7 Ugly Truths About the House Farm Bill

Daren Bakst /

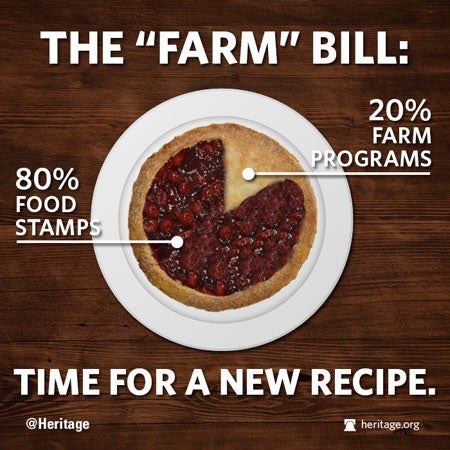

The recently defeated House farm bill was fundamentally flawed. The House can now fix these flaws by going back to the drawing board and developing real reforms. To adopt necessary reforms, the House needs to separate food stamps from the farm programs and consider each on its own merit in two distinct bills.

Splitting the bill is not the end of the process, though—it’s just the start of the process.

As the House moves forward, it helps to look back at just some of the ugly truths about the House farm bill:

- Costly. The House would have spent more than President Obama and the Senate on the costliest farm program: crop insurance. In fact, Obama would have cut costs by close to $12 billion, while the House would have added about $9 billion.

- Anti-reform. The House bill would have done nothing to address the skyrocketing costs of crop insurance, such as placing a cap on the amount of subsidies that farmers can receive or developing a means test. In fact, the House rejected an amendment that would have made such common-sense reforms.

- Pro-Christmas tree tax. The House bill that was considered on the floor would have lifted a stay that blocked the United States Department of Agriculture from taxing Christmas tree producers and importers. When the full House had a chance to reject this tax by keeping the stay, it overwhelmingly supported the Christmas tree tax. It also would have done nothing to repeal the other comparable 19 check-off taxes that exist in law.

- Pro-corporate welfare. One of the most egregious “farm” programs is the Market Access Program. Taxpayers are forced to subsidize the overseas marketing of wealthy companies. The House overwhelmingly rejected an amendment that would have eliminated this program. If this wasn’t bad enough, the House also overwhelmingly rejected an amendment that would have eliminated a program that promotes farmers markets.

- Guaranteed payments. The House bill would have set up a “reference price program,” which was sold as covering only major losses for farmers. In fact, the program was even more generous than the Senate program and would have effectively guaranteed payments to some farmers as soon the bill became law.

- Provided extreme protection for farmers. The House bill would have pushed what is called a shallow loss program, helping to guarantee most revenue for farmers. The concept of a safety net for farmers who suffer significant losses would have been trumped by a new model of protecting farmers from virtually all risk. Even the American Farm Bureau Federation in a 2011 letter expressed concern about shallow loss programs: “A shallow loss program is a drastic departure from any previous farm policy design. Federal farm programs have traditionally existed to help farmers survive large, systemic losses. Shallow losses, however, can arise from a variety of systemic or individual sources and do not typically jeopardize the survival of a farm operation.”

- Anti-consumer. The bill would have maintained the sugar and dairy programs that restrict supplies in order to drive up both sugar and dairy prices. Sugar prices have consistently been two to three times higher than world prices. The Government Accountability Office analyzed the dairy program and found that between 1998 and 2004, U.S. butter prices were more than double international prices and that U.S. cheese prices were up to 58 percent higher than international prices.

The farm bill should move away from subsidies and toward free-market policies. Without government intervention, farmers and ranchers can be freed up to best use their land and make decisions based on their needs, not on government edict.