Somaliland: Proof That Democracy in the Horn of Africa Is Possible

Morgan Lorraine Roach /

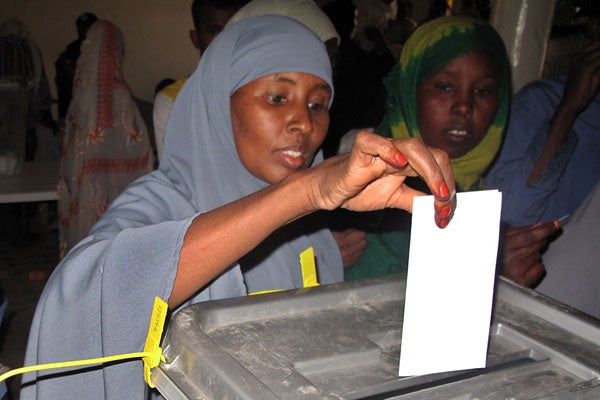

Today, citizens of Somaliland head to the polls to elect their local municipal council representatives.

While the dysfunctional Somalia gets most of the attention in the Horn of Africa, its northern neighbor Somaliland has stood out as a success story.

This election is the fifth direct vote in Somaliland since 2002, but is the first election of local councilors, a move that the International Republican Institute (IRI) says coincides with the central government’s initiative to decentralize government.

The election will also determine the government’s three major political parties. According to law, only three political parties are allowed to govern, as this lessens the prospect of the population dividing itself according to clan and/or region affiliation. Somaliland’s three dominating political parties are the UDUB, UCID, and KULMIYE. However, they will have to compete with UMADDA, DALSAN, RAYS, WADANI, and XAQSOOR. While the UCID and the KULMIYE are favorites, the UDUB will not be participating. In September, the UDUB accused the National Election Commission of partisan bias and withdrew its candidacy.

The election is not without its pitfalls. As IRI notes, there will be no voter roll, increasing the chances of voter fraud. Somalilanders will also vote for candidates on an open-list system rather than a political party. This raises practical challenges, as the ballots will list all of the candidates by name, number, and (as has traditionally been used) a symbol for Somaliland’s largely illiterate population.

The U.K.-based charity Progressio notes that in Hargeisa District alone, there could be up to 225 candidates on the ballot. Furthermore, in the counting process, if a ballot is rendered void (e.g., two candidates are selected for the same position), the vote will still count—but for the candidate’s political party.

The law stipulates that the victorious parties must garner at least 20 percent of the vote. As this is unlikely to happen (because there are seven parties competing), a ranking system will be used. The results of the percentages that the parties have gained in each region will be given ranking numbers, and the three winners will be selected through the ranking system of the votes cast in the six regions based on proportional results.

Neither Somaliland’s election system nor the government as a whole is perfect. But 10 years after its first referendum, the government has proven itself effective, and more importantly, Somalilanders approve overwhelmingly of the democracy they helped put together. According to IRI’s June 2012 public opinion survey, 86 percent of people think Somaliland is headed in the right direction, and 80 percent of respondents stated that they considered Somaliland a “full democracy” or a “democracy, but with minor problems.”

Somaliland’s access to the governing process via free and fair elections has unified its diverse communities in a way that numerous governments in Mogadishu have failed to achieve. Moving forward, Somalia’s new leaders have a lot to learn from their northern neighbor.