Crisis for Common Core: Indiana’s Uncommon Ruckus Over Education Standards

Alicia M. Cohn /

INDIANAPOLIS – What’s wrong with public education in America today? Across the country, just about everyone has an opinion. Very few, though, have the power to implement sweeping reforms.

In Indiana, a driver for the Uber car-for-hire service gets his mother on the phone for a reporter. Sharon Hurt is a 40-year veteran of the state’s South Bend public school district. What teachers need, Hurt says, is flexibility as individuals and support as a group.

“On a national level, we have to be concerned about how we’re lagging behind when it comes to other countries. Somebody’s got to take the lead on that,” Hurt says. “You can have a particular standard but it really boils down to the strength of the individual teacher and the strength of the support surrounding them.”

A “good teacher,” she adds, takes a government-prescribed education standard “and runs with it and uses it as an opportunity instead of a barrier.”

Indiana today is a battleground for one of the Obama administration’s preferred prescriptions to improve public schools — uniform national education standards formally known as Common Core State Standards.

In this special report, The Foundry examines why Common Core standards, originally touted as a bipartisan reform, proved divisive for Indiana residents — and what’s being done through layers of players to resolve the disagreement.

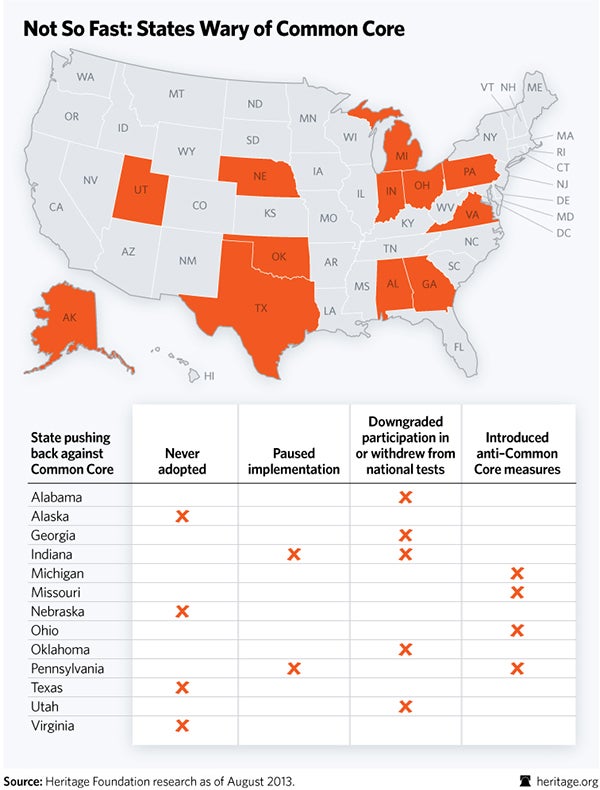

Common Core already is woven into the fabric of American education. And where the words “Common Core” appear, protests are not far behind. Common Core began as a broad reform, dreamed up by the bipartisan National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, to provide a high-quality base of academic standards that any state in the country could choose to use. In 2010, Indiana became one of the first states to adopt the standards. By June 2012, 45 states, plus the District of Columbia, also began the implementation process.

