It’s Not the Value of the Chinese Currency: The Proof in Charts

William T. Wilson /

While the U.S. Treasury did not label China as a currency manipulator this week, it did criticize the Chinese authorities for recently intervening in the foreign exchange market. However, the yuan–dollar exchange value has no effect on the U.S.–Chinese bilateral trade balance.

This is because a lot has changed in the past few years.

From 1995 to 2005, China pegged its currency, holding it steady at slightly over eight yuan or renminbi against the dollar. Then, in late 2005, China allowed its currency to appreciate relative to the dollar until July 2008. After this, China heavily intervened in the market to keep the yuan weak against the U.S. dollar until about mid-2010, when it let the yuan slowly appreciate against the dollar as a crawling peg.

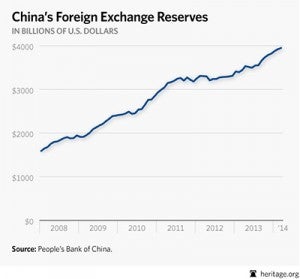

From 2008 through mid-2011, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) was only allowing small appreciations against the dollar by buying large quantities of dollars. This is easily seen in the level of China’s foreign exchange reserves. Also easily noted is that after mid-2011, the meteoric rise in foreign exchange reserves distinctly decelerates (except for the first quarter of this year). Why is that? The PBoC was not aggressively buying dollars intervening in the foreign exchange market.

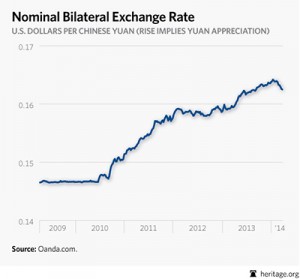

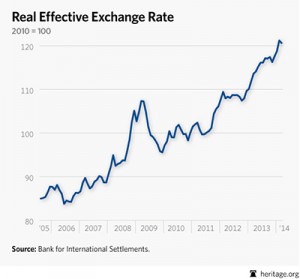

The result is that the yuan has appreciated against the dollar in both real and nominal terms: in nominal terms, by about 11 percent since mid-2010; in real terms, over the same period, by a significant 21 percent.

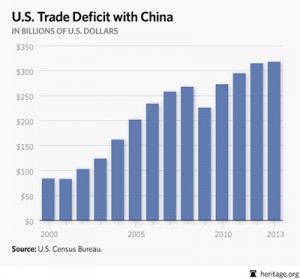

Yet the U.S. trade deficits have continued their upward trend. At $318 billion in 2013, the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China is now at an all-time high.

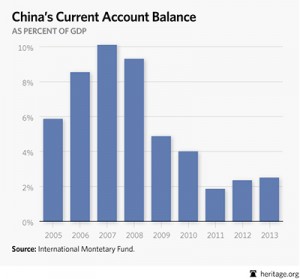

The bottom line is that China is no longer aggressively intervening in the foreign exchange market, and as Heritage economists and others have long predicted, this development is having no appreciative impact on the flow of Chinese imports to the U.S. In fact, the massive shrinkage in China’s broader current account surpluses since 2007 (a broad measure of the balance of trade with all of China’s trading partners) implies that China is actually contributing more to the economic growth of its trade partners (i.e., Chinese imports are growing faster than Chinese exports).

As Edward Lazear of the Hoover Institution points out, the dollar–yuan exchange rate did not change from 1995 to 2005, and during this period China’s exports to the U.S. increased sixfold, or at a rate of about 19.6 percent per year. Then, from 2005 to 2008, the yuan appreciated approximately 21 percent against the dollar. China’s currency was stronger and its exports in dollars were more expensive, so Chinese exports to the U.S. should have fallen. Instead, China’s exports to the U.S. continued at about the same pace, averaging 18.2 percent per year.

The only period during which exports from China to the U.S. fell to any significant extent was during the recent recession, dropping by about one-third from late 2008 to early 2010. The dollar–yuan exchange rate was unchanged this entire period.

The real manipulation is occurring through the Chinese government’s subsidies to its giant state-owned enterprises. The sooner Washington can focus on that—the real culprit—and ease away from its currency obsession, the sooner we can get to real solutions.