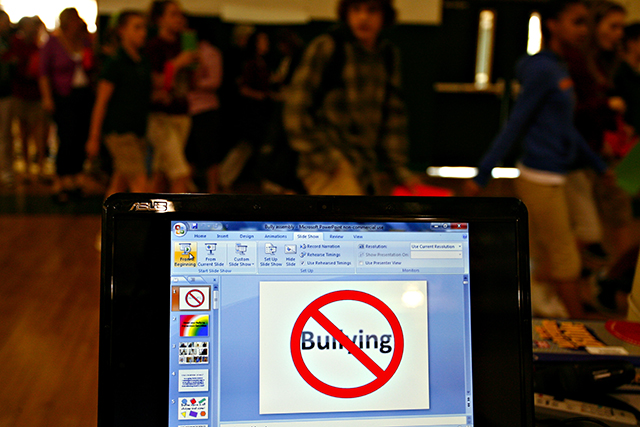

Guilty of Meanness: City Contemplates Criminal Penalties for ‘Bullies’

Evan Bernick /

Ever texted something less than civil? Something that could be considered “mean,” even?

If you do it a few times in the city of Carson, Calif., you could be found guilty of a crime.

Carson is considering an ordinance that would criminalize bullying, defined as “a willful course of conduct which involves harassment of a person(s) from kindergarten through age 25.” According to the ordinance, “harassment” includes conduct that “would cause a person to feel terrorized, frightened, intimidated, threatened, harassed or molested and which serves no legitimate purpose.” Violation of the ordinance would be a misdemeanor.

What on Earth does this mean? Like a similar anti-bullying ordinance in Vernon County, Wis., that we wrote about last year, this ordinance appears unconstitutionally vague. As the U.S. Supreme Court stated in Bouie v. City of Columbia (1964), the Constitution’s due process guarantees provide that “No one may be required at peril of life, liberty or property to speculate as to the meaning of penal statutes.” How can a young person, or anyone else, possibly predict what will cause someone to feel harassed or molested, or what will constitute a “legitimate purpose” in the eyes of police, prosecutors, judges and jurors?

To make matters worse, some examples of offending conduct in the proposed ordinance describe much of what under-25 year-olds do on a daily basis. “[C]yberbullying may include sending hurtful, rude and mean text messages; spreading rumors or lies about others by email or social networks; and creating websites, videos or social medial profiles that embarrass, humiliate or make fun of others.” So, if you “embarrass” or “make fun” of someone, you could be found to have violated the statute. If you post a series of snarky comments on someone’s Facebook wall, you do so at the risk of criminal punishment.

A moment’s reflection will yield the common-sense conclusion that giving offense can’t be grounds for limiting speech. Offensive speech is protected by the First Amendment as long as it does not fall within one of the narrowly defined exceptions the Court has carved out over the years, which include incitement to immediate unlawful conduct, obscene speech, child pornography, a threat or “fighting words”—which was defined in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) as “those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Being rude or mean doesn’t cut it.

Most reasonable people probably would agree it’s not nice to make fun of people, whether online or offline. Most reasonable people would not expect it to be illegal. Criminal law contains the harshest penalties the government can impose on its citizens. It should be reserved for extreme misbehavior. It should not be a sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of young people who can’t possibly predict if or when it will fall.