Birth of a Common Cause

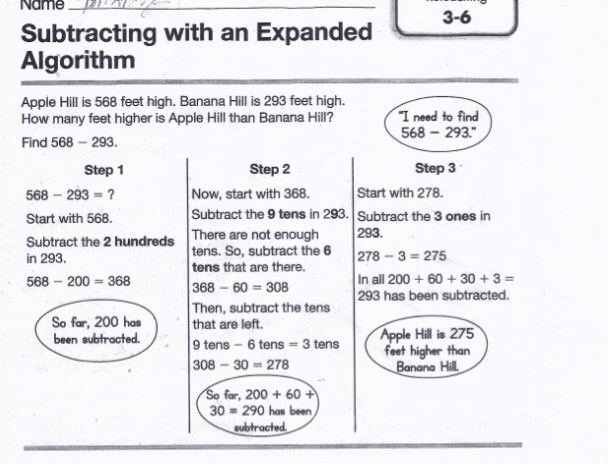

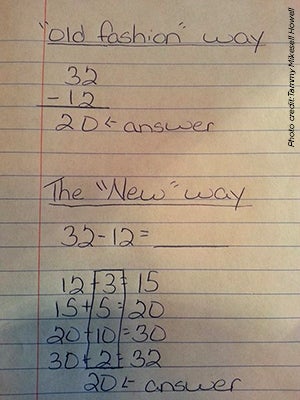

Resistance began at the individual level, with parents such as Heather Crossin, an Indianapolis mom of four. Crossin, now one of Indiana’s most vocal opponents of Common Core, asked her school’s principal why 8-year-old Lucy’s math homework suddenly focused on abstract concepts, even drawing pictures to solve problems, instead of practicing formulas.

“I assumed initially it was just a bad textbook selection. I found out that was not the case,” Crossin says. Instead, the principal brought in a representative from Pearson, the publisher, to explain the new, Common Core-aligned textbooks.

Crossin, who has appeared as a speaker at events sponsored by The Heritage Foundation, which opposes Common Core on policy grounds, recalls what happened next:

“When parents still weren’t buying what [the publisher’s representative] was selling, our principal in frustration threw up his hands and said, ‘Look, I know parents don’t like this type of math because none of us were taught this way, but we have to teach it this way because this is how it’s going to be on the new [standardized] assessment. And that was the moment when I realized control of what was being taught in my child’s classroom — in a parochial Catholic school — had not only left the building, it had left the state of Indiana. And to me, that was a frightening thought.”

Fast forward to this month, when Indiana state officials, educators and parents are struggling through a lengthy reassessment and possible replacement of Common Core. Governor Mike Pence, a Republican, last May signed into law a bill mandating the review.

The decision was a little like changing tires on a race car in the middle of a lap. The new law also set a tight deadline for the state to review and decide on education standards going forward: July 1, 2014.

As late as the last week of February, officials maintained they were “on timeline” and simply doing the work of “articulating” and “clarifying” the set of draft standards that the State Board of Education intended to vote on in April, in time for teachers to plan the upcoming school year.

By March 7, Indiana Department of Education officials conceded they would need more time, The Foundry learned, and the date to vote on new standards would edge closer to the “reassessment” law’s July 1 deadline. The state school board is expected to take up the issue tomorrow.

From the outside, Indiana’s undertaking might look easy. Prior to adopting Common Core, the state had some of the best-rated standards in the country and a system in place for revising them every six years. The latest set was implemented only in a few grades state-wide in the 2011-12 school year.

For opponents of Common Core, Indiana is a trailblazer.

“By pausing implementation, Indiana wanted to assess the cost to taxpayers and the quality of the standards – something every state that adopted the standards should have done prior to adoption,” says Lindsey M. Burke, The Heritage Foundation’s Will Skillman fellow in education. “While it’s still unclear exactly what the long-term outcome will be in Indiana, the Hoosier State provided a blueprint for other states that are interested in putting implementation on hold.”

What Prompted the ‘Pause’

When Indiana education officials released a new set of draft standards at the end of February, they were almost universally panned by interested observers and experts. Among them: University of Arkansas professor Sandra Stotsky, Hoover Institution fellow Ze’ev Wurman and Hillsdale College professor Terrence Moore.

The Fordham Institute, which is pro-Common Core, also was among the tough critics. Kathleen Porter-Magee, Fordham’s Bernard Lee Schwartz policy fellow, wrote:

“Because of Indiana’s long history of setting clear and rigorous standards for English language arts, arguably no state was better positioned to customize [Common Core] in a way that made the expectations even stronger than the Core. And yet—remarkably and inexplicably—Indiana state officials have managed to do the opposite: draft ELA [English/language arts] standards that are worse than either of the documents they hope to replace.”

So what happened? The state faces more scrutiny than is typical for a standards review, and — since Common Core is an increasingly contentious policy issue that swayed the last election of Indiana’s superintendent of public instruction – more political pressure, as well.

