Fact Check: Is Climate Change Really Causing More Frequent or More Severe Hurricanes?

Virginia Allen /

Every year at this time, when hurricane season rolls around, corporate media start pumping out headlines linking the severity of hurricanes to climate change. But is there causation or correlation? And if changes in the climate do affect hurricanes, is it in the way climate activists claim?

Climatologist David Legates says, “[If] we have colder periods, we will get more hurricane activity. If we have warmer periods, the hurricane activity tends to drop off.”

Legates serves as a visiting fellow for the Science Advisory Committee in the Center for Energy, Climate, and Environment at The Heritage Foundation, and is a professor emeritus at the University of Delaware. He is also the co-author of the book “Climate and Energy: The Case for Realism.”

Legates joins “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss what connection does exist between hurricanes and a changing climate.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Virginia Allen: It’s my privilege today to welcome back to the Daily Signal Podcast, climate expert and Professor David Legates. Thank you so much for being back with us.

David Legates: It’s a pleasure to be back. Thank you.

Allen: Well, I’m excited to talk about hurricane season and climate change. I was looking at some of the big headlines because it always feels like this time of year we start hearing a lot in the news about the connection between climate change and hurricanes. Hurricane season technically starts at the beginning of June, runs through November. So this was a headline from NPR last March. They say “Sequential Hurricanes Are Becoming More Common Because of Climate Change. A CNN headline from April in 2022 reads “The Climate Crisis is Supercharging Rainfall in Hurricanes, Scientists Report. NBC News just recently ran a headline, “Category 6? Climate Boosted Hurricanes Pushed Scientists to Rethink Classifications.”

Professor Ligates are hurricanes over the past five to 10 years more severe than hurricanes were maybe 50 or 100 years ago?

Legates: Of course they are because these sites could never tell you anything that can’t be true. See, when you say more severe, we can parse that in a variety of ways. We can say there’s more hurricanes happening.

We can say that the hurricanes that happen are becoming more intense. We can say that the hurricanes that are happening are actually becoming larger and more powerful overall. Or we can say that they’re making landfall more often than not. And after all, landfall, hurricane is the worst case scenario. If a big hurricane stays out in the Atlantic, that’s only a good thing unless you’re a shipper. So we can look through each one of these in steps and I’ll give you some slides that you can see.

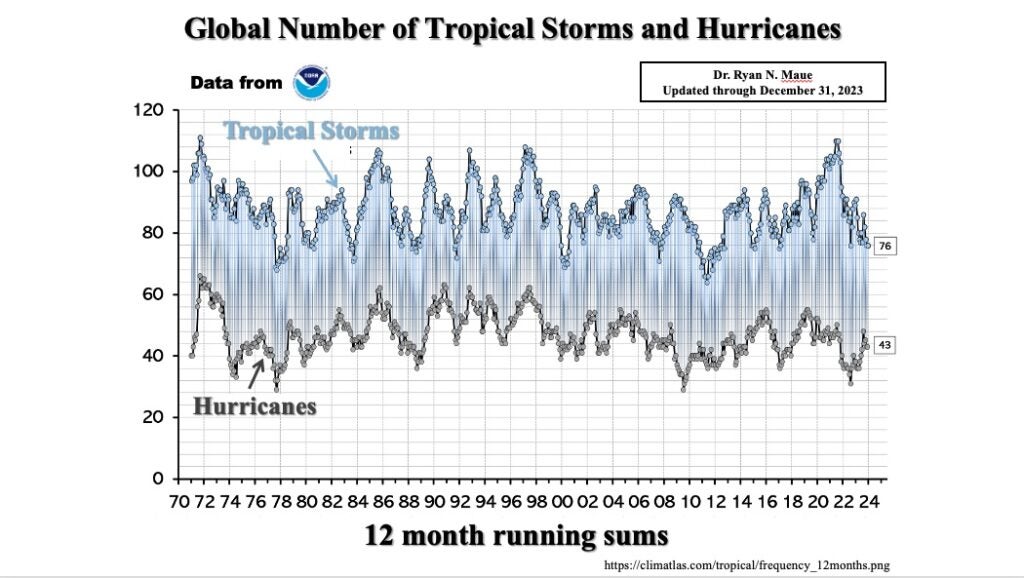

This [the below image] is by Ryan Maue. He and I worked at NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] together. He was the NOAA’s chief scientist and he’s put this together from data from NOAA. And if you look at from 1971 when we really started to be able to see things by satellites, because a lot of the Central Atlantic was missing, if you will, when we didn’t have satellites to see out there on a regular basis, ships tend not to want to sail through tropical storms and hurricanes.

As you can imagine, if you look at that record, you see lots of variability over the years, but you see no long-term trend either in tropical storms or hurricanes. So we can’t really say that over the last 50 years that there’s been a dramatic increase in the number of tropical storms or hurricanes or has there been a drastic decrease. It looks just like there’s lots of variability, which we call year to year. Some years we get hit and some years we don’t. And so there’s no change there.

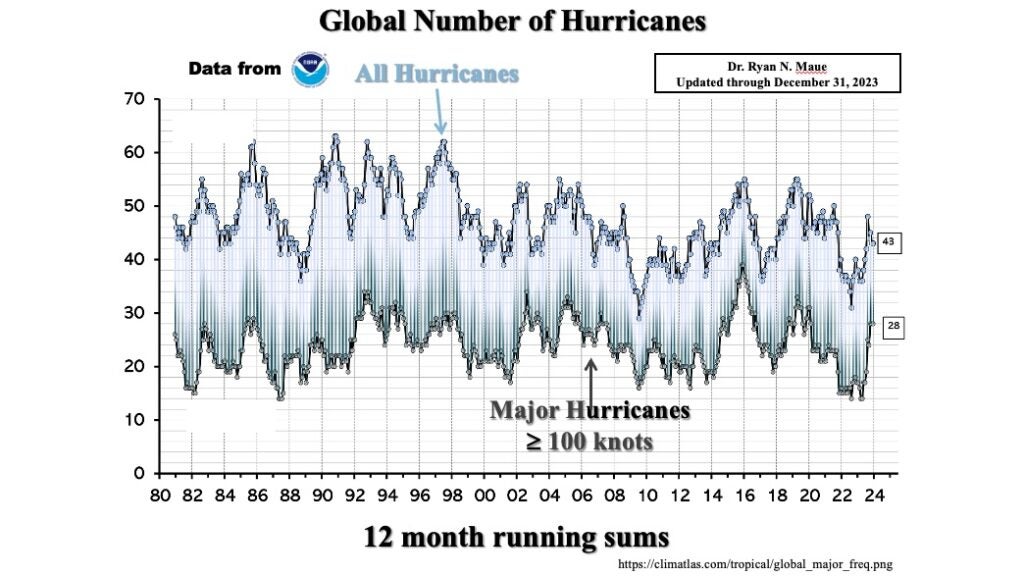

Well, maybe the ones that are occurring are becoming more intense. So we can also look at what we call major hurricanes. These are hurricanes with wind speeds that exceed a hundred knots. And when we look at that compared to all hurricanes, again, we see lots of variability but no long-term trend.

And in fact, if we look at the record closely, about a year or so ago, we were at an all-time low in terms of major hurricanes on the planet, which is kind of interesting if you are told constantly we’re seeing more of these are becoming bigger, you would expect more major hurricanes, not much less. The third argument is, well, maybe we have the same number and the same intensity, but they’re getting bigger in size, hence they’ve got more energy. And we measure that through something called the accumulated cyclone energy index or ACE index.

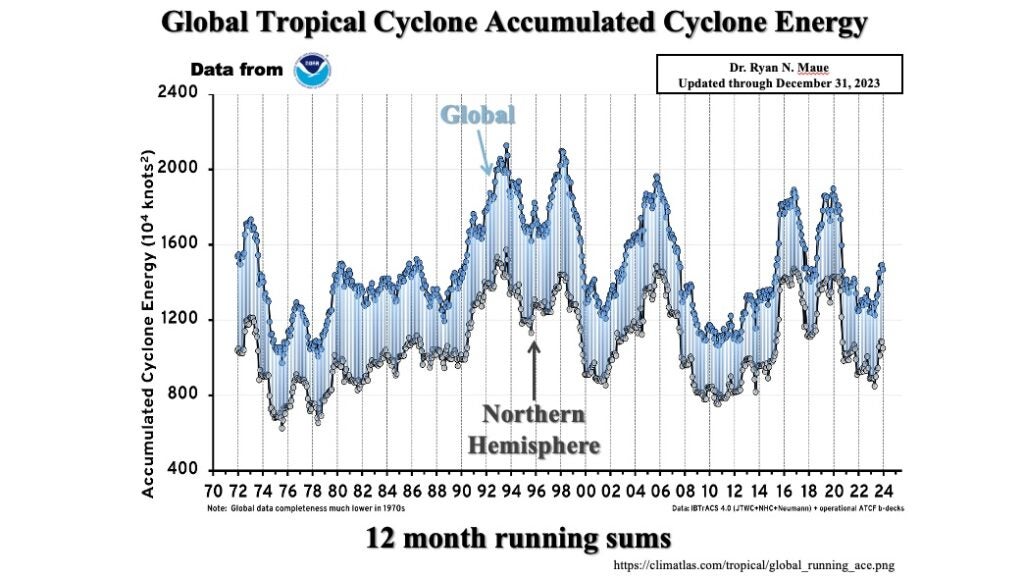

And what that does is just takes all the energy of all the storms based upon their size and their wind speed, averages them together, comes up with an index, and we look at time changes. And if you look at that from, again, from about 1972 to present over about 50 years, you see lots of variability. You see the mid nineties had lots of ACE, if you will. There was a lot of energy. It peaked again in the mid aughts or whatever we call those and peaks again in the late teens. But there is no long-term trend. It goes up and down and up and down and up and down, but never trends in either direction.

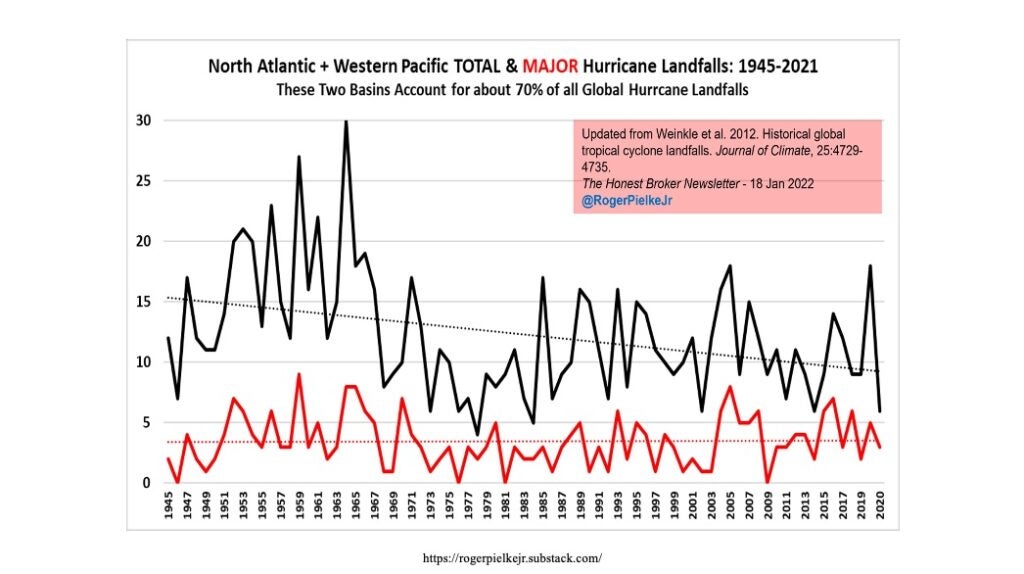

The final one that I postulated was maybe we’re seeing more land falling hurricanes. And the interesting thing is this is the first signal we actually see it’s data from Roger Pike Jr.

Looking at total North Atlantic and Western Pacific Hurricane Landfalls from 1945 to 1921. And when you look at total hurricane landfalls, they’re actually decreasing, which says in a sense that hurricanes are staying away from the coast more.

There is a lot of activity of landfall in hurricanes in the 1950s and early 1960s, which was an active period. But there’s your trend, and so if you have anything you want to write home about, it’s that landfall hurricanes are decreasing in intensity or decreasing in number over the last 50 years, which is quite opposite to what you saw on CNN and New York Times and Washington Post, all those.

Allen: So we’re seeing a decrease in the number that are making landfall?

Legates: Yes, it is less that are making landfall, which should be a good thing to write home about. I know news likes to say, let’s pick on the bad stuff. If it bleeds, it leads, but this is a good news to write home about that if there’s something in that signal, it’s a good signal.

Allen: That is a good signal. Now, we have spoken before on this podcast about how there’s natural cycles on the planet of warming and cooling. Do those cycles affect hurricanes?

Legates: Actually, they do. There’s been a number of studies done.

I think there was a study in 2001 by boost that looked at, looked at, yeah, land falling hurricanes going back to 1600. And in particular what that group found was from 1600 to 2000 in New England. This is Peterson, Massachusetts, Providence, Rhode Island area that from that 400 year period, the most active period was the 19th century. And I’ll ask the question rhetorically, what was the coldest period between 1600 and 2000? And the answer of course is the 19th century. Same research was done by Kerry Mock at the University of South Carolina. He did tropical cyclones impacting Charleston from 1778 to 1998.

The most active period in Charleston was the 19th century, which happened to be the coldest. And then a colleague of mine at LSU Kalu did some research in southern China, and he wrote remarkably, the two periods of typhoon strikes in Guangdong coincide with two of the coldest and driest periods in northern and central China. So the take home message here is that essentially if we have colder periods, we will get more hurricane activity.

If we have warmer periods, the hurricane activity tends to drop off. The next question you’re going to ask me is why does that happen?

Allen: Why does it happen? And the message that we hear from the media is the opposite. They say, because the planet is getting warmer, we’re seeing more hurricanes. But you say the opposite is true.

Legates: It’s exactly the opposite. Very good question.

So what happens is why do we get a hurricane? Essentially we have what we call an equator to pole temperature gradient. The equator is warm, the poles are cold, and so therefore we need to move energy from the equator to pole. We do that in three ways. We do that through the motion of the atmosphere. So we get westerlies for example, which is why our storms tend to move across the United States from west to east. We get easterlies in the tropics and easterlies in the polar region.

Second is we get oceanic circulation, so we get what are called gyres or circular types of circulation that exist in the oceans. And the third is by moving what we call latent heat, which is just a fancy way of saying evaporate water store energy, move it somewhere else, condense that moisture, get the energy back.

And hurricanes are very useful at doing that. They pick up a lot of water and a lot of energy from the tropics. They move forward and they drop it off. So the stronger the pole trade or temperature gradating you have, the more conflict you’re going to get and the more need there is to move energy forward. I often ask what drives the tornadoes?

For example, in the spring, the answer is you’ve got really cold dry air coming out of Canada and it’s colliding with really warm, moist air in the Gulf of Mexico. And so when you get these two contrasts come together, you get a lot of storminess. Imagine a world where the pole and the equator are exactly the same temperature. If they’re at exactly the same temperature, you’re not going to get that contrast. You’re not going to get the storminess, you’re not going to get hurricanes at all because there’s no reason to produce them there.

Storminess is going to be much reduced. So the argument is a warmer world would be a less stormy world because in a warmer world you warm the tropics but not much. It’s already very warm and you’ve got a lot of water. Water takes a lot of energy to warm, and so you get very little warming in the tropics, but you get lots of warming in the polar regions, the polar regions are drier, so you don’t have lots of water.

The polar regions are colder, so it’s easier to warm the temperature. Polar regions are covered with ice. You melt that ice, you release land underneath that’s darker. You absorb more energy cause more rising temperature. You have sea ice up there that covers the surface keeping literally the warmer water from the colder air, sea ice melts. You get more energy coming up from the ocean. There’s a variety of other reasons, but when the world warms the pole warms more than the equator, so the equator to pole temperature gradient decreases, you get less need for the severe storms and that includes hurricanes.

Allen: Are those temperatures the primary thing that scientists and climatologists are looking at when they’re predicting if it’s going to be a severe hurricane season or not? Or are there other factors that they’re looking at as well?

Legates: There’s other factors. The primary factor is to whether we’re heading into an El Nino event or a La Nino event, those are events where you’ve got a large pool of water in the Central Pacific Ocean that changes temperature for a variety of reasons. It could be because the ocean circulation changes, which changes the atmosphere.

It could be because the atmosphere changes driving circulation in the ocean. I’ve even seen arguments of subterranean magma flows affecting the ocean, which in turn affects the atmosphere.

The idea though is that climate is a mix of all of the above. And so what happens is, even though we’re talking way out in the Central Pacific Ocean, that can set up atmospheric circulation patterns that affect the formation of hurricanes, particularly even in the Atlantic Ocean Basin. So it’s what we call teleconnections that something happening halfway across the planet actually can affect something over here on the East coast.

Allen: What about this season? Do you know what we’re looking at as far as hurricane season this year?

Legates: What we’re looking at this year in particular is a very active season. National Oceanic and atmospheric administration through the National Weather Service produces a forecast. Colorado State University produces forecast as well. Colorado State’s forecast is for 11 named storms.

What we mean by a named storm is a storm that becomes a tropical storm reaches speeds of at least I think it’s 35 mile an hour, and therefore gets a name as opposed to just a number that they’re likely to become 11 named storms as hurricanes. Five forecasts become major hurricanes, which are category three with sustained wind speeds of 111 mile an hour or greater, and a fairly high, what we call accumulated cyclone energy index.

So it’s looking to be a fairly active season. The two things you really want to look for is warm water, which we almost always have enough of to create some, but it’s also wind shear is why the first prerogative is an La Nina event because La Nina tends to cut down on the wind shear.

If you think of a hurricane, it’s like a chimney. You start the rising motion and you want it to go all the way straight up to get it to form. If you’ve got what’s called a lot of wind shear, this is winds moving at different directions and different speeds at different elevations in the atmosphere.

As this chimney starts to form, it literally gets ripped apart, so winds, shear cuts back onto hurricane formation. And so even though you’ve got lots of warm water around, you may not get many hurricanes because of wind shear. This year, the wind shear is supposed to be low, which allows the formation of these towers, and therefore we expect more hurricanes.

Allen: I was talking to one of my colleagues here at The Daily Signal about this topic of what the press is saying about hurricane season and the connection that they claim connected to climate change. And one of the, that he was curious about is do we think that there is maybe more of a focus on the severity of hurricanes now simply because we have more infrastructure, so there is more to be destroyed than there was maybe 50 or a hundred years ago. Do you think that that’s part of it, that there’s maybe a heightened awareness of hurricanes simply because we have more houses, we have more businesses, we have more electrical lines now?

Legates: Exactly. More people living near the coast puts more people at risk. When you have a hurricane that makes a landfall, it’s always going to make top news, and that’s the perfect time to bring out the fact that hurricanes are related to climate change. And see, we told you all about climate change, and this is yet more proof.

I mean, one of the things I’ve been teaching at a university since 1988, I was at the University of Oklahoma, and then I went to LSU and the heart of hurricane landfall area, and there were two things that I said. One was that particularly along the East coast, it’s very difficult to get a hurricane to landfall in the Mid-Atlantic. The reason for that is it either makes landfall at Cape Hatteras because they tend to do that big sea motion where they’re coming in from the easterlies and then moving into Westerlies, so it’s like a big “C” in the ocean, letter “C,” but if you miss Hatteras, the next thing you’re likely to hit is Long Island.

So, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, they’re all sort of set back and set in, so they’re protected.

Doesn’t mean they can’t be hit, and at some point there will become a storm. It’ll go up the coast, it’ll become caught up in something happening in middle attitudes. It’ll make a left turn and come in, and of course, that storm was Hurricane Sandy. It did just that. Well, when that happens, aha, we’ve never seen this before. It’s a rare event. It must be climate change induced. Of course it wasn’t. It’s just the roll of the die, if you will. One of them is going to get caught up that way. It’s going to happen and it happens. I mean, the same thing I was talking about in Oklahoma regarding Southern Louisiana, that at some point there will be a storm. It’ll come in somewhere around Eastern New Orleans.

It’ll move up. It’ll be a past New Orleans, but its winds will be coming, wrapping around. It will hit Lake Pontchartrain. And Lake Pontchartrain, if you know anything about it, is a small shallow lake and it will be sloshed up quite a bit by the high winds and it will push up against the levees, and at some point those levees are going to give way and New Orleans is going to be flooded. But this is going to be a different flood because usually when we have coastal landfalls with the storm surge, the storm surge comes in, floods the land, the storm moves on, the surge pulls back out to sea, the land is exposed again, and you can start to rebuild.

New Orleans has been sinking over time through compaction of sediments and the building of these levees so that you never get flooding, you never get a replenishment of sediments, and they’ve all compacted over time.

New Orleans, much of it is below sea level since it’s below sea level. When the levees break, this water from Lake Pontchartrain is going to flood New Orleans, but there’s no way to get that water out. Usually rainfall is pumped out of town by a series of pumps in New Orleans, but they’re going to be underwater, so they won’t be functional, and that water’s not going to recede because it’s moved into low lying area.

So it’s just going to sit there and we’re going to have to come up with a way therefore to fix the levees so you can pump the water out so we can get back to normal, which is going to be anything but normal because the people’s lives are going to be disrupted, not just by the storm, but by the continuing aftermath. I said it would happen, and unfortunately it did not because it was a rare event, not because climate change caused it, because you knew from a physics standpoint, that’s what was going to happen at some point, and it happened sooner than later.

Allen: Is there anything that scientists, that climatologists know of that human beings can do to affect hurricanes and how severe they are? Or is this just completely out of our control as far as at least science has taken us so far.

People have always said, why don’t they just drop a nuclear bomb into one of these? You would blow it apart. And we would just, before it’s making landfall, and I’m thinking, OK, this person has no idea what a nuclear bomb does.

First of all, a storm of most magnitudes that you’re going to be willing to work against has far more energy than a nuclear bomb. Secondly, a nuclear bomb puts away a lot of fallout. The last thing you want is nuclear fallout being spread everywhere by a moving storm. Third, a nuclear bomb generally creates rising air motions, which only feeds the storm. It’s all in the wrong direction. It’s the last thing you want to do, but I get it. People want to say, we’ve got technology. We should be able to stop this. We should be able to come up with something to cause it to not happen. A warmer world might do that because as we’ve seen the coldest period of the last 400 years, the hurricanes were a little more intense. So maybe a warmer world is the best thing we could hope for.

Allen: Professor Legates, thank you.

Legates: Thank you. It was fun.