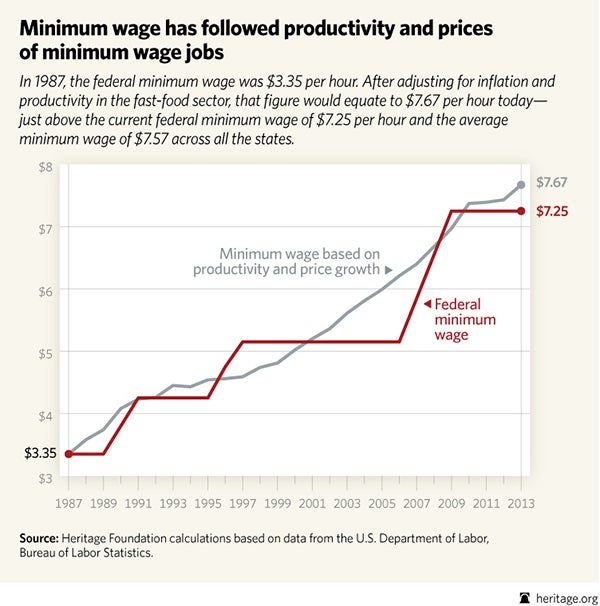

Minimum Wage Has Followed the Productivity And Prices of Minimum Wage Jobs

Rachel Greszler /

Proponents of increasing the minimum wage have argued that the current minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is drastically lower than it should be and that the minimum wage has not kept pace with inflation and productivity growth. Some have claimed that the minimum wage would be $17 today, or even $22, if workers were fully compensated for increases in inflation and productivity.

However, those measures consider productivity and prices across the entire economy. Prices and productivity growth vary significantly across sectors, and productivity growth in the service sector—which houses many minimum-wage jobs—has historically been very low. In the fast-food industry, for example, productivity growth over the past quarter century (1988–2012) was roughly one-sixth that of the larger economy.

Despite claims that the minimum wage should be significantly higher, an examination of the data shows that the minimum wage has in fact quite closely tracked the productivity growth and output prices of jobs that are usually filled by minimum-wage workers. After adjusting for productivity and price growth within the fast-food industry, the minimum wage of $3.35 in 1987 would be about $7.67 in 2013. While this is slightly higher than the current federal minimum wage of $7.25, it is on par with the average minimum wage across the states of $7.57 in 2013.

Given the low productivity growth in most minimum-wage jobs, those wages cannot rise as fast as the broader economy. Attempting to artificially increase such wages would force employers to reduce jobs and increase prices. As a Heritage analysis shows, raising the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour by 2016 would lead to 217,000 fewer jobs per year and $30 billion lower gross domestic product per year.

There are better alternatives to increasing incomes and opportunities in the U.S., and they don’t have to do with bigger government.