The New GOP Litmus Test on School Choice

Jay Greene / Jason Bedrick /

Party platforms are a way of signaling to voters the policies that politicians are likely to pursue if they’re elected to office. But platforms also send a message to a party’s candidates about what policy positions the party expects them to support.

If elected officials go against their own party’s platform, they might expect to be challenged in a primary.

That’s why the fact that the new Republican Party platform endorses universal school choice is such an important development.

For the first time, the Republican Party is signaling to voters and its own politicians that they should pursue policies that enable all families to choose the educational options that align with their values and work best for their own children—whether public or private, religious or secular.

“We believe schools should educate, not indoctrinate,” said Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis on Tuesday on the second night of the 2024 Republican National Convention. “We stand for parents’ rights, including universal school choice.”

That’s a dramatic departure from the platforms the Republicans adopted in 2016 and 2020, which only mentioned school choice in passing and did not fully embrace making choice available to all families.

Before now, Republican politicians could say they were adhering to their party’s platform if they were only willing to support school choice policies that were limited to specific populations, like families with low-incomes, students with special needs, or those enrolled in failing public schools.

Now, the bar has been raised.

If Republican officeholders and candidates want to abide by their party’s platform, they will have to support universal school choice policies for which all families would be eligible.

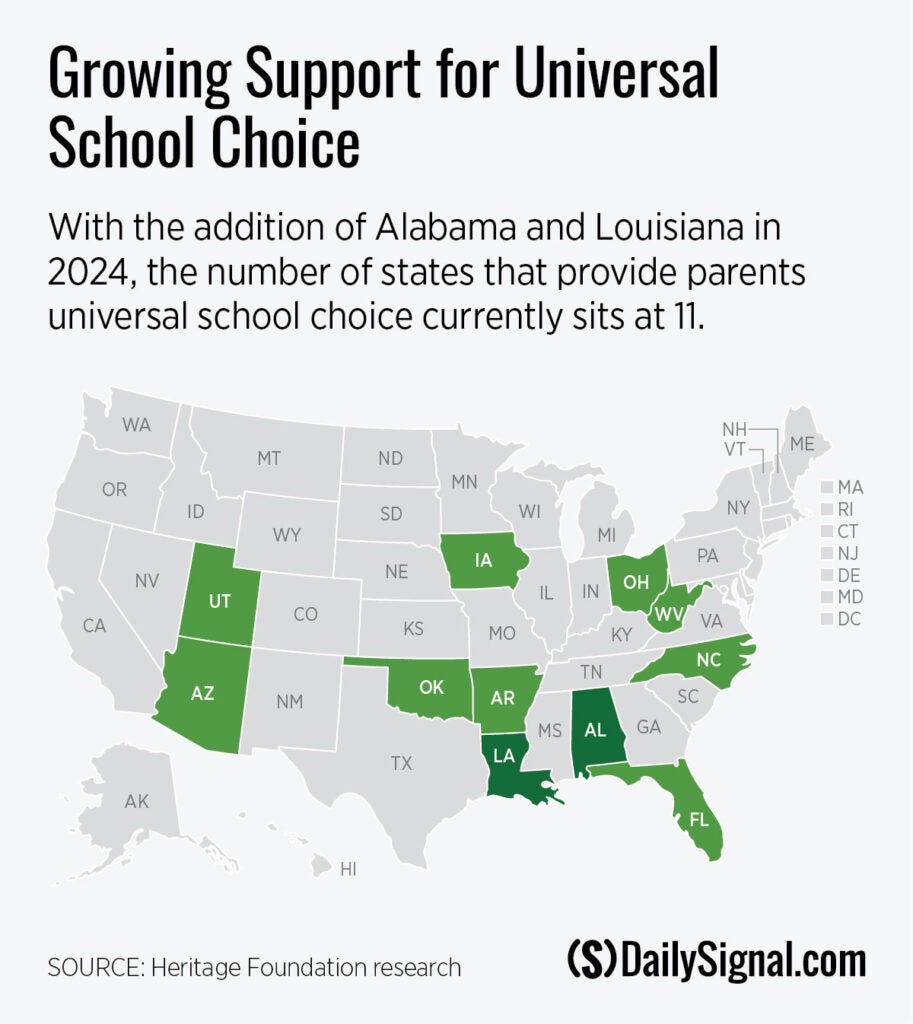

There has been a wave of adoption of those universal school choice programs over the past four years, with 11 states embracing that approach. All 11 of those states have Republicans in control of both legislative chambers and the governor (except North Carolina, where the Democratic governor allowed it to become law without his signature).

In some states, such as Iowa, school choice advocacy groups funded primary challenges that replaced Republican legislators who had previously opposed choice bills with others who backed the policy.

This enforcement of party discipline helped ensure that Republican legislative majorities translated into school choice victories.

In other states with Republican majorities, legislators have split over whether they favor passing universal programs or more limited, targeted school choice policies.

Unable to get agreement among Republicans on the right approach has delayed adoption of any school choice bills in some states, such as Texas and Idaho.

The adoption of a national Republican Party platform that fully endorses universal school choice may end that delay by pushing more Republican legislators wishing to adhere to their party’s platform to switch to the universal camp.

Those who don’t get on board may face primary challenges, even if they support limited choice programs. Backing universal school choice is becoming the new standard for Republican state policymakers.

Of course, sometimes elected officials stray from their party’s platform without consequences. But when parties signal that an issue is a top priority, party discipline to the national platform tends to become the norm.

We saw that with respect to the abortion issue. For a number of years, there were pro-life Democrats and pro-abortion Republicans. But the issue became salient enough that both parties enforced discipline and either drove those who dissented out of office or people switched their positions.

The same process appears to be underway on the issue of school choice. Democrats who have been supportive of school choice, even with more limited policies such as charter schools or means-tested vouchers, are being forced to change their positions or face defeat in primaries. The opposite is occurring among Republicans, who are facing pressure to support universal programs or lose to opponents who do in the primaries.

In the short term, this sharper divide between the parties will make adoption of limited school choice harder in states controlled by Democrats. But in states where Republicans control both legislative chambers and the governor, adoption of universal school choice policies may get easier.

There are currently 23 states fully controlled by Republicans compared to 17 fully controlled by Democrats, with the other 10 states with split control.

Given that only 10 of those 23 Republican-controlled states have universal school choice, we might expect to see more than a doubling in the number of universal school choice states over the next several years as party discipline on this issue begins to be enforced.

If so, more than half of K–12 students nationwide would be eligible for school choice, up from about 36% eligible today.

The universal school choice wave has just gotten started and shows no signs of slowing down.