe that the decision on where to place [the security training center] required the State Department to address three competing needs: cost, capabilities, and efficiencies,” a State Department official told The Daily Signal. “In deciding to place [it] at Fort Pickett, the State Department believes it has struck a balance among all three.”

Engineers crush rock for range improvements at Fort Pickett in 2012. (Photo: Cotton Puryear/Virginia National Guard)

Before beginning design and construction, officials must update a draft environmental impact statement and master plan to obtain necessary permits, a process that should take 10 to 12 months.

In 2009, a State Department document predicted construction would last until 2020 if it began this year.

The draft environmental impact statement, reviewed by The Daily Signal, projects that the training center will create 1,500 jobs and net revenue increases of $1.1 million in Chesterfield County $1.2 million in Nottoway County.

Even with those projected benefits, the State Department official, said, the agency hopes to cut costs.

Secretary of State John Kerry has not weighed in on the costs of the Fort Pickett plan. (Photo: Center for American Progress /Flickr)

“The State Department continues to look for opportunities to further reduce the overall cost of the project,” the official said.

Republican lawmakers, frustrated in their demands for information, can only hope so.

“The members of our committee want to make certain that diplomatic security agents and other state personnel have the right training to operate overseas in dangerous environments,” Royce and McCaul said in their May 19 letter to Obama Cabinet officials Burwell, Kerry, and Johnson. “At the same time, we have a responsibility to ensure that funds are invested wisely.”