Evangelical Christians Carried Trump to Victory. What Nonbelievers Assume About Them Is Often Wrong.

Carrie Sheffield /

There’s no doubt that President-elect Donald Trump’s victories at the polls are fueled by a stalwart base of support from evangelical Christians.

But what many non-Trump voters don’t realize is that American evangelicals don’t fit the stereotypes projected or assumed by many non-evangelicals. Sadly, this causes mistrust, and even disdain, that isn’t warranted and contributes to the polarized division in America.

Religion is a major cultural divide exacerbating Left and Right polarization.

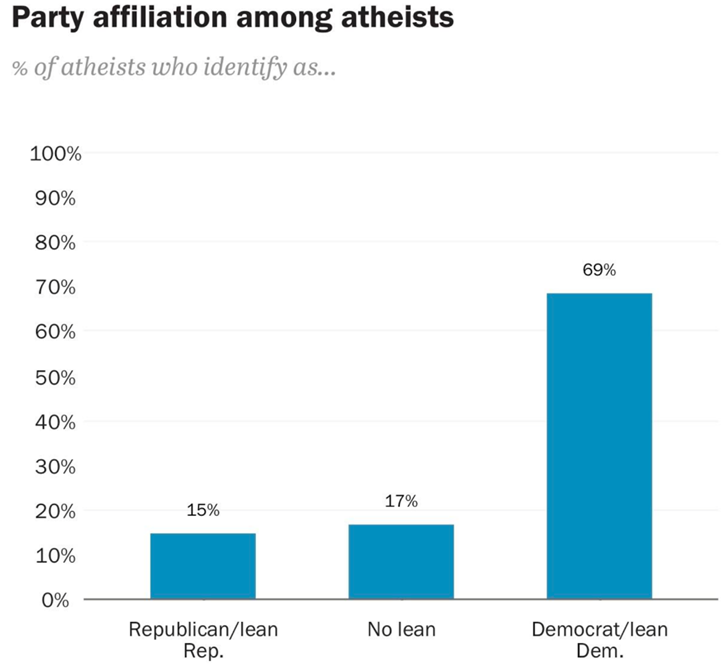

A whopping 69% of atheists said they identify as Democrats, but only 15% identify as Republicans and 17% as independents, according to Pew Research Center.

Pew also found that atheists are disproportionately white, which could help explain the growing cultural divide between more educated white Democrats and more socially conservative, working-class, nonwhite voters.

Many Americans are blinded by “perception gaps”—disparities between what non-evangelicals imagine evangelicals believe and what evangelicals actually believe. These gaps are uncovered in recent survey research by More In Common, a nonprofit funded by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

“These perception gaps constrain our ability to envision a future where America’s faithful play a central role in helping us navigate division and foster social cohesion,” the authors write.

More In Common partnered with the polling company YouGov, rated in the top 1% of hundreds of pollsters by FiveThirtyEight’s polling gurus for methodological quality and transparency, to survey over 6,000 Americans. The nonprofit’s findings swat down what it describes as “myths” about people of faith.

The first myth is that among religious Americans, “faith is driven by politics”—e.g., that politics underpins our Christian worldview.

But only 4% of evangelicals consider their political party their “most important identity.” Shockingly, non-evangelicals wrongly think this proportion of evangelicals is 40%—a “perception gap” of 36 percentage points.

This gap creates what researchers call “collateral contempt,” or “the tendency for animosity toward political opponents to spill over to religious groups that are perceived to be aligned with one political team.” This partisan animosity isn’t only uncivil, it’s also detached from reality.

Just 46% of evangelical Christians said they identify as Republicans; 22% said they identify as Democrats, 26% as independents.

White evangelicals make up a powerful and large—but shrinking—portion of the electorate, from 26% in 2016 to 21% today, according to Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Olsen noted recently in The Wall Street Journal that Trump’s popular vote victory came as the former and future president expanded his appeal among non-Christians and nonbelievers.

“Most telling was Mr. Trump’s increased support among those who don’t adhere to Abrahamic faiths,” Olsen wrote. “His support rose with voters who told pollsters they were ‘something else,’ from 35% to 38%, and with those who professed no religious belief, [from] 25% to 29%. These voters combined are 30% of the electorate, more numerous than either self-described Catholics or Protestants, up from 22% in 2016.”

American secularism is on the rise, although the social media platform X recently buzzed with news that first-time Bible buyers broke new records. However, the data from More in Common dispels the myth that “faith is becoming irrelevant,” finding that a whopping 73% of all Americans—not just evangelicals—say faith is key to their identity.

