A Nuclear Waste Carol

Jack Spencer / Katie Tubb /

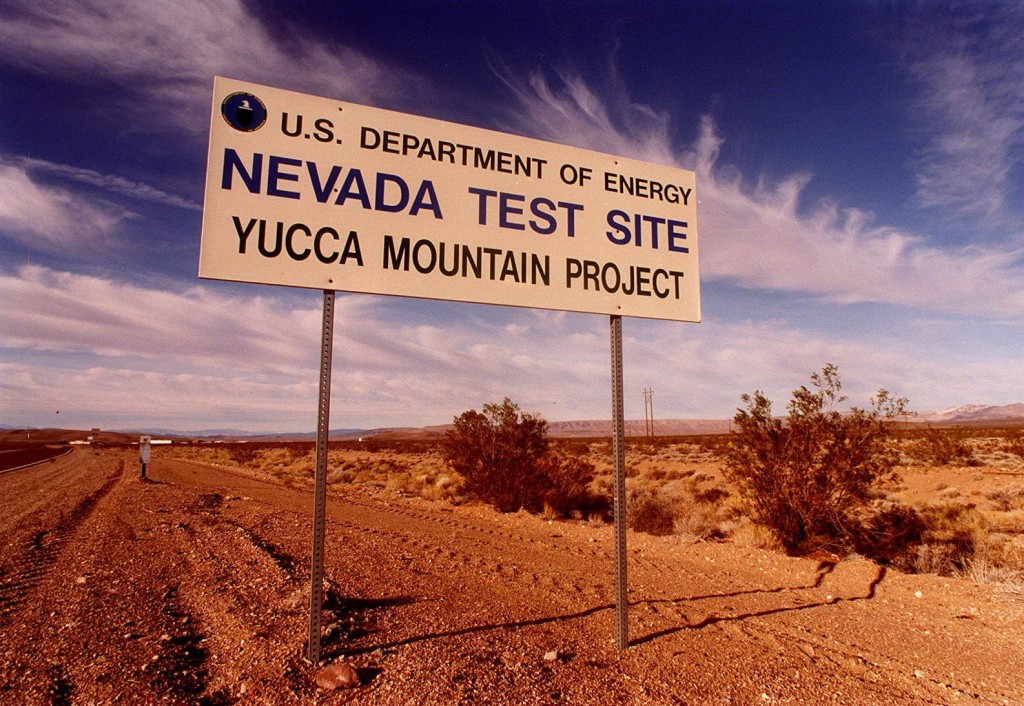

Yucca Mountain was dead—to begin with. There was no doubt whatsoever about that. The register of its burial was signed by the Senator, the Chairman, the Secretary, and the President.

Now three Senators, maybe four, were left to pick up the pieces.

On one bitterly cold Christmas Eve, these Senators gathered round a fire to discuss the nation’s predicament. Imbibing Christmas cheer, the soaring rhetoric meandered from interim storage to nuclear waste finance and new government entities. But each topic was met with a “bah humbug” from the others.

The debate went on for hours—well past midnight. Enthusiastic oratory tapered first to a murmur and then to silence as each Senator fell asleep where he sat, heads cricked sideways in contented slumber.

But suddenly, the Senators were awoken by a strange presence in the chamber.

Startled, but staid, the Senators had just gained their composure when an apparition, badly beaten and torn, appeared: There before them stood the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Past.

Carrying a faded copy of the 1982 Nuclear Waste Policy Act, as amended, the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Past told the sad story of the Nuclear Waste Policy Act:

In life it took the responsibility of managing nuclear waste and gave it to the federal government. It created a fee for industry to pay the cost of nuclear waste-related activities. And finally, the Act set a date, January 1998, for the federal government to begin making good on its promise to collect waste.

In theory, a splendid plan. But in practice, the Act was a massive failure.

The federal government collected approximately $35 billion—but no waste. After spending $15 billion on Yucca Mountain, where the Act said it must go, the President attempted to end the project while tons of waste lay stranded at nuclear power plants, operators left with no recourse but to sue the government for its broken promise.

