China’s Maritime Gamble: A Departure From Gray-Zone Coercion in East Asia

Brent Sadler / Ruben Frivold /

Surges in military aggression near Taiwan since President Lai Ching-te’s inauguration last month are defining a provocative new Chinese military posture. At the same time, violent skirmishes with the Philippines are breaking out in the South China Sea, around Second Thomas Shoal. Beijing’s new commitment to escalation is a marked departure from its signature gray-zone activities, which now raises unprecedented issues for Washington.

Namely, how does Beijing’s new behavior in these two spaces fit into its broader strategic ambitions? And, more importantly, what happens next?

The most recent Chinese military demonstration followed the inaugural speech by Taiwan’s newly elected president on May 20. Lai has been vilified in Beijing and, as such, China didn’t miss the opportunity to express dissatisfaction with a show of force.

For a few days, China’s military presence in the Taiwan Strait remained relatively normal. That changed on May 24, when China began a series of military drills surrounding Taiwan called Joint Sword-2024A.

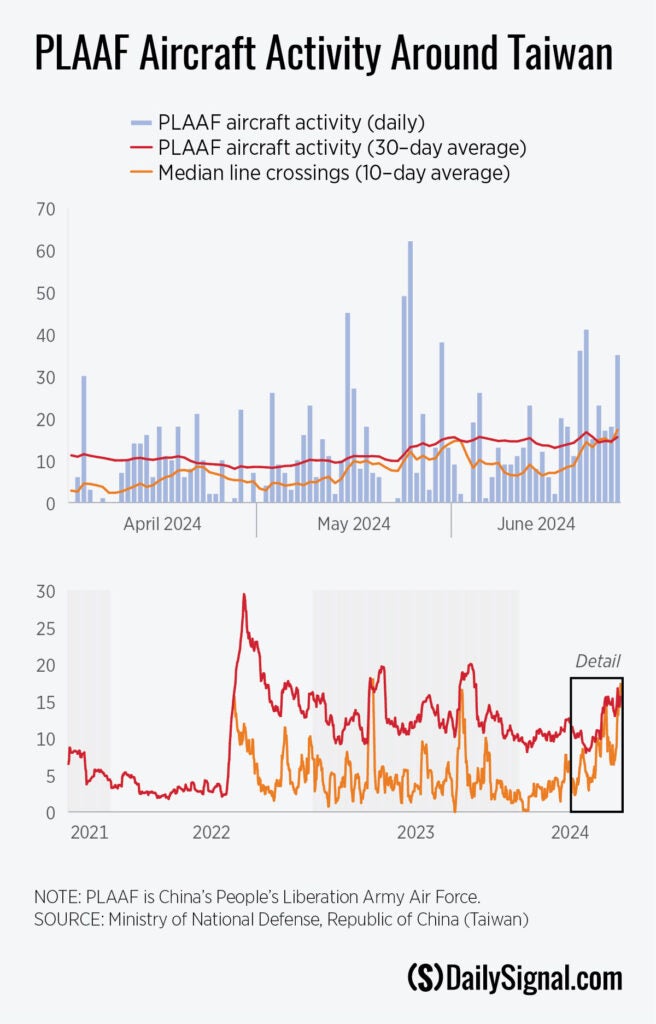

The drills produced this year’s highest recorded activity of People’s Liberation Army Air Force aircraft near Taiwan. Of the 62 aircraft detected, 47 crossed the median line in the Taiwan Strait—an even more provocative action.

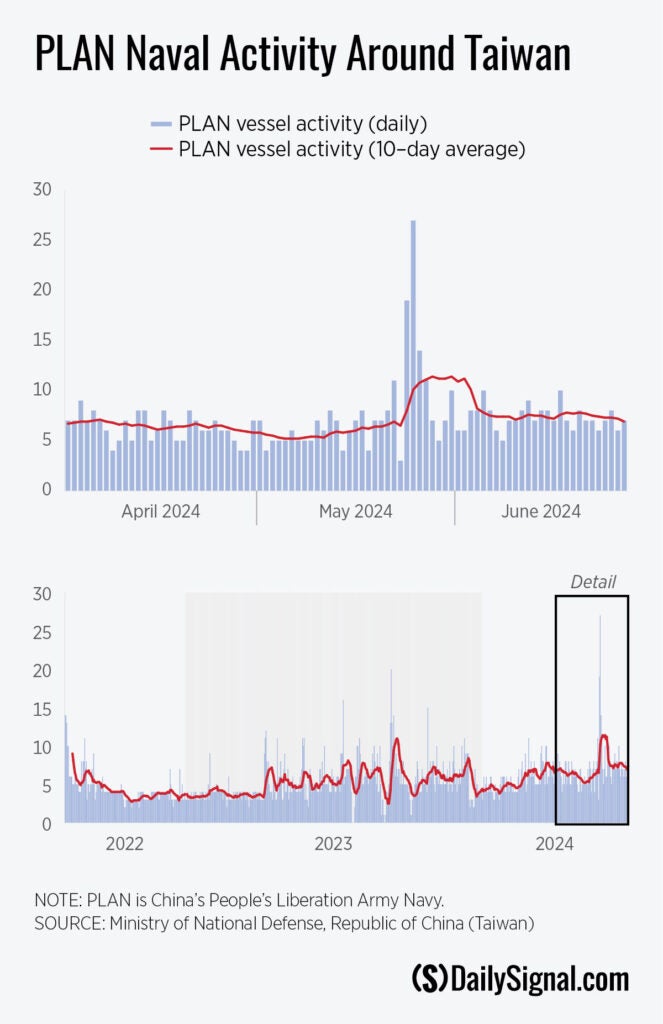

China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy activity also peaked on May 25, with 27 ships active around Taiwan. That’s the highest single-day PLAN activity since recordkeeping began in November 2020—even exceeding the naval response to then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan trip in 2022. It also represented an almost 400% increase over the 30-day average.

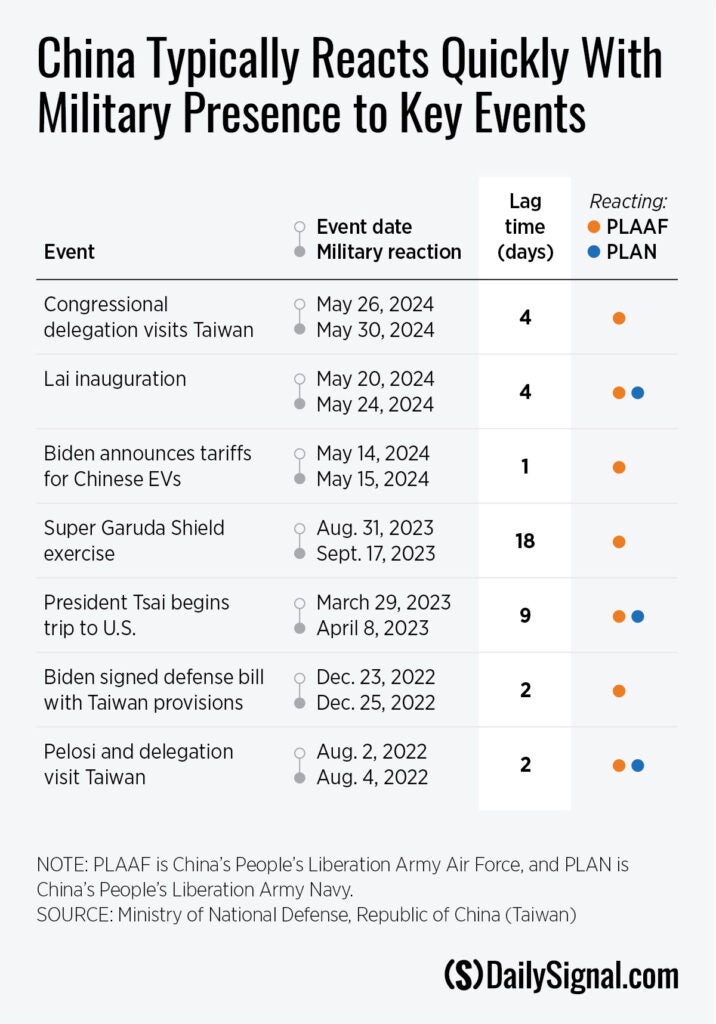

Furthermore, the three-day delay before Joint Sword began was instructive. Looking at past events triggering a military reaction from Beijing, a pattern emerges. Even when Beijing is caught off-guard, as it seems it was with Lai’s speech, it can respond and sustain an elevated military presence around Taiwan within several days.

By May 25, Chinese military activity began winding down, only to spike again in response to a U.S. delegation to Taiwan on May 26 led by the House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas.

The visit shouldn’t have been a surprise to Beijing, but it took about four days to see the expected Chinese military reaction. On May 30, the PLAAF dispatched 38 aircraft around Taiwan, with 28 crossing the median line.

Between June 21 and 27, another surge in activity was witnessed. The highest day saw 41 Chinese aircraft active around Taiwan, with 31 crossing the strait’s median line. That corresponded to a 10-day average of more than 17 median-line crossings, a figure not seen since August 2022.

The surge seemingly coincided with clashes at Second Thomas Shoal, but also aligns with increased military training and exercises typically seen in the summer.

Additionally, in a stark departure from the past, PLAAF aircraft have crossed the median line almost 70% of the days this year. The consistency has helped normalize this aggressive posture. Before September 2020, the PLA had only crossed the median line of the Taiwan Strait four times since the demarcation was established in 1954.

Now, each military escalation is perceived as less threatening since the baseline of what is considered ‘normal activity’ has gradually changed—a mindset that complicates predictive and timely action. When military escalations are normalized, one’s threat calculus also adjusts, but it does so to the advantage of the aggressor, giving less time for the defender to react.

This troubling trend is broader and involves more than aircraft and warships. On June 18, a Chinese nuclear-armed submarine surfaced in the Taiwan Strait, a possible Jin-class ballistic missile submarine based on Hainan Island. That was only the fourth time a submarine was spotted in the strait since 2019.

Moreover, China Coast Guard officials illegally boarded a Taiwanese tourist boat in an act of intimidation near Taiwan’s Kinmen Island—another departure from past behavior this year. Prior to that, China always maintained respect for Taiwan’s control of the waters around Kinmen. It follows the introduction of a 2021 CCG law that authorizes deadly force and a new regulation allowing foreigners to be apprehended in China’s declared waters.

This leads us to consider developments in the South China Sea—another area that is becoming increasingly central to China’s regional priorities.

After decades of concerted efforts, the South China Sea is increasingly resembling a Chinese lake. In the past decade, the PLA has developed several artificial islands that sustain naval and paramilitary presence at numerous contested features far from China.

That has occurred despite assurances in 2015 by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to then-President Barack Obama that China had “no intention to militarize” the artificial islands. Those artificial islands have since sustained the increasingly provocative use of PLAN, CCG, and maritime militia in the South China Sea.

Beijing has also strategically imposed fishing bans to reportedly better leverage its repurposed fishing fleets as a maritime militia. All of this has resulted in the increasing frequency of confrontations, injuries, and damage to other nations’ maritime forces.

That’s unsustainable, as escalations can quickly unfold into more serious conflicts. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. of the Philippines has already warned that if a Filipino is killed, it will be understood as an act of war: “Almost certainly, it’s going to be a redline.”

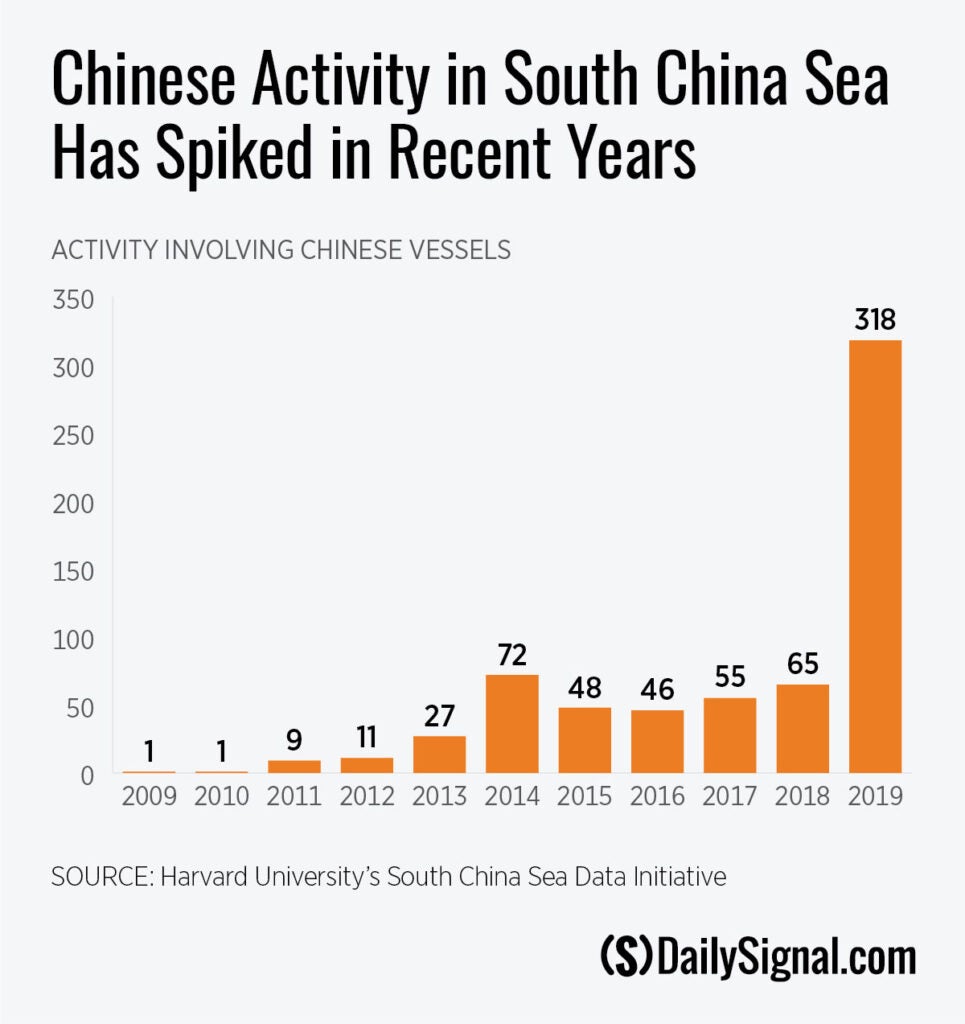

Insights gained from analyzing data sets from the South China Sea Data Initiative provide a helpful perspective into the general trend of China’s South China Sea activities. For example, the 2015 monthly average of reported instances of Chinese maritime activity in the South China Sea stood at about four. In 2019, the monthly average was about 26, including the strategically important Luzon Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines.

This snapshot provides a clear, data-driven rebuttal to Xi’s assurances to Obama.

While open-source data further documenting this trend is lacking, China’s most recent escalation serves as an example of an even larger trend. On June 19, unprecedented hostility unfolded around Second Thomas Shoal, a now familiar hot spot. This time, Chinese coast guard vessels engaged in a high-speed ramming of Philippine vessels and even brandished axes and used knives to damage Philippine naval assets and puncture their inflatable vessels—severely injuring one Philippine sailor.

Such a clear display of aggression was, until recently, unexpected and uncharacteristic in China’s established pattern of gray-zone provocations.

Also alarming was the movement of a large amphibious warship (Type 075) with Chinese marines and helicopters onboard to nearby Sabina Shoal—only 36 miles away. Beijing’s increased appetite for risk should inform thinking about its willingness to act against Taiwan.

U.S. and allied responses to Chinese provocations in the South China Sea certainly inform Beijing’s broader strategic calculus.

Beijing’s recent South China Sea activity remains a subject of debate among analysts. However, a critical possibility is often left unconsidered: China is probing to test the limits of U.S. support while refining potential operational responses to a future confrontation.

That would explain why China intentionally targets the Philippines, the only country with maritime disputes in Southeast Asia that shares a mutual defense treaty with the U.S. Insight gained from these frequent provocations would likely inform Chinese assessments of how the U.S. might respond in the early stages of a kinetic conflict—including over Taiwan.

Beijing is becoming increasingly brazen within the waters it claims as its own. The departures from what were already unsettling “norms” should worry U.S. policymakers. China shows no sign of making peace in the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea.

Given Xi’s penchant for using the PLA to send geopolitical signals and influence events overseas, several impending milestones are fast approaching.

Rim of the Pacific, a major international maritime warfare exercise, will run from now until Aug. 1 with numerous at-sea drills in the waters around Hawaii. Of course, China is also watching America’s November elections.

Given these upcoming opportunities and historical precedents, China is likely to push the envelope even harder and test American resolve more directly. Unless Washington matches diplomatic words with military action and prioritizes the region, Beijing has no reason to slow down.