The Magical Thinking Behind the U.N. Arms Trade Treaty

Ted Bromund /

When the U.N. Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) opened for signature on June 3, 67 nations signed immediately. The U.S. was not among them, but U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry announced that the U.S. would sign “as soon as the process of conforming the official translations is completed satisfactorily,” which will take until late August.

The fact that the world is eagerly signing a treaty that is not yet available in all the U.N.’s official languages says a lot about the magical thinking behind it. It doesn’t matter what the treaty says: What matters to many treaty advocates is how the treaty makes them feel. Britain’s deputy foreign minister summed up the treaty’s magic with his claim that, “The force behind so many states wanting to conclude an arms trade treaty after so long meant something. The world is now different.”

No, it isn’t. Words on a piece of paper are meaningless until they are implemented. If the nations of the world wanted to have higher national standards on their import and export of arms, they could have had them without a treaty. As the U.N. itself acknowledged when the treaty negotiation process began, what the world’s nations wanted above all wasn’t higher standards: It was a treaty that acknowledged as inherent their national right to buy, sell, manufacture, and transfer arms. And that is what they got.

The problem with the world’s arms trade is not, as treaty defenders like Oxfam America President Raymond Offenheiser like to claim, that there are “loopholes in the current, irresponsible global arms trade.” The problem is that some nations deliberately sell arms to terrorists and dictators, and many others are corrupt. If a nation cannot maintain democratic law and order, it will not be able to implement the ATT. A treaty cannot make the incompetent competent. Nor can it make the malicious responsible.

Treaty advocates usually criticize the U.N. Security Council for employing a “body bag approach,” and decry the failure of Security Council arms embargoes. But the Security Council has the authority of the U.N. Charter and the ultimate sanction of Chapter Seven enforcement—war, in plain English—behind it. The ATT has none of this. If the Security Council has failed, as the treaty advocates correctly acknowledge, there is no reason to believe the ATT will work any better.

The world does not need a treaty on the arms trade: The world needs better governance and more democracies—without them, no treaty can work. With them, no treaty would be necessary. Improving governance and building democracy are indeed long processes. But the alternative to admitting honestly that they are what we need is to fall victim to the magical thinking that has driven the entire ATT process. A treaty, after all, will not stop Iran from arming the Assad regime.

The vitriol with which the treaty supporters attack their critics testifies to their underlying faith that they have found a magical solution to the world’s ills. Offenheiser offers a classic example of this with his condemnation of Senator Jerry Moran (R–KS) and Representative Mike Kelly’s (R–PA) concurrent resolution against the ATT, which he links with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) as multilateral success stories.

The CTBT has never been ratified by the Senate. The U.S. is currently not in compliance with the CWC, and the CWC is, as Heritage has long noted, a classic unenforceable treaty. In any event, with North Korea busily testing nuclear devices, Iran pressing ahead with its nuclear program, and Syria gassing its own people, this is perhaps not quite the right moment to be praising the CTBT and the CWC as successes to be emulated.

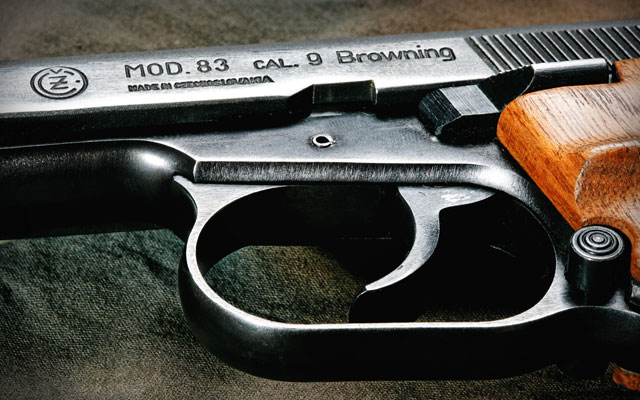

What drives much of the opposition to the ATT, of course, are concerns about its possible domestic effects. Treaty defenders deny that any such effects exist, but curiously, it was the same defenders who fought vigorously—and successfully—to ensure that the treaty would not explicitly exclude lawfully owned civilian firearms.

Thus, when Amnesty International, which began the push for the ATT, states that the treaty is only a “start” on the road to the control of “domestic internal gun sales,” concerns about domestic effects are a reasonable response. The impression left by treaty advocates is not that they support the right to keep and bear arms: It is that they recognize that criticizing this right is bad politics, but are occasionally unable to restrain themselves.

The upcoming U.S. signature on the ATT will have serious legal consequences. But if the opposition led by Senator Moran and Representative Kelly is any evidence, the treaty will spend years, or eternity, in the in-box of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It will do just as much good there as it will do for the people of Syria: none at all.