Why Federal Transit Hasn’t Lived Up to Its Promises

Emily Goff /

Next City, the nonprofit organization that produced this recent Super Bowl commercial parody, and other transit advocates claim that trains, buses, and even trolleys provide practical ways for people to travel between home and work, and places like church and the store. They say transit is affordable and helps the environment by eliminating the need for cars. The facts show otherwise.

As Heritage Foundation visiting fellow Wendell Cox reports, the federal transit program has failed to deliver on its promised objectives, despite having received generous federal gas tax subsidies for the past three decades. Namely, it has been unable to:

- Relieve traffic congestion. Traffic congestion has worsened in all major metropolitan areas, shown by a 125 percent increase in peak period travel times. Transit has not convinced Americans to abandon their cars. Since 1970, 58 million more people have chosen to get to work by car each day, while the number of transit commuters has increased by only 250,000. Transit has actually suffered a travel market share loss in urban areas.

- Provide mobility to jobs for low-income citizens. Low-income workers in metropolitan areas—those earning less than $15,000 per year—use cars at nearly the same rate as their more affluent yet equally rational neighbors. Transit does not give them a practical transportation alternative.

- Reduce air pollution. Transit has not reduced the volume of traffic, nor is it likely to convince enough drivers to make the switch to transit going forward. Thus, Cox explains, transit can claim only a 0.3 percent reduction in CO2 emissions from cars. Such a small “gain” carries an enormous price tag: $4,000 per ton of pollution reduced.

Supporters chalk up transit’s substantial costs to necessary “investments.” Yet Cox points out that between 1983 and 2010 “each 1 percent increase in ridership has been associated with a 9 percent increase in expenditures.” Highways and roads have been shortchanged in the process, because billions of federal gas tax dollars, originally intended to fund expansions and maintenance of the nation’s roads and bridges, were instead diverted to transit. In 2010 alone (the most recent data available), transit received $6 billion, or 17 percent of federal gas taxes—a disproportionate share, given that transit accounts for a mere 1 percent of the nation’s surface travel.

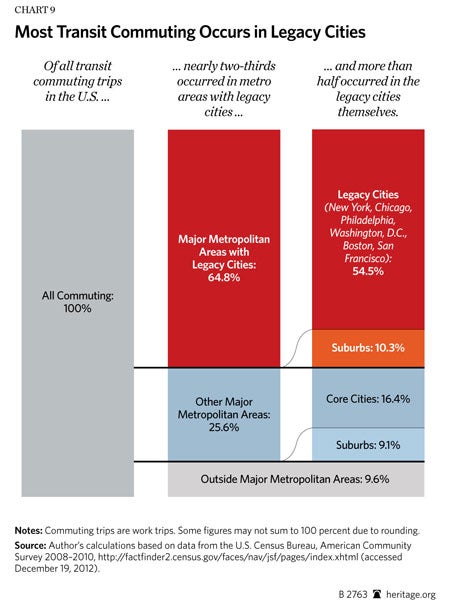

Transit is not a national program, because its use is highly concentrated in just six “transit legacy cities,” driven by dense downtown areas called central business districts. These districts have the best paying jobs, and commuters to these areas have higher salaries. Of these commuters who do use transit, many have no other option, because they do not own cars.

Motorists and truckers pay the federal gas taxes that fund transportation. Because of the sizable diversion of this money to transit, funding for roads and bridges has been stretched razor thin—a reality that states are currently grappling with. Because of transit’s poor performance and concentrated use in a few cities, it should not be a federal spending priority.

Congress should phase out the federal transit program and its subsidy over a five-year period. During this time, states and localities can decide what transit services they want to provide and identify potential cost-saving measures to implement.