Is Big Labor Reducing Worker Wages, Opportunities for Growth?

Rachel Greszler /

The Harris-Walz campaign used Labor Day to advocate for the power of Big Labor, thanking the “organizers, activists, workers, and leaders of the labor movement who have helped build this nation.”

But the Biden-Harris administration’s embrace of Big Labor—as in big national labor organizations, as opposed to small, local unions—actually hasn’t helped workers as unionized workers’ wages have fallen behind the wages of nonunion workers over the past four years.

Unlike small local unions that are in better positions to represent the unique needs of their members and that may even have productive relationships with management, the Big Labor movement is increasingly putting politics, power, and one-size-fits-all policies above the personal well-being of many workers.

As nationwide Big Labor organizations are expanding their reach by representing workers across entirely different occupations and industries, they’re becoming increasingly disconnected from the everyday workplace concerns of the individual workers they are supposed to represent, and the consequences are evident in workers’ choices and paychecks.

Despite the Biden-Harris administration asserting itself as the most pro-union administration ever, and employing a “whole of government” approach to increasing unionization across the U.S., the unionization rate is at an all-time low of 10% (just 6% among private-sector workers).

In states that don’t force workers to join a union as a condition of employment, only 5.7% of workers are unionized.

That’s down from a high of roughly 35% of workers who were unionized in the 1950s.

So, why has unionization plummeted? Simply put, unions are providing less and less of the things that workers want, and more of the things they don’t want.

For starters, many workers don’t like unions spending their dues on politics, instead of representation, and some don’t want to be forced to be represented by a union that they believe hates them.

Most workers also don’t like adversarial work environments, but pitting workers against employers—including dehumanizing tactics like unions’ iconic use of 12-foot blowup rats to depict management—is Big Labor’s bread and butter.

Workers and employers are in business with one another—not in competition against one another. When unions instill hostile work environments and break the direct line of communication between workers and management, that hurts both their bottom lines.

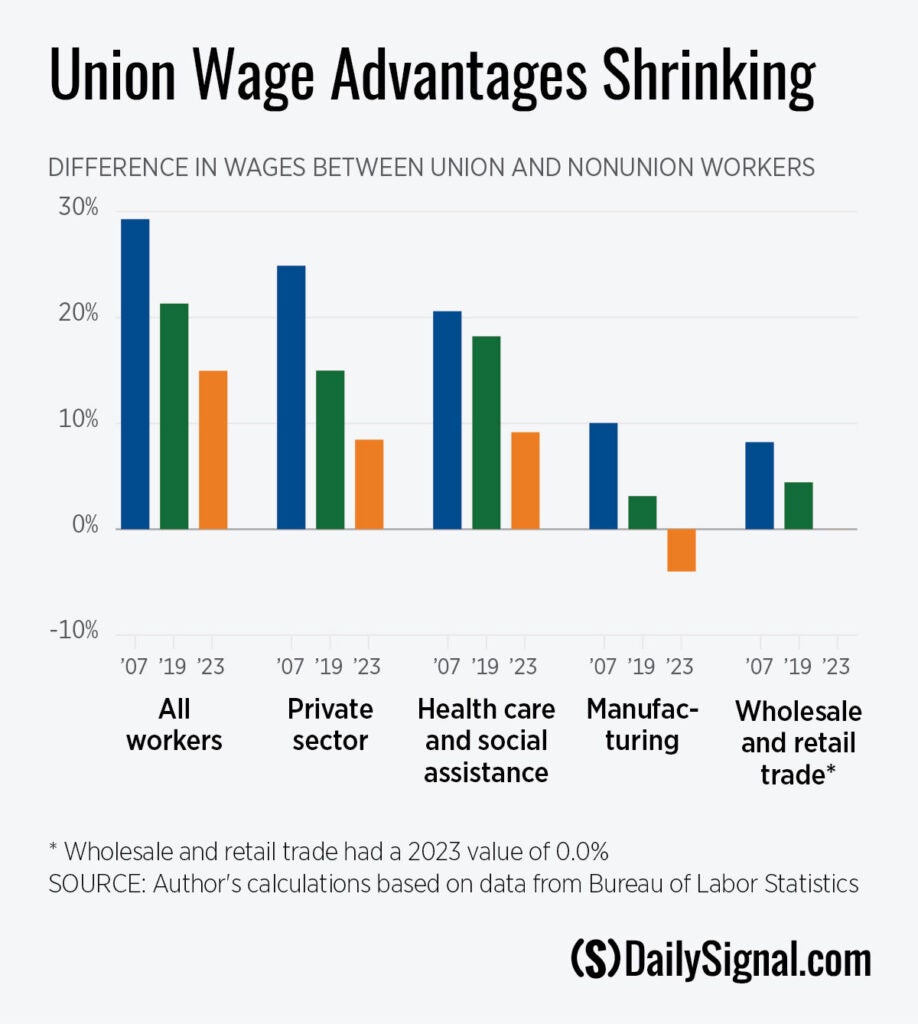

Moreover, Big Labor’s emphasis on politics and power instead of focusing on the individual workers it represents hasn’t paid off for workers’ wages. Over the past four years, union wage growth was 6.4 percentage points lower than nonunion wage gains (15.8% nominal growth for union workers versus 22.2% growth for nonunion workers).

Subsequently, unions’ wage advantage fell from 21.3% in 2019 to 15.8% in 2023. In health care and social services, unions’ wage advantage fell by half, from 18.2% to 9.2%. In the wholesale and retail trade, it disappeared, from 4.4% to 0.0%.

And in manufacturing, it reversed; union jobs now pay 4% less than nonunion jobs. These stats don’t factor in union dues that usually take 1% or more from workers’ paychecks.

Union workers’ lagging wages aren’t the failure of Big Labor to go to bat for higher pay, because Big Labor is admittedly quite good at that. Rather, it’s because Big Labor strikes out things like innovation and investments that make workers more productive, and which are crucial to sustained wage gains.

Looking toward 2025 and beyond, workers cannot count on the strong jobs market to continue, and a slew of the Biden-Harris administration’s labor regulations will make it harder to find the jobs and rising incomes Americans want and need. Those regulations include new prohibitions on apprenticeships, new restrictions on independent workers, and new impediments to flexible hours and upward mobility.

The keys to greater worker prosperity and personal satisfaction are expanding opportunities for workers to gain the education and experience that lead to higher wages, and reducing government barriers that limit the jobs and occupations workers can pursue and that reduce workers’ paychecks.