As the Ghost faded away, he left the Senators with a single message: “You cannot delay any longer. Look at home and abroad for the answer to your quandary!”

No sooner had he left when someone else appeared: The jolly Ghost of Nuclear Waste Present.

Full of ideas and excitement for new opportunity, the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Present displayed a globe to show the Senators the key to fixing nuclear waste policy. With a whiz of the finger, the globe took off in a furious spin. He stopped the globe instantly by placing his finger on France. France had a fine system for managing nuclear waste, he explained. They reprocessed the spent fuel to reclaim useful elements and store what was left safely underground.

He spun the globe again and stopped on Sweden. “There they are building a repository much like what the U.S. planned in Yucca Mountain, and they are doing it with local support,” he exclaimed. “They are going down a similar path next door, in Finland.”

One more spin left the Ghost’s finger placed squarely on the United States. The Senators thought surely there must be some mistake—after all, it was precisely the failure of U.S. nuclear waste policy that brought them there at that moment. But the Ghost merrily assured them he was not mistaken. His finger was on New Mexico, home of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), the world’s only fully functioning underground nuclear waste repository, where the U.S. disposes of defense nuclear waste.

“Think, dear Senators, the waste producer in each successful program is responsible for nuclear waste management. That is the key to any successful nuclear waste program,” the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Present cried out as he faded away into the wintry night.

“You mean it doesn’t have a single-purpose government entity responsible?” one perplexed Senator said to the others. Another asked, “Taking the Nuclear Waste Fund off budget won’t fix our woes?” And before the next Senator could finish a thought about consensus-based processes for finding a repository, the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Future stood before them in terrifying foreboding.

“Come with me,” the Ghost demanded. “I will show you what the future of nuclear energy could be if you continue in your shortsighted ways.”

The Ghost of Nuclear Waste Future led them to a misty graveyard. “Why have you brought us here?” one quivering Senator pleaded. The Ghost of Nuclear Waste Future said nothing, but motioned toward a headstone. The promise of nuclear energy was dead.

Two government officials sniveled off through the misty graveyard, their coffers nicely padded from the Nuclear Waste Fund that did not take a speck of spent fuel away, leaving the growth of the nuclear industry choked from behind.

And there before the Senators stood the grave of one Tiny Tim, whose house had become colder and the pockets of his parents emptier from higher electricity bills.

The Ghost of Nuclear Waste Future left them standing, cold, staring at the grave of Tiny Tim. Stupefied, they tore their eyes from such an awful fate and looked up, only to find themselves back in their overstuffed armchairs, the fire cold, the room dark.

“This cannot be,” cried a Senator, leaping up to stoke the fire. Their discussion began in earnest to heed the warnings of the Ghosts and mend the wrongs of the past.

The Nuclear Policy Act of 2013, they declared, must remove the responsibility of waste management from the federal government. They must put Nevada in control of Yucca Mountain to negotiate directly with the nuclear industry, maximize the financial potential of the facility for themselves, and share in the responsibilities of regulatory oversight.

“But why stop there?” one Senator asked. “Why not remove Washington from the picture—we can’t rightly say we’re experts in the field. Why not unleash American ingenuity? There are so many options for storing spent fuel, as the Ghost of Nuclear Waste Present showed us. Why not give utility companies some options for waste management services based on what they find economical, while making good on our promise by ensuring that there is always an option for them in Yucca?”

“By Jove, what an idea!” another Senator replied. “Why, once the industry is responsible for their own waste, utilities will also have the incentive to find new ways to produce less of it, too. More nuclear power but less waste!”

It was all so simple. Each of the Senators realized that they didn’t have to have all of the answers. They just needed to free the industry to provide them. As the Christmas morning sun came up, the Senators eagerly set about to work.

In fact, the Senators were better than their word. They did it all, and infinitely more; and for Tiny Tim, who did not die, they celebrated. They became as good and wise a team of legislators as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.

They had no further interaction with the Ghosts, but lived upon the free market principle, ever afterwards. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, “Merry Christmas, Every One!”