More in Common reports that “the number of Gen Z Americans who say that their faith identity is important to them is only 9% below that of baby boomers.” That gap could shrink, though, as more young men in Gen Z are hitting the pews.

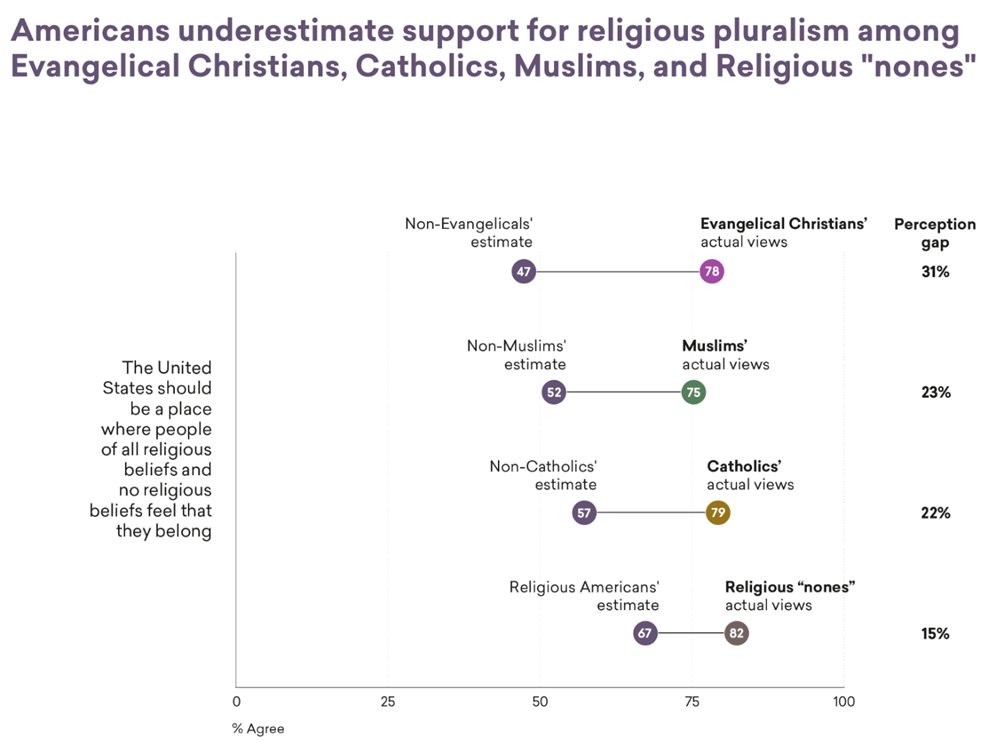

More in Common’s last debunked myth is that “religious people are intolerant.” Perhaps because many believers feel misunderstood, researchers found that Americans of all faiths overwhelmingly embrace pluralism and reject discrimination—either against those of other religions or nonbelievers.

Non-evangelical Christians assume that only 47% of evangelicals value religious pluralism, but 78% of evangelicals say they do.

Interestingly, the nonreligious are far more likely to overestimate the intolerance of religious people than the reverse. Religious Americans estimate that 67% of nonbelievers embrace pluralism, while 82% of the nonreligious say they support pluralism—a perception gap of 15 percentage points against non-believers vs. a gap of 31 points against evangelicals.

As a Trump-voting evangelical, I wasn’t surprised by findings from New York University professor Jonathan Haidt that conservatives are better versed in liberal worldviews than the reverse. This research tracks with my personal experience.

In my recent memoir “Motorhome Prophecies,” I share my faith journey away from agnostic disbelief in God and my eventual baptism into Protestant Christianity seven years ago this month.

I spent nearly 12 years as an agnostic, much of that time avoiding and assuming the worst of religious people. I did this in part because I’d been harmed by a zealous father who abused my seven biological siblings and me in a homespun, heretical offshoot Mormon cult.

During the process that led to my Protestant conversion, I studied principles of metaphysics and, contrary to stereotypes, found a robust community of Christians who embrace scientific inquiry.

One example: a ministry called Science + God created by former Harvard physics professor Michael Guillen, a nondenominational Christian and former atheist. Guillen earned a Ph.D. in mathematics, astronomy, and physics from Cornell before teaching physics at Harvard and serving as ABC News’ chief science correspondent.

Evangelical Christians are a diverse bunch, and perhaps befriending one might shatter your preconceptions. Leaving election season and entering Christmastime, our nation heals by moving toward empathy, curiosity, and tolerance among people of all creeds.

We publish a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Daily Signal.