“Obviously, it was politics that drove the decision to review and revise standards mid-cycle, because they have a process in place for updating state standards,” Porter-Magee says. Halting implementation of Common Core to write new standards, the Fordham Institute scholar points out, disrupts not only the state’s own process but the timeline set for schools and teachers when Indiana chose to adopt Common Core.

Indiana’s last governor, Republican Mitch Daniels, was involved in the initial conversations about the benefits of a uniform set of national education standards. Tony Bennett, a Republican who was then superintendent of public instruction, helped review Common Core in draft form in 2009. Daniels and Bennett pushed for adoption early on, although the state had just finished its latest scheduled revision of existing standards, generating new math standards that got high grades but ultimately weren’t used.

Daniels, now president of Purdue University, declined to comment for this report. Bennett, who lost re-election in 2012 despite heavily outspending his Democratic opponent, could not be reached for comment.

In his first term as governor, Pence — a former congressman and Republican presidential prospect — could well reverse the policy of his predecessor by dropping Common Core. Pence touted the “timeout on national education standards” in his 2014 State of the State speech in January, calling for “uncommonly high” standards in Indiana. “They will be written by Hoosiers, for Hoosiers and will be among the best in the nation,” he promised.

Parents Feel Shut Out of Decisions

To opponents of Common Core, this second overhaul in Indiana is reason for cautious celebration.

“Looking at where we’ve been and where we are now is pretty amazing,” says State Senator Scott Schneider, a Republican who saw legislation to pause implementation and re-evaluate the Common Core standards fail twice before H.B. 1427 passed last year. “We started the ball rolling with adopting new standards in the state of Indiana. That’s a positive.”

No matter what happens, Common Core likely will linger in Indiana through its influence over the standards-writing process — including the pool of standards used by the evaluation panel to create their draft.

“We have said very clearly we are looking for the strongest, clearest, most appropriate standards, and the origin [of them] has not necessarily been something we’re willing to shy away from,” says Danielle Shockey, Indiana’s deputy superintendent of public instruction. “If the strongest language in a standard for computation happens to have come from the origin of Common Core, then that’s certainly something we want to talk about as we move forward.”

Common Core opponents suspect a bias toward it already was embedded in the review process. With Iowa, Florida, and Arizona renaming their own state standards to avoid the tainted Common Core branding, critics have reason to suspect Indiana might end up doing the same thing.

Standards-based education in America only began in the 1980s. Yet to many, setting the standards has become a murky, bureaucratic process, and one that leaves the most interested parties on the outside.

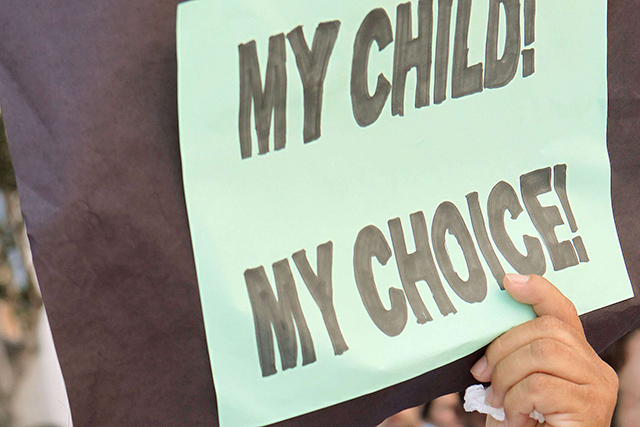

Many of those who feel excluded are parents. They were among the more than 100 state residents who traveled to public hearings to comment on the draft standards before the Indiana State Board of Education during the last week of February.

Jill Olecki spoke from the podium with a 1-year-old baby strapped to her back and her three other children coloring just outside a room in the State Library in Indianapolis. “Why make our kids the guinea pigs?” Olecki asked board members, who silently took notes at the front of the room.

In the back, another mom handed out buttons she had designed — “Say No to the Common Core,” they read — and many speakers proudly wore them as they approached the podium.

One consistent theme: The troubling perception that state officials hadn’t listened enough in the past, and suspicion that they still weren’t.

“[The hearing] was intended very directly to address the feedback and concerns that parents had expressed, and others had expressed, that there hadn’t been enough dialogue and engagement with the public about what were we doing moving toward Common Core and what were the implications for schools around the state,” says Claire Fiddian-Green, the governor’s special assistant for education innovation.

Reservations and Good Intentions

Last Wednesday, state school board member Andrea Neal met with Pence to tell the governor about her own concerns about the draft standards — which she calls “obviously bad” and “not only inferior to Indiana’s pre-Common Core standards but worse than the Common Core itself.”

“I felt that the governor was not fully aware that this was not just about who writes them,” Neal says of the meeting with Pence. “I think by the time I left he did have a full understanding [that] anti-Common Core people aren’t just saying no to everything; they do have a standards litmus test.”

Pence’s education aide, Fiddian-Green, describes him as determined to get it right. “The direction from the governor all along,” she says, “has been to fulfill not only the letter but the spirit of [H.B.] 1427 and conduct a comprehensive, transparent evaluation of the standards and to make sure that whatever we come out with are adopted by Hoosiers for Hoosiers and have a very high bar, that they’re actually very rigorous college and career-ready standards.”

Of course, that was the original intent behind Common Core, as well. Fiddian-Green explains:

“I think those who were at the table at the time would tell you that it was very much a state-led effort that then led to other states saying, ‘We agree, this makes sense to have a national set of rigorous standards, that reflect the fact that we’re in an increasingly mobile and global society. So that if you go to school in Massachusetts, then you move to Indiana, then you move to California, you can be reassured as a parent or as a business deciding to relocate your business somewhere that you’re going to have the same consistent set of standards being taught in classrooms.”

Many states also see that sharing similar standards produces resource benefits, including shaping the textbook market and standardized texts.

“Having common standards allows for common tests, which might allow for reducing costs to states,” says Jaryn Emhof, national director of communications at the Florida-based Foundation for Excellence in Education. “Florida’s been doing assessments for a long time and so has a plan and a robust and a budgeted place to do that every year. Not every state has those in place.”

In many other states, Emhof says, the Common Core standards are better than their current ones. However, Indiana’s previous standards for both math and English/language arts were rated higher than Common Core by the Fordham Institute. (The Common Core authors dispute the grades their standards received.)

College Board President David Coleman, one of Common Core’s lead writers, targeted the issues of remediation and accountability when he pitched the standards in August 2010 to Indiana’s Education Roundtable, an advisory body to the State Board of Education co-chaired by the governor (Daniels at the time) and superintendent (then Bennett). The roundtable recommended adoption of the Common Core standards. That same month, the school board — composed of the elected superintendent and 10 members appointed by the governor — voted unanimously to do so.

Indiana also signed onto one of the Common Core-aligned (and federally funded) national testing consortia: Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, better known as PARCC. By federal law, every state assesses schools and student progress through standardized testing; some states develop those tests internally, but PARCC would provide common tests to multiple states. The state has since pulled out of that, as well.

Obama Administration Dangles Incentives

“Indiana was very interested in becoming maybe a little bit more competitive as a state,” Molly Chamberlin, chief assessment and accountability officer for the Pence administration’s Center for Education and Career Innovation, says of the 2010 decision. Although the state was highly ranked for its education standards, leaders saw room for improvement on factors such as percentage of adults with bachelor’s degrees, students who need remedial courses before college, per capita income, and SAT scores.

And in Washington, D.C., the Obama administration provided another important incentive by offering waivers that would free states from the mandates of the previous administration’s No Child Left Behind law. Obama education officials conditioned those waivers in part on whether a state adopted common standards and assessments.

To Crossin and other parents, that represents another alarming layer of bureaucracy and government control. Crossin says she was already wary of the distance between her problem in her child’s classroom and decision-makers in the State House.

Burke, Heritage’s education reform expert, is among those who agree:

“With the myriad federal fingerprints on the effort, there’s no doubt that the effort will grow Washington intervention into education. For any state interested in retaining its educational decision-making authority, only a complete exit from the national standards and testing push will ensure they can do so down the road.”

Proponents of Common Core argue the project began as a state-led attempt to work together to improve education overall. The federal government signed on later.

“There’s a lot of things that are federally incentivized from time to time and states have to make that decision: Is this good for our state?” Emhof says. “So they retain the control over — just like we’re seeing in Florida, just like we’re seeing in Indiana — making tweaks and changes in the implementation.”

Some Hoosiers, though, felt left out of the decision to implement the new standards.

“I really think out of 150 legislators in the building, there were probably no more than a handful that had ever heard of Common Core, yet we adopted them as standards in the state of Indiana,” recalls Schneider, the state senator.

In fact, a poll conducted last May and released in August by PDK/Gallup found that 62 percent of Americans had never heard of the Common Core standards, even though by that time all but five states had started implementation. Around that time, some states “paused” implementation or pulled out of the testing consortia. Much of the pushback began when individual parents started asking questions, although it has been helped along by media-savvy advocates of limited government such as commentator Glenn Beck.

‘Importance of What We’re Fighting For’

Angela Davidson Weinzinger founded the Facebook group Parents and Educators Against Common Core Standards in early 2013 and saw membership jump to thousands by that summer. She was taken by surprise by the Common Core standards in California, where she is a school board member in the Travis Unified District.

“When people first join the [Facebook] group, it’s usually because they’ve noticed the homework coming home with their kids,” Weinzinger says. She encourages new members to read information shared on the Facebook page, then contact their local representatives. “Common Core can’t be fought on a national level at this point. It has to be done in your states,” she tells people.

In Indiana, Crossin and another mother, Erin Tuttle, already had co-founded the grassroots group Hoosiers Against Common Core. They reached out to “natural allies,” including tea party and pro-family groups such as Indiana Family Institute and Eagle Forum.

The issue generated activists ready to react at a moment’s notice. One of them is Jackie Rhoton, the mom passing out “Say No To the Common Core” buttons. And although stories are written in Washington, D.C., about its demise, the tea party movement is alive and supporting the fight against what it sees as government overreach into local and state education decisions.

Rhoton says Common Core “has been one of the top three [priorities] for the past two years for the Indiana Tea Party,” ever since Crossin and Tuttle brought it to the movement’s attention. She is part of a self-organized “Common Core subcommittee” composed of six Indiana tea partiers who closely monitor anything to do with Common Core and report back to a coalition of in-state tea party groups.

“None of us are funded; it’s all purely the issue that has caused this,” Crossin says. “The fact that we’ve gotten as far as we have in spite of the fact that those we oppose have incredibly deep pockets — I mean, K-12 education is a five- to 600-billion-dollar industry, there’s a lot of people that stand to make a lot of money; Bill Gates has pumped I think $200 million into [Common Core] — …in my opinion [that fact] speaks volumes about the importance of what it is we’re fighting for.”

But even as efforts now seem to be driven by conservative grassroots, the debate is not delineated by party lines. Besides Republicans such as Daniels and Bennett, for example, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush (founder of the Foundation for Excellence in Education) is a proponent of Common Core. Bush last October called Common Core a strong solution to “the hodgepodge of dumbed-down state standards that have created group mediocrity in our schools.”

Opponents’ concerns range from government intervention into education — Burke’s “chief concern,” as well as the critique of New York University professor Diane Ravitch, who likes “voluntary national standards” but believes federal involvement disqualifies Common Core — to purely content-based criticism. Some say Common Core doesn’t emphasize phonics in English/language arts or standard algorithms for math, for example. The debate over the content of the education standards themselves likely will rage indefinitely.

“I think we’ve done a fair job [in Indiana] of separating ourselves from the governance issue, trying to drive sort of a roadblock, a wall, between the federal government and setting standards,” Schneider says. When it comes to achieving high-quality standards, though, neither the state senator nor anybody who called for them is declaring success yet.

“We knew all along that there was always going to be a risk that Common Core could continue to be adopted, under a different name, or a percentage, and I think that lies at the feet of the governor because the governor appoints all the members of the state [school] board and by virtue of that, it is a governor’s directive,” says Schneider, whose Senate district is north of Indianapolis.

The Meaning of ‘Rigorous’ Standards

Fiddian-Green, the governor’s education aide, says the Pence administration doesn’t see the current process as a radical shift in the state’s education policies.

But who decides the definition of “rigorous”?“I think the whole idea behind Common Core was that we needed to increase rigor across the entire country, irrespective of what might or might have been the case of standards in Indiana,” she says. “And I think this is an extension in that it represents the governor’s belief, and the legislature’s, that we need to make sure that they are the best standards for Indiana and that Indiana educators and business folks believe that these are indeed the more rigorous standards.”

Crossin and school board member Neal are pushing for content experts such as Stotsky (English/language arts) and Stanford University’s James Milgram (math) to sign off on any standards Indiana eventually uses. Stotsky and Milgram refused to endorse Common Core in the past. The Pence administration reached out to both as part of a three-week public review process, asking them to review the draft standards.

Stotsky, who helped develop the state’s English/language arts standards in the 2000s and published some of her analysis of Common Core through Heritage, calls the new standards a “cut-and-paste” job that appears to simply reproduce “the discredited Common Core standards.” She declined to submit a full review.

“There is no point in my spending my valuable time critiquing a set of ELA [English/language arts] standards after March 14 that may be worse than or no better than Common Core’s ELA standards, or that may even be identical to them,” Stotsky wrote to Fiddian-Green.

Neal says she emphasized Stotsky’s importance in her meeting last week with Pence, extracting a promise that the governor would call the expert personally if necessary to secure her help.

But such opinions may have little influence on the process.

“Input from experts is very, very valuable, but I also think that an expert’s opinion is still an opinion, and so I think it’s going to be very, very important for us to be weighing the comments of everyone who’s weighing in,” Chamberlin says.

Rounding Up the Experts

Chamberlin points out that some of the criticism about Common Core’s introduction to Indiana two years ago came from people “not feeling like they’re getting an opportunity to have their voices heard” in favor of other experts who pushed Common Core.

“I don’t want to indicate that opinions of experts won’t guide the process; they absolutely will,” Chamberlin adds. “[But] one person’s opinion weighing 90 percent over everybody else’s, that’s not really the way that the evaluation panel’s going to work.”

Chamberlin and Fiddian-Green emphasize that review panels are made up of experts drawn from every part of the state — urban, suburban and rural — and all aspects of education, with an emphasis on subject matter.

More than 200 educators spanning K-12 to higher education were involved, along with parents and representatives from major state-based and multinational businesses such as Toyota and Eli Lilly and Co. Staff of Indiana’s school board and education agencies selected members of panels based on recommendations from principals and superintendents, school board members, the Education Roundtable and state workforce development officials.

Behind the scenes, Sujie Shin, assistant director of the Center on Standards and Assessment Implementation at WestEd, helped the school board assemble a pool of standards and reviewed the redrafting process. Opponents have criticized the connection because WestEd, a nonprofit that does research and consulting on education, is funded in part by a contract with the U.S. Department of Education and helped many states implement Common Core last year. Shin was not available to comment.

For math, the panel looked at four sets of standards, including Indiana’s two previous sets and those from Common Core and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). For English/language arts, the panel looked at the previous Indiana standards and standards from Common Core and the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE).

The various standards weren’t labeled during the evaluation, Chamberlin says, as it was meant to be a blind review. Neal and others argue that the pool of options diminishes the end result. (NCTM and NCTE standards, much like Common Core, aren’t universally admired.) Additional sets of standards — including options Neal pushed for, standards written by Stotsky and highly rated ones used in Massachusetts — were available to any evaluator who desired other options.

“They’re evaluating sets of standards that really have already been vetted by large groups of folks, so it’s not like they were coming in saying, ‘We’re going to do this all our own way.’ It’s kind of taking years and years of expertise that’s been built up,” Chamberlin says. “People act like these [Common Core standards] came out of the blue. … Actually they borrowed from a lot of work that had already been done.”

The new law required the state to conduct a fiscal impact study looking at four scenarios, ranging from continued use of Common Core to writing completely new standards. One of the most important findings was the potential negative fiscal impact of delaying until July 1 to adopt standards.

The school board was scheduled to vote on new standards April 9, but the major players admit the vote may have to be delayed by at least a month — and Fiddian-Green admits the possibility of two. At the board’s monthly meeting tomorrow, members likely will likely discuss and make that decision, spokeswoman Lou Ann Baker says.

Teachers Struggle to Prepare for Class

Dennis Van Roekel, a former math teacher in Arizona who is president of the nation’s largest teachers union, the National Education Association, made headlines last month with a letter to NEA members describing Common Core implementation as “completely botched” in many states. He called for greater participation by teachers to make a “course correction.” Those pushing for significant revision of the draft standards want to delay until closer to July 1, but caught in the middle are the teachers of Indiana.

“We have three weeks planned this summer of curriculum work. What are we going to be working on?” asks Diane Lee Scott, director of curriculum and instruction for Indiana’s Lebanon school district, who also spoke at the Indianapolis hearing. Scott adds:

“Indiana made a determination that we were adopting Common Core State Standards, and starting with the 2010 school year we began implementing the timeline that they laid out for us to help with the transition. And part of that transition was for the incoming kindergarten students to exclusively have their curriculum focused around the Common Core for [English /language arts] and math and then going into first and second [grades] so by the time they were in third, which was the projected date for the new state assessment, those students would have had the opportunity to learn and show their mastery.”

Passage of the pause-and-evaluate legislation forced teachers to teach from hybrid standards, Scott explains, since school districts remain accountable for preparing students to succeed in upcoming state assessments.

“Even that is not determined yet: what that state assessment is going to be, because you can’t do that until you know what your state standards are,” Scott adds. “It’s like we have this moving target. … We’re humans, we’re not factors that you can just flip a switch. There are people trying to do the work. I don’t know that that is always recognized or understood.”

If Indiana’s new standards vary by more than 15 percent from Common Core, the state will have to commission assessments aligned with them. Based on the draft standards, Pence aide Fiddian-Green says that seems the most likely scenario. That could mean another 12 to 18 months to select a vendor and to create and field test questions, with a goal of readiness for the 2015-16 school year.

Before the school board can vote on the draft standards, the evaluation team will meet again to reconcile feedback after the public comment period closes Wednesday (March 12). As of last Friday, 850 online comments had been submitted. The state’s Education Roundtable and the College and Career Ready panel also have to review the draft.

What Happens Next

The College and Career Ready panel is a key component because the Obama administration requires that any state’s standards meet the definition of “college and career ready” to earn a waiver from some No Child Left Behind requirements. In practice, that means that if Indiana’s new standards are more than 15 percent different from Common Core, they require a stamp of approval from another state-convened team of experts.

Heritage’s Burke is among informed onlookers who believe that requirement is a big part of the administration’s attempt to incentivize the use of Common Core.

“While preparing students for success in the workplace or to enter college is important, the Obama administration has used the ‘college and career readiness’ language as a euphemism for Common Core national standards and tests,” Burke says.

Dawn Wooten, a professor at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne and a member of Indiana’s career-ready panel, says she will look for specific content in the standards. Among them: critical-thinking exercises, “obvious scaffolding of writing and reading skills from one grade to another,” and whether grade standards are appropriate to students’ cognitive abilities.

The career-ready panel hasn’t been involved so far in the writing process, although some members were on initial evaluation teams. If the panel doesn’t sign off on the new draft, it will require yet more revisions. Its review likely will be the third or fourth week of March, Wooten says.

If everything else about setting new education standards is uncertain in Indiana, all involved appear to agree on one thing: If the current process fails to generate acceptable standards by July 1, there is no Plan B.

This story was produced by Foundry staff writer Alicia Cohn. Follow her on Twitter: @aliciacohn. Nothing